Thanks to Instagram, there’s a Buddhist Temple in Taichung that has become quite popular in recent years on, thanks mostly to the clever positioning of a street light, and the eyes of a massive Buddha statue.

Located a relatively short distance from the Taichung Railway Station and Taichung Park, like most people, having seen these photos often showing up in my feed, I figured the temple was likely a pretty popular tourist attraction, at least for Taiwanese Instagrammers, but I was surprised to learn that most people don’t even bother going inside!

Looking into the temple, I noticed something quite special about it.

Not only was there a giant Buddha statue, but there was also a Japanese-era brick temple located within the temple grounds, which peaked my interest. The historic temple, which has since been ‘protected’ by a massive Chiang Kai Shek Memorial Hall-esque building, constructed around its perimeter, was a special one given that there weren’t so many Buddhist temples constructed during that period of Taiwan’s history in this particular style of design.

So, with some time in Taichung, I decided to hop on a Youbike and ride over to check it out. Arriving at the temple, I found it strange that despite its popularity, only myself and another tourist from Japan were walking around. It was the weekend, so it was a bit odd that there were so few visitors. I did notice, though, that there was quite a bit of construction taking place on the temple grounds, with several very large, and empty-looking buildings, which appeared as if they had just been recently completed, while others were still under construction or being restored.At the time, I figured that might have something to do with with the lack of visitors.

As is the case when I visit (larger) Buddhist temples in Taiwan, I couldn’t help scratch my head at the ‘excessive’ nature of some of the buildings that were being constructed. At its heart, the Buddhist philosophy stresses the impermanent nature of all things, and that detachment from worldly possessions is one of the key elements to living a content life, but I’ve become accustomed to the fact that Taiwanese-style Buddhism tends to completely disregard these kinds of things.

If you’ve seen photos of this particular giant Buddha in the past, you’ll likely remember that it was painted gold, however, on my visit, the statue had also appeared to have undergone some reparations, and the ‘golden’ paint that covered it was removed, and was now matching the color scheme of the newer buildings that have been constructed on site, which were both massive in scale, and the amount of money it would have taken to construct them!

My interest in visiting, obviously, stemmed from the fact that the temple originated during the Japanese-era, and because there were a number of well-preserved objects that dated back to that period of Taiwan’s history. That being said, the entire time I was there, the vibe was a bit off, but I couldn’t quite figure out why. This time, it wasn’t the displays of wealth, it was something that I couldn’t quite put my finger on, and it was only until I returned home and started doing research for this article did I actually figured it out.

When I started searching for information in order to write this article, I found it odd that there was very little available about it’s history, except from the bare minimum ‘one paragraph’ kind of introduction you get from Taiwanese travel websites and none of my go-to resources had much, if anything, available.

I also found it odd that the Japanese-era portion of the temple, which has been both protected and preserved by the organization that runs the temple hasn’t received ‘official historic preservation’ status from either the Taichung City Government nor from the national government. Typically, for places like this, especially those that have such a long history, and are religious in nature, that kind of recognition is quite common.

Then, after a few frustrating hours of research, it suddenly dawned upon me what was going on, which is something I really should have picked up much sooner than I did, but I guess I was just having one of those days.

You see, prior to the Japanese era starting in Taiwan, Japan went through a political revolution known as the ‘Meiji Restoration’ (明治維新), which brought about a transformation in the country’s political and social structure. In most cases, at least in modern history, when a developing nation seeks to modernize and develop itself into a major superpower, one of the first things to get left behind would have been its monarchy, but in Japan, the ‘restoration’ was quite different in that it referred to the return of the emperor’s complete authority, which had been usurped by the shoguns.

Of all the changes that were taking place in Japan at the time, one that doesn’t usually receive much attention was the forced separation of Buddhism from Shinto places of worship. Known in Japan as ‘Shinbutsu Bunri’ (神仏分離 / しんぶつぶんり), the separation policy ended the thousand year syncretic relationship between the two religions. Despite being ingrained within Japanese culture, when the restoration took place, Buddhism was regarded as a foreign influence, whereas Shintoism would become one of the vehicles for the promotion of Japanese nationalism.

The separation originally meant to eradicate Buddhism in Japan, but that is something which ultimately failed. Where it was successful, though, is that the roles of the two religions became more clearly defined, and although Shinto was regarded as something that should be a part of daily life, Buddhism, on the other hand maintained its role as an essential means for which the people of Japan would memorialize their loved ones, acting as the vessel for funerals, graves and ancestral rites.

With that in mind, one of the main reasons why I felt like the vibes during my visit were a bit strange, and also why there’s very little information available about the temple, is simply due to the fact that from the Japanese-era until now, it has been an important place for holding funerals, and from what I’ve seen, it’s one of the most expensive venues in central Taiwan.

Today, I’ll try my best to introduce the history of Taichung’s Paochueh Temple, but I should add that I’m going to focus the most on the historic Japanese-era part of the temple rather than spending much time on the services that it offers to the bereaved. I’ll detail the history and the architectural design, and in the end, if you still feel like visiting, there will be information about how to get there!

Hogaku-ji (寶覺寺 / ほうがくじ)

Briefly touching on the events that took place during the Meiji Revolution earlier, what I didn’t really explain were the hardships that Buddhists had to face, and the ultimate evolution that the religion had to go through in order to ensure its survival in such a climate.

The purpose of the revolution was meant to modernize Japan, and the reforms pushed by the government focused on aspects of Japanese society that were deemed to be ‘feudalistic’ as well as ‘foreign.’ This brought about not only the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate (徳川幕府), but the daimyo (大名), and the samurai classes, as well, all of which were considered a burden on the state, despite their cultural and historic importance.

This is a part of Japanese history that has been well-documented in that there have been books, films, television shows and anime that help people around the world better understand the changes that the nation underwent in the late nineteenth century. What doesn’t often get mentioned, though, is that Buddhism, which was the most widely practiced religion at the time, was also targeted, and replaced by Shinto as the state religion - all in an attempt to cultivate Japanese nationalism, the notion of Japanese cultural superiority, and most importantly the idea that the emperor was divine.

In areas where Shinto Shrines and Buddhist temples were once located together sharing the same space, Buddhists faced forced eviction, with temples, often hundreds, if not more than a thousand years old, left abandoned. Similarly, many monks and nuns across Japan were left homeless, with only the larger sects able to cope with the changes.

Link: Usa Grand Shrine (宇佐神宮) - I expand more on the forced separation of Shinto and Buddhism in this introduction to one of Japan’s most important shrines.

Making matters worse, many of the larger Buddhist sects were once closely linked with the former feudalistic social system, and for centuries enjoyed the perks of being under the patronage of the samurai class. This meant that in order to survive, Buddhism had to quickly adapt to the new social order or face destruction. Thus, modifications were made by the various schools of Buddhism, which altered the core approaches and interpretations of the Buddha’s teachings to coincide with an unquestioning support for the Japanese government, its policies, and the divinity of the Emperor.

This new alignment with the Japanese government allowed for Buddhism to survive, but it also meant that Buddhism was forced to abandon some of its key principles and practices to assist in the promotion of nationalism, and ultimately militarism as well. However, even though concessions were made to conform to state ideology, the forced separation of temples and shrines ultimately resulted in the closure or destruction of over 4,500 Buddhist temples across Japan. Similarly, monks and nuns were either drafted into the Imperial army, or forced to return to ordinary life, depending on their age.

It should be noted, though, that although Buddhism underwent modifications in order to survive, what didn’t really change is that a large portion of the population continued to follow and support the religion, and even high-ranking members of the government took issue with what was going on.

With all of that in mind, it’s somewhat surprising that when the Japanese arrived here in Taiwan, Buddhism was something that helped bridge the cultural gap between the locals and their new colonial ruler. Japanese monks were sent over with military regiments in order to provide spiritual service to the army, but they served as medical practitioners and educators, as well, and as the army made its way around the island, the monks were also able to perform missionary-like services. Suffice to say, the work that Buddhist monks did in the early years of the colonial era earned them political support from Taiwan’s Governor Generals, who in turn allowed Japan’s major Buddhist sects to came to Taiwan to propagate their teachings while also continuing to serve a myriad of roles within the public space.

Throughout the half-century of Japanese rule, the Kegon (華厳宗), Tendai (天台宗), Shingon (真言宗), Rinzai (臨済宗), Soto (曹洞宗), Jodo (浄土宗), Nichiren (日蓮宗), and several other schools of Buddhism were active in Taiwan. Similar to the hierarchical system in Japan, each of these sects would become associated with a central regional temple in Taiwan, known as the ‘Four Holy Mountains’ (台灣四大名山), which were set up to represent the four cardinal directions of north, east, south, and west.

The (original) Four Holy Mountains are as follows:

Yue-Mei Mountain (月眉山派) in Keelung, associated with the Soto Sect (曹洞宗).

Kuanyin Mountain (觀音山派) in Taipei, associated with the Rinzai Sect (臨済宗).

Fayun Temple (法雲寺派) in Miaoli, associated with the Soto Sect (曹洞宗).

Dagang Mountain (大崗山派) in Kaohsiung, associated with the Rinzai Sect (臨済宗).

Note: Coincidentally, when the Japanese-era came to an end, this system remained relatively the same with the Rinzai and Soto sects remaining, but in this case, the Four Holy Mountains are currently, Fo Guang Mountain (佛光山), Dharma Drum Mountain (法鼓山) and Chung Tai Mountain (中台山), which kept (a loose) association with the Rinzai and Soto schools, while the fourth, Tzu Chi (慈濟) is somewhat of a mixture of Buddhist schools and beliefs.

In each case, these organizations have grown exponentially, and although they are representative of Taiwan’s ‘Humanistic’ (人間佛教) approach to Buddhist philosophy - ‘promoting social engagement and involvement with society, modernizing Buddhist teachings, and focusing on issues of environmental protection, human rights and wildlife conservation’ - they also command massive wealth and political power, which is something that they’re often criticized for.

What you’re likely to have noticed is that both the Rinzai and Soto schools, during both the Japanese-era and the modern era, have remained the two more prominent schools of Buddhism in Taiwan, but that isn’t something that should be too surprising, given that both of these schools of ‘Zen Buddhism’ (禪宗) originated in China, and are simply considered to be the Japanese lineage of a much older school of Buddhism.

Despite Buddhist monks having been active in Taiwan since 1895, when the Japanese first arrived on the island, it took at least five years for the first temple to appear. In 1900 (明治33年), Governor General Kodama Gentaro (兒玉源太郎) made an official request for the monks who were active in Taiwan to start construction on a temple as well as being given official permission to promote of Japanese Buddhism in Taiwan.

Whether or not the Governor General himself was a Buddhist is open for debate, but what’s important to note is that he was sent to Taiwan during a period of social and political turmoil, and the living conditions for people on the island were considerably difficult. Kodama was of the opinion that the power of religion could help to stabilize society, and since Buddhism was more well-established with the locals than Shinto was, Japanese monks were able to find a new home in Taiwan, which, ironically was probably a far more friendlier place than the Japanese mainland.

For the Rinzai School (臨済宗 / りんざいしゅう) in particular, construction on the Chin'nanzan Gokoku-ji Temple (鎮南山護國禪寺), which is located next to Yuanshan MRT Station (圓山捷運站) in Taipei, was completed in 1911 (明治44年), and would act as the headquarters for the a number of their temples across Taiwan. One of those temples in its network would be ‘Hogaku-ji’ (宝覚寺), or ‘Paochueh Temple’ as it is known today. Established in Taichu Prefecture (台中州) in 1928 (昭和3年), with temple acting as central Taiwan’s Myoshin-ji (妙心寺 / みょうしんじ) branch.

Note: I realize, for anyone not particularly familiar with Japanese Buddhism, I just threw out a lot of terms. Rinzai is essentially just one of the largest Buddhist lineages in Japan, and it’s split into about fifteen different branches. Each of the branches is purely based off of a head-temple, and not particularly that they have different beliefs of practices. The Myoshin Branch, which is headquartered in Kyoto, just so happens to be the largest and most well-known of the branches.

Hogaku-ji was established by Gisei Higashiumi (東海宜誠禪師), a monk who was known for completely devoting himself to Taiwan, and learning the Taiwanese language in order to better serve the people here. The newly constructed temple wasn’t just an important place of worship, but also featured a Buddhist academy, and a kindergarten for local children.

Official literature points out that the first abbot of the temple was known as the ‘Art Monk’ (藝僧), but that doesn’t really explain very much given the special circumstances of who this person actually was. It took me a big of digging, but I was quite surprised to learn the first abbot of the temple, was a locally born Hakka monk. Born as Chang Miao-Chan (張妙禪) to a well-off family in Hsinchu’s Beipu township, at a young age, he was afforded the opportunity to learn how to play the piano and chess and was skilled at calligraphy, painting and various sculpture techniques, which is where his ‘Art Monk’ nickname would eventually be derived.

Rising to prominence for his work at the Rinzai temples on Shitoushan (獅頭山), a short distance away from his home in Beipu, at the time, this sort of a promotion for a local Formosan citizen would have been pretty rare. However, with the influence of Taiwanese-speaking Gisei Gigashiumi and the Chinese and Hakka-speaking Chang Miaochan, the two monks worked hand-in-hand to promote education in Taiwan through the Rinzai sect’s Chin’nan Academy (鎮南學林), and since the newly established Hogaku Temple in Taichung also served as a Buddhist academy, he was the perfect choice to act as the head abbot.

Keeping in mind what I mentioned above with regard to the ‘Four Holy Mountains’, the idea of a ‘mountain’ (山) in both Chinese and Japanese Buddhist traditions is a special one. In both languages, the ‘mountain’ speaks to the temple’s affiliation. In Japanese, the term ‘sangou’ (山號 / さんごう) is used when referring to the name of a temple. The ‘sangou’ always appears before the name of the temple, similar to how the different denominations of Christianity give titles to their churches, but in this case it just helps people better understand the association.

This, however, is an area of my research for this temple that has been quite frustrating. In the official literature, there are two of these ‘sangou’ listed, and for some reason the few resources available insist that they were both used during the Japanese-era.

Thus, the temple has (apparently) had the following names:

Juheizan Hogaku-ji (鷲屏山寶覺禪寺 / じゅへいざんほうがくじ)

Shobozan Hogaku-ji (正法山寶覺禪寺 / わしへいざんほうがくじ)

In the case of the latter, ‘Shobozan’ (しょうぼうざん), it’s a common ‘sangou’ used to mark an affiliation with the Myoshin sect of the Rinzai School, so it shouldn’t be surprising to see that this name would be used to demarcate the temple. Where I got really confused, though, was with the other name. The issue was that there isn’t actually a mountain titled ‘Juheizan’ (鷲屏山), and even more confusing is that the pronunciation of the first character in the word is most often pronounced ‘washi’ (わし), which refers to an eagle, among other things. It took a while, but I eventually put two and two together to figure out that they were actually referring to the ‘Vultures Peak,’ a prominent location in the stories of the life of the Buddha.

The peak, which is known as ‘Gridhrakuta’ in Sanskrit, is most often referred to as ‘Ryo-zen’ (霊鷲山 / りょうじゅせん) in Japanese, referring to the ‘Vulture’s Peak’ where the Buddha would often bring his disciples for training and retreat. This is something that is often mentioned in Buddhist sutras and the koans used by practitioners of Rinzai. Similarly, if we keep in mind the name of the temple, ‘Hogaku’ (寶覺 / ほうかく) which translates to the ‘awakening’ (or the enlightenment) of the Buddha, its probably not too difficult to see why it would be used, with the temple acting as both a place of worship and of learning. That being said, I couldn’t find any other Buddhist places of worship with this ‘sangou’, so if it was, in fact, the title used for this temple, it was likely that it was unique.

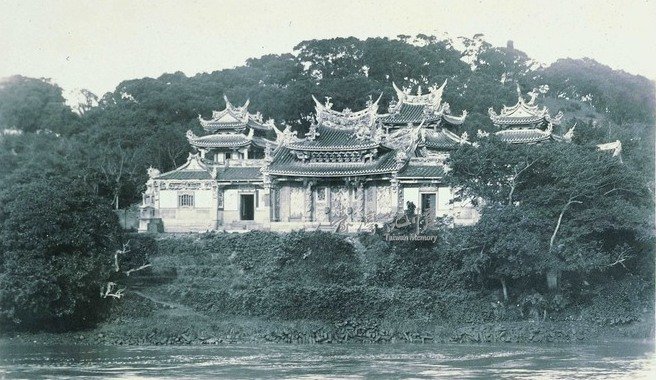

When Taiwan’s Japanese-era came to an end with the empire’s surrender at the end of the Second World War, Hokgaku Temple became known as ‘Paochueh Temple,’ which was just a simple change to the Mandarin pronunciation of the original name. That, however, was just a minor change compared to everything else that would take place over the next several decades. From the historic photos that I’ve seen of the temple, there were actually quite a few interesting buildings constructed on the grounds, including a beautiful seven-layered pagoda, a school building, dormitories for the monks, a bell tower, in addition to a large courtyard with a considerable amount of nature, including trees, ponds, etc. Essentially, the layout of the temple followed what is known as the ‘Shichido garan’ (伽藍 / がらん) style of design, which essentially just means that it featured what the Japanese referred to as a ‘complete temple complex.’

At first, not much changed, but as the decades passed, a number of the original buildings were torn down to make way for newer, much larger buildings, a giant cement statue of the Laughing Buddha was added, and most of the trees were removed, and eventually a wall was erected around the complex.

Sadly, the seven-layered pagoda (in the photo above) that once stood on the western side of the grounds was removed, and replaced with a much larger, much more posh building for funerary services. Similarly, the bell tower, the school, and the dorms were all torn down. Architecturally speaking, the loss of these buildings, at least as far as I’m concerned, is quite unfortunate, because they were all constructed with Showa-era architecture, and from the photos I’ve seen of them, there aren’t many buildings like them left standing in Taiwan today.

Obviously, one of the more significant changes came in the 1970s when the temple’s 100 foot tall Buddha was constructed. I’ll spend more time introducing the statue a bit later, but as you might imagine, the addition of such a large statue within the heart of the city made the temple a popular tourist attraction once it was completed.

With all of the expansion that has taken place over the seven decades since the Japanese left Taiwan, the temple has transformed from a beautiful natural space within the heart of the city to a large cement shadow of its former self. That being said, with all of the modernization taking place, efforts have been made to preserve important parts of its history, which is admirable, because the loss of the original temple would have been a shame.

One of the admirable aspects about the temple that doesn’t really get mentioned too often, is that even though the Japanese gave up control of Taiwan decades ago, the close links and associations between Taiwan and Japan have remained strong. As I mentioned earlier, it’s important to note that the temple was originally a place where the Japanese would hold funerals as that was something that Shinto Shrines don’t actually take care of. So, even though the Japanese left, the Japanese and Taiwanese citizens who were interred within were never moved. In order to allow for the families of the deceased to be able to pay their respects, former Governor General of Taiwan, Kiyoshi Hasegawa (長谷川清/はせがわきよし) visited the country in 1957 in order to assist in the organization of ossuaries for deceased Japanese nationals at Buddhist temples across Taiwan.

To this day, Paochueh Temple remains home to one of these ossuaries, and every year a ceremony is held to honor the dead.

The friendship that the temple has shown to Japan has also been of benefit as the Japanese Buddhist Association (全日本佛教會) has donated several generous gifts over the years, while the organization that runs the temple today also maintains its links to the Myoshin Rinzai sect.

Before I move on to detailing what you’ll see when you visit the temple, I’ve put together a condensed timeline of events in the drop down box below with regard to its history, for anyone who is interested:

-

1895 (明治28年) - The Japanese take control of Taiwan as per the terms of China’s surrender in the Sino-Japanese War.

1911 (明治44年) - The Myoshin Rinzai Chin'nanzan Gokoku-ji Temple (鎮南山護國禪寺) is completed in Taipei

1928 (昭和3年) - Hogaku Temple is established in Taichu Prefecture by monk Gisei Higashiumi (東海宜誠禪師) on a large plot of land to the west of the downtown core of Taichu City.

1929 (昭和4年) - Taiwan-born Hakka monk, Chang Miao-Chan (張妙禪), also known as the ‘Art Monk’ (藝僧) is appointed the temple’s first abbot, and a Buddhist academy and a kindergarten open on the grounds.

1954 (民國43年) - The Japanese Buddhist Association (全日本佛教會) donates a statue, known as the “Peace Buddha” (和平觀音) to the temple.

1957 (民國47年) - Former Governor General of Taiwan, Kiyoshi Hasegawa (長谷川清/はせがわきよし) helps to organize ossuaries for deceased Japanese citizens in several locations across Taiwan. The ossuary (日本人遺骨安置所) in central Taiwan is located within the temple grounds, and every year a ceremony is held to honor the memory of both the Japanese and Taiwanese citizens memorialized within.

1964 (民國53年) - Construction on a giant cement statue of the Laughing Buddha gets underway with more than two million dollars raised in funds from local businesses and citizens.

1973 (民國62年) - An eight foot fall statue of Jizo (地蔵菩薩 /じぞうぼさつ) is donated to the temple by the Myoshin Temple in Japan.

1975 (民國64年) - The statue of the Laughing Buddha is completed.

1987 (民國76年) - Due to the theft of the temple’s property over the years, the temple undergoes a period of renovation with a giant front gate and a wall that surrounds the complex added for security. It was also during this time that the ‘Folklore Museum’ (民俗文物館) within the interior of the Buddha statue was converted into a library and a filial piety education hall.

1990 (民國79年) - For some odd reason, the giant Buddha statue is painted gold.

2008 (民國97年) - A monument with a Haiku by famed Japanese poet Haneda Gakusui (羽田岳水), who spent his youth studying and teaching in Taiwan was donated to the temple. The Haiku, translates literally as: “The smile of the Maitreya Buddha under the flowers of the Bodhi Tree” (在菩提樹花下彌勒佛的微笑).

2008 (民國97年) - The original temple is elevated from its original position and a completely new massive bell tower-like structure is constructed around it.

Architectural Design

Most of the time when I get to the architectural design section of these articles, I do a deep dive into the specifics of the building’s design so readers can better understand what they’re seeing when they visit. This time, I’m going to be introducing a couple of different aspects of the temple that you’ll want to take note of when visiting, but for brevity, and due to a lack of resources, I’ll be offering fewer details than usual.

More specifically, I’ll be introducing the main attraction, the historic part of the temple, but I’ll also offer information about the Buddha statue, and some of the other significant objects that most people may not realize are significant.

Hall of Great Strength (大雄寶殿)

Traditionally, the Main Hall of a Buddhist Temple is known as the ‘Mahavira Hall’ (大雄寶殿 / だいゆうほうでん), but due to confusion with its name in Mandarin and Japanese, when it’s translated to English, it’s often literally translated either as the ‘Precious Hall of the Great Hero,’ or the ‘Hall of Great Strength,’ which probably aren’t the best ways to describe the building. Personally, I prefer to just refer to these buildings as the ‘Main Hall’ (正殿), because its the most important area of the temple where worship takes place, and where you’ll find statues of the Buddha.

On that point, the Buddhist figures enshrined within the ‘Main Hall’ share similarities with most of East Asia’s Buddhist temples, but when it comes to the building’s architectural design, what doesn’t get mentioned very often is that it is a fusion of Japanese, Taiwanese and Western styles of design, which makes it stand out from most of the Buddhist temples you’ll find in Taiwan today, especially those that remain from the Japanese era.

Starting with the interior, the main shrine is dedicated to the ‘Three Jewels’ (三寶佛), with the number ‘three’ being a significant one in that the cornerstones of Buddhism are the Buddha (the teacher), the Dharma (the teachings), and the Sangha (the community of practitioners). Similarly, the three Buddhist figures who make up the ‘Three Jewels’ are said to represent the ‘Buddhas of past, present, and future’ (過去未來現在諸佛), another core aspect of Buddhist philosophy.

The ‘Three Jewel’ Buddha’s enshrined within the Main Hall are as follows:

Amida Buddha (阿彌陀佛 / あみだぼさつ) - located on the left

The Buddha (释迦牟尼佛 / しゃか) - located in the center

The Medicine Buddha (藥師佛 / やくしにょらい) - located on the right

Unfortunately, the size of each of the statues, what material was used to craft them, and the year they were created is all information that is unavailable. From what we can see from the historic photos available of the shrine above, it’s possible that the statues were replaced at some point, but given the angle that the photos were taken, and the fact that they’re monochrome, it’s difficult to compare. One aspect that is more obvious, though, is that the eight foot statue of Jizo, which at one time accompanied the three Buddhas has been removed. It’s possible that it was moved to the funeral area of the shrine, but there isn’t any information as to where it was moved or why.

An important aspect of the temple that does remain, though, are the two white elephants that were originally located at the entrance. They’ve since been moved to accommodate the building’s migration, but they remain just outside the main entrance. If you’re wondering why there are two white elephant statues in Taiwan, it’s not actually out of the ordinary for Buddhist temples as the elephant is a symbolic animal for Buddhists. Elephants are renowned for their wisdom, intelligence and patience, and have long been associated with the Buddha, which is why they’re often found in Buddhist iconography.

One of the more notable aspects of the interior design of the building is the inclusion of a caisson ceiling (八卦藻井) in the middle, just above the heads of the statues. A caisson, or a ‘Bagua Ceiling’ is basically a sunken layered panel in a ceiling that raises above the rest of the ceiling almost as if there were a dome above it. The layers of a caisson are often beautifully decorated and with a design at the center. In this case, there’s a Buddhist swastika (no not that one). The most amazing thing about these ceilings are that they are designed using expertly measured interlocking pieces that connect together in a way that neither beams nor nails are used to keep them in place.

In terms of the building’s architectural and interior design, this would be what I was referring to as the ‘Taiwanese’ inclusion, but I may be letting you down by reporting that it was an addition to the temple that came well-after the its original construction. There isn’t any information available as to when it was added, but a safe guess would be that it was part of the restoration and renovation project that took place in the late 1980s.

Even though it’s not an original part of the temple, it’s still quite nice, and whenever I see one of these things, I get completely distracted by how beautiful they are.

Now onto the architectural design specifics.

The building was constructed using a Japanese style of design for Buddhist Temples, known as the ‘Drum Tower’ (樓造), or ‘korou’ (ころうぞう) design. Mimicking a bell-tower, which is often an important inclusion for larger Buddhist temples, from the exterior, the building appears to be a two-storied structure that first and foremost makes use of the ubiquitous irimoya (入母屋造 / いりもやづくり) style of design. This is a style that has a wide range of uses within Japanese-style architecture, and is used not only in Buddhist temples, but also Shinto Shrines, castles, and even in houses.

In this style of design, the roof is one of the most important aspects of the overall design, but as far as I’m concerned, the most important thing to keep in mind about buildings with this style of design is that the ‘moya’ (母屋 / もや), which is essentially just the ‘core’ of the building is constructed with a genius network of pillars and trusses both in the interior and exterior that ensures the building’s stability, but also adds an ample amount of support for the weight of the (whatever style of) ‘hip-and-gable’ roof that is chosen to cover it.

What ends up completing this style of design is that the core of the building is complimented by a roof that eclipses the size of the core, and although the roof in this case doesn’t extend that far beyond the base, the ‘bell-tower’ aspect of the design is what’s important.

Like many Japanese-style Buddhist temples, the roof was constructed as a ‘double-eave hip-and-gable style’ (重簷歇山式), and is covered with beautiful Japanese black tiles (黑瓦). Despite its comparable simplicity in design, the roof is actually quite similar to what you’ll see at the Huguo Rinzai Temple (臨濟護國禪寺) in Taipei in that it has the highest section has flat main ridge (正脊) with a four-sided hip roof that slopes down on all four sides, with two triangular gables on the eastern and western sides.

The upper eaves and the lower eaves are separated by a section of the core that has windows on all four sides of the building, and the lower eaves, another four-sided sloping roof extend well beyond the core of the building, covering what is known as the ‘hisashi' (廂 / ひさし), which is more or less like a veranda that surrounds the building and is complimented by pillars that help to stabilize the roof’s weight.

Where this temple differentiates itself from the Rinzai headquarters mentioned above is that it was constructed using the Showa-era approach to construction. While the temple in Taipei is one of the largest remaining Japanese-era temples constructed entirely of wood, this one is special in that it was, instead, constructed with reinforced concrete and Taiwan’s iconic red bricks. This kind of construction is something that became quite common in the latter stages of the Japanese-era, for both practical and decorative reasons.

The architects of the time were big fans of using this western-fusion style of design, but it was also important as a functional aspect to construction as earthquake-proofing was important for the longevity of buildings. That being said, of the Buddhist temples that remain in Taiwan today, it’s not common to see one constructed of bricks like this one, so it’s pretty special.

I’m not going to spend much time detailing the design of the newly constructed building that currently encircles the original temple. Looking at it from afar, its obvious that a considerable amount of money was spent to build it, but it’s not (currently) completely open to the public.

There isn’t much information available about what’s on the top floor of the building, but I’m assuming that since it is also bell-tower-shaped, its purpose is not only to ensure the protection of the historic temple, but also to replace the original bell tower that has since been demolished.

It’s also important to keep in mind that the temple is home to three historic bells, one known as the ‘Sanskrit Bell’ (梵鐘) donated by former Japanese Governor General of Taiwan, Hasegawa Kiyoshi (長谷川 清 / はせがわ きよし), another known as the ‘Friendship Bell’ (友愛鐘) donated by the ‘Japan-Taiwan Memorial Tower Construction Association’ (日本囯台湾物故者慰靈塔建設会), and another constructed with funds from more than a thousand Japanese citizens, with the inscription, ‘Eternal Friendship’ (友愛永傳).

In total, the three bells are likely to weigh over a thousand kilograms, so its likely that they’re being protected in the tower above. If you walk around to the rear, you’ll find a private elevator that could probably transport you to the top of the building, but you might have to ask nicely if you want to go up and see what’s there. Unfortunately, like so many other things about this temple, the lack of information makes it a bit of mystery.

Giant Buddha Statue (巨佛像)

Despite the constant stream of Japanese visitors over the years, Paochueh Temple’s status as a tourist destination was firmly ‘cemented’ in the 1970s with the addition of a massive statue of the ‘Laughing Buddha’ constructed on the grounds. Planned and constructed at a time when the Taiwanese Economic Miracle (臺灣奇蹟) was taking place, the temple successfully raised more than two million dollars in donations from local companies and citizens for the project, which would take almost a decade to complete.

When it was finally completed in 1975, the 10 foot wide, 100 foot tall cement statue became an instant hit with people from all over Taiwan visiting. This was likely a time when giant statues were few and far between, which isn’t the case these days.

Often mistaken by people in the west, the so-called ‘Laughing Buddha’ isn’t actually the progenitor of Buddhism, but instead is the likeness of the Chinese Buddhist monk, ‘Qieci’ (釋契此) who lived during the Later Liang Dynasty (後梁), around the 10th Century.

More commonly known here in Taiwan as ‘Budai’ (布袋), or in Japan as ‘Hotei’ (ほてい), he is traditionally depicted as an overweight, bald monk wearing a simple robe. As a monastic, he carries few possessions, save for his ‘cloth sack’ (布袋), which is where his name is derived. Despite having few possessions and living in poverty, he remains content and always has a smile on his face.

Within some circles in the Chinese Buddhist tradition, the image of the monk Budai has become synonymous with the ‘Maitreya Buddha’ (彌勒菩薩), or ‘The Future Buddha’, a Jesus-like figure, who it is said is the direct successor to the Buddha himself, and will appear at a time when the world needs saving.

Note: Given the ‘savior-like’ nature of the idea behind Maitreya Buddha, it shouldn’t be much of a surprise that a number of prominent cult leaders over the years have claimed that they were a reincarnation of Budai. Similarly, there are several large religious groups operating in Taiwan today that worship Maitreya, or have leaders claiming to be him, including Yiguandao (一貫道), Falun Gong (法輪功), and the Maitreya Great Tao (彌勒大道). Fortunately, in this case, you don’t have to worry about getting sucked up into any cult-like activities with regard to this statue.

When the statue was completed in 1975, its purpose was to simply help bring a smile to anyone looking at it, which would have been quite easy as the area around the temple had yet to really develop very much, making it the tallest structure in the area, dominating the skyline.

Looking at the statue, you’ll find the phrase, “Everyone is Happy!” (皆大歡喜) etched in Chinese calligraphy on the ten foot high base. Similar to the Great Buddha on Changhua’s Bagua Mountain, the interior of the statue has several floors, and has been used for a number of purposes over the years. It seems like the interior hasn’t been accessible to the public for quite a while, but when the restoration of the statue is completed, maybe it’ll reopen for visitors.

Featuring seven floors, and a large window in the Buddha’s belly, the interior space has been used as a library, with the other floors reserved as folklore galleries and exhibition spaces.

In the 1990s, for reasons that aren’t really well-documented, the statue was painted gold, and if you’ve seen photos of the statue in the past, you’re likely wondering what happened. My personal opinion on this might be divisive, but the yellowish-brown paint that coated the statue was pretty tacky, so I’m happy to see that it has been returned to its original condition during the recent restoration and expansion project that the temple has been going through, especially since the statue matches the color scheme of the other new buildings constructed inside.

Japanese Ossuary (日本人遺骨安置所)

One of the things that makes this temple quite special is something that I mentioned earlier, and also something that I’m sure quite a few people might pass by without actually realizing it.

Located near the main gate, you’ll encounter an object that has become an important bridge between the peoples of Japan and Taiwan, and something that has been part of this temple’s legacy for almost a century. For anyone unaware, an ossuary is essentially a ‘container’ for the cremated bones of the deceased, and the ossuary you’ll encounter here is dedicated to the memory of members of the Japanese armed forces, both Japanese and Formosans alike, who passed away during the fifty year colonial era.

Taiwan is currently home to three of these ossuaries, with one located in the north, another in the south in addition to this one at Paochueh Temple, dedicated to the fallen service members who resided in central Taiwan.

In front of the ossuary, you’ll find two stone lanterns, the exact same kind that you’ll encounter at a Shinto Shrine. The ossuary itself is an urn-like structure with a plaque on the front that signifies that it is for resettled Japanese remains. The ossuary isn’t very large, but it is respectfully surrounded by some well cultivated bushes, making it a bit more attractive than it would be if it were there all by itself.

The temple holds memorial services in front of the ossuary in the spring and in the autumn, which is often attended by Japanese citizens living in Taiwan, or families members who have flown over specifically for the event.

In addition to the ossuary, there has also been a stone plaque erected nearby for the benefit of the family members of Japanese citizens coming to pay their respects as well as a pavilion where you’ll find a statue of Guanyin, which is dedicated to peace.

In the first case, the Hometown Memorial Monument (靈安故鄉慰靈碑) is a large slab of stone erected on a pedestal, which has the purpose of comforting those to stand in front of it. The Peace Pavilion (和平英魂觀音亭) on the other hand is dedicated to the memory of the fallen soldiers, and the pursuit of peace in the post-war era and features a golden statue of a standing Guanyin.

Finally, just around the bushes from the ossuary, you’ll find a statue of Jizo, one of Japan’s most well-loved Buddhist figures. In Chinese, the statue’s name is literally translated as The ‘Guardian of Children Jizo Bosatsu’ (護兒地藏王菩薩), an important Buddhist figure in East Asia, who is regarded as the guardian of children and patron deity of deceased children and aborted fetuses in Japanese culture.

The inclusion of the statue here might lead one to believe that there are also the ashes of children interred within the ossuary, but given his importance within Japanese Buddhist traditions, it shouldn’t surprise anyone that he makes an appearance at the temple

Getting There

Address: #140 Jianxing Road, North District, Taichung City (臺中市北區健行路140號)

GPS: 24.159440,120.687930

Located within the heart of downtown Taichung, and walkable from Taichung Train Station, the temple is close to a number of tourist attractions, including the Taichung Confucius Temple, Taichung Martyrs Shrine, Yizhong Street Night Market, Taichung Park, etc. Getting to the temple is pretty easy given that you can simply walk from the train station, take a Youbike, or make use of Taichung’s public transportation network.

My visit coincided with a trip to Taichung Park and Taichung Train Station, so I started with a GoShare scooter ride to the temple, and when I was done, I walked to the other two. How you get there, though, is completely up to you. If you decide to walk, simply input the address provided above into the maps app on your phone and it’ll map out the best route for you to take.

As mentioned above, there are quite a few tourist spots along the way, so it could be an eventful walk.

Public Transportation

If you’re already in the city and would like to visit, the temple unfortunately isn’t accessible via the Taichung MRT, and it doesn’t look like it will be in the near future. So, if you want to make use of public transportation, Taichung has a number of buses that stop nearby.

If you weren’t already aware, due to the lack of a proper subway system in the city for so long, the bus network has become quite expansive, convenient and reliable. So, if you’re in town, taking the bus is probably one of your better options for getting around.

Admittedly, though, the network is expansive, and can be a bit intimidating for people who are unfamiliar, but that’s why Google Maps should be your best friend! Simply open up the app on your phone, set the temple as your destination, and it’ll provide you with the bus routes that you’ll need to take to get there.

Still, given that there are a number of options, I’ll list the closest to the temple and link to them below. It’s important to note that the three closest bus stops to the station could be confusing for travelers given that they have the same name, with just a slight difference. Each of the stops are named ‘Shin Ming High School’ (新民高中), but they’re differentiated by the road that they stop on. The closest stop to the temple is the Jianxing Road (健行路) stop, which is just across the street, while the other two are located a two minute walk away on Sanmin Road (三民路) and Chongde Road (崇德路).

1. Shin Ming High School (Jianxing Road)

Bus Routes: 200, 303, 304, 307, 308

2. Shin Ming High School (Sanmin Road)

Bus Routes: 8, 14, 21, 59, 203, 270, 271, 277, 900

3. Shin Ming High School (Chongde Road)

Youbike

Just outside of the temple on the sidewalk, you’ll find a large Youbike Station where you can swipe your EasyCard and hop on one of the shared bicycles. Keeping in mind that there is a large school just across the street, there are Youbike docks on both sides of the road, and other docking stations nearby as well. You shouldn’t have much difficulty finding a bike, or finding a spot to dock it when you’re done.

If you haven’t already, I highly recommend downloading the Youbike App to your phone so that you’ll have a better idea of the location where you’ll be able to find the closest docking station.

If my introduction, and all that I’ve described about its history is any indication, I’m slightly on the fence as to whether or not this temple should really be considered a ‘tourist’ destination. For a lot of locals, the fact that it’s a place where funerals are held is probably one of the reasons why they’d be prone to staying away, unless they absolutely had to visit, but over the years the temple has expanded considerably, and the inclusion of the giant Buddha statue made it a popular stop.

The Taichung City Government promotes the temple on its travel website, so I suppose its marketed as a place for people to visit when they’re in town, but it’s important for anyone visiting to keep in mind that certain areas are off-limits, and as I’m writing this, with all the construction taking place, a large portion of the grounds aren’t accessible. When everything is finished, though, I’m sure there will be more for tourists to enjoy during a visit.

Until then, it’s probably good enough to enjoy a view of the giant Buddha statue and the historic Japanese-era temple that has been so well-preserved. If you do end up visiting, I hope this introduction to the temple helps you better understand what you’re seeing.

References

Taichu Prefecture | 臺中州 中文 | 台中州 日文 (Wiki)

Linji school | 臨濟宗 中文 | 臨済宗 日文 (Wiki)

Myōshin-ji | 妙心寺 中文 | 妙心寺 日文 (Wiki)

Buddhism in Taiwan | 台灣佛教 (Wiki)

Japanese Buddhist Architecture | 日本佛教建築 中文 | 日本建築史 日文 (Wiki)

Paochueh Temple (Taichung Travel)

台中-北區 寶覺禪寺 (Just a Balcony)

寶覺寺 (台灣好廟網)

台中市北區 寶覺禪寺 (拜好廟。求好運)

寶覺寺: 在台日本人遺骨安置所 (Vocus)

日治時代的台灣佛塔建築調查研究研究成果報告 (陳清香)

日治時期高雄佛教發展與東海宜誠 (江燦騰 / 中華佛學學報)

Historic Photos (開放博物館)