The purpose of this website, and by extension this blog, has always been to showcase my photography and my travels around Taiwan. Over the years, I’ve been quite adamant that my photos should always be used to help tell the story of the places I’ve been visiting around the country. This article is thus going to be somewhat of a first for me and I’m publishing it mostly just to serve as a reference for a few of my other articles.

To start, I should offer a bit of a backstory: I don’t spend all that much time on social media, but from time to time, I find some real gems shared in the Taiwanese history groups that I follow. So while browsing recently, I came across a photo of (what appeared to be) something out of a newspaper. The photo appeared aged, and featured a list of locations in Taiwan that were part of a major name-change policy that took effect in the early 1920s.

This was something that automatically interested me, especially since it was primarily focused on the railway, so given that it was all in Chinese, I quickly translated parts of it, and shared it on my Twitter. I’m not necessarily going to suggest that the tweet went viral, but it did attract quite a bit of attention, especially from Taiwanese followers who commented that they had no idea about many of the original place names that they were seeing on the photo.

The photo appeared to be an announcement from the Japanese-era Taiwan Railway Bureau (台灣鐵道部), listing a number railway stations around the island that were changing their names. Most of the information that was listed on the chart wasn’t particularly new to me, but it was the first time that I had seen it put together, especially on something that looked official.

Honestly, this is an aspect of Taiwan’s history that I’ve probably touched upon more than a few dozen times on my various articles about the Japanese-era, so I thought it best that I put together this article, and make use of the chart to expand upon what took place. One of the other reasons I’m writing this, though, is because there isn’t much information available in the English language regarding some of these original location names. I thought it would be helpful for anyone interested to learn about aspects of Taiwan’s history that aren’t often mentioned.

This time, in lieu of my own photos, I’m just going to share maps of Taiwan from the Japanese-era, which are often beautifully designed, but also feature some of those location names prior to being changed.

Link: Taiwan’s Remaining Japanese-era Train Stations (台鐵現存日治時期車站)

In the early years of the Japanese-era, Taiwan's administrative districts were a bit of a mess, with about twenty somewhat unorganized prefectures (廳). By the time Emperor Taisho (大正天皇) had come to power, the situation in Taiwan had started to become much more organized, and after more than two decades of development, many of the villages, towns and cities that we know today had stated to take shape, with infrastructure in place to properly administer the island.

In 1920 (大正9年), the Japanese government in Tokyo instituted an administrative policy that standardized Taiwan’s geographic administrative areas with those in the rest of the country. Known as the ‘Dōka Policy’ (同化 / どーか), Taiwan’s administrative areas were converted from the original ‘prefectures’ (廳 / cho / ちょう) into the same ‘prefectures’ (州 / shu / しゅう) that were used in Japan at the time. It was during this time that they also reduced the original number of prefectures from twenty to eight.

As of 1920, Taiwan’s eight prefectures were:

Taihoku (臺北州 / たいほくしゅう): Modern day Taipei, New Taipei City, Keelung, Yilan

Shinchiku (新竹州 / しんちくしゅう): Modern day: Taoyuan, Hsinchu, Miaoli

Taichu (臺中州 / たいちゅうしゅう): Modern day: Taichung, Changhua, Nantou,

Tainan (臺南州 / たいなんしゅう): Modern day: Chiayi, Yunlin, Tainan,

Takao (高雄州 / たかおしゅう): Modern day: Kaohsiung, Pingtung

Karenko (花蓮港廳 / かれんこうちょう): Modern day: Hualien

Taito (臺東廳 / たいとうちょう): Modern day: Taitung, Green Island, Orchid Island

Hoko (澎湖廳 /ほうこちょう): Modern day: Penghu Islands

Within each of these prefectures, you would have found subdivisions in the form of cities (市 / し) and counties (郡 / ぐん), which were then divided up into neighborhoods (町 / まち), towns (街 / がい), villages (庄 / そう) and Indigenous communities (蕃地 / ばんち), respectively.

While the colonial government was drawing up all of these new administrative districts, another issue that had to be dealt with were the names of some of these places. While it’s true that many of the major towns and villages around the island kept their original names, the Japanese weren’t exactly the biggest fans of some of them, so they decided to make some changes.

Prior to the arrival of the Japanese in 1895, Taiwan had been inhabited first it’s various tribes of indigenous peoples, then settlers from China started making their way across the strait, followed by the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, English, etc. With names derived from so many different influences, the Japanese sought to create a system that was not only modern, but easier to understand.

For those of you who are interested in the changes, I’ve put together a list of some of the name changes that took place in 1922. It’s a long list, and I’m only going to provide their original name, the name they changed to, and their current name. I won’t spend time translating each of them to Japanese as many of them also appear below:

-

1. Chúi-tng-kha (水返腳) → Sek-chí / Xizhi (汐止) Hokkien origin

2. Sek-kháu (錫口) → Siông-san / Songshan (松山) Hokkien origin

3. Pressinowan (叭哩沙) → Sam-sing / Sanxing (三星) Ketagalan origin

4. Pang-kiô (枋橋) → Pang-kiô / Banqiao (板橋) Hokkien origin

5. Sann-kak-íng (三角湧) → Sam-kiap / Sanxia (三峽) Hokkien origin

6. Kiâm-chhài-àng (鹹菜硼) → Guanˋ si / Guanxi (關西) Hakka origin

7. On Phìn-tsṳ́n (安平鎮) → Phìn-tsun / Pingzhen (平鎮) Hakka origin

8. Rhong moi lag (楊梅壢) → Rhong moi / Yangmei (楊梅) Hakka origin

9. Takoham (大嵙崁) → Thai-hâi / Daxi (大溪) Ketagalan origin

10. Su-gi-na (樹杞林) → Tek-tang / Zhudong (竹東) Hakka origin

11. Co-sân (草山) → Pó-sân / Baoshan (寶山) Hakka origin

12. Tonsuyan (屯消) → Thunsiau / Tongxiao (通霄) Taokas Origin

13. Ataabu (阿罩霧) → Bu-hong / Wufeng (霧峰) Hoanya origin

14. Sann-tsa̍p-tiunn-lê (三十張犁) → Pak-tun / Beitun (北屯) Hokkien origin

15. Thài-pîng (太平) → Tua-pîng / Daping (大平) Hokkien origin

16. Holotun (葫蘆墩) → Hong-guân / Fengyuan (豐原) Saisiyat origin

17. Gû-mâ-thâu (牛罵頭) → Tshing-tsuí / Qingshui (清水) Hokkien origin

18. Ka-tâu (茄投) → Liông-tsínn / Longjing (龍井) Hokkien origin

19. Khóo Ka-ióng (茄苳腳) → Hue-tuânn / Huatan (花壇) Hokkien origin

20. Kuan-tè thiann (關帝廳) → Éng-tseng / Yongjing (永靖) Hokkien origin

21. Huan-á-uat (番仔挖) → Sua-suann / Shashan (沙山) Hokkien origin

22. Chháu-ê-tun (草鞋墩) → Chháu-tùn / Caotun (草屯) Hokkien origin

23. Lâm-ngá (湳仔) → Bêng-kan / Mingjian (名間) Hokkien origin

24. Toukouva (塗庫) → Jîn-tik / Rende (仁德) Siraya origin

25. Tavocan (大目降) → Sin-huà / Hsinhua (新化) Siraya origin

26. Tapani (噍吧哖) → Ta-pa-nî / Yujing (玉井) Taivoan origin

27. Tackalan (直加弄) → An-ting / Anding (安定) Siraya origin

28. Saulang (蕭壠) → Ka-lí / Jiali (佳里) Siraya origin

29. Tiàm-á-kháu (店仔口) → Peh-hô / Baihe (白河) Hokkien origin

30. Tá-bâ (打貓) → Bîn-hiông / Minxiong (民雄) Hoanya origin

31. Muî-a-khenn (梅仔坑) → Sió-muî / Xiaomei (小梅) Hokkien origin

32. Dalivoe (他里霧) → Táu-lâm-tìn / Dounan (斗南) Hoanya origin

33. Phok-a-kioh (樸仔腳) → Phoh-tsú / Puzi (朴子) Hokkien origin

34. Takao (打狗) → Ko-hiông / Kaohsiung (高雄) Makatao origin

35. Han-chî-liâu (蕃薯藔) → Kî-san / Qishan (旗山) Hakka origin

36. Mì-nùng (彌濃) → Mì-nùng / Meinong (美濃) Hakka origin

37. Akaw (阿緱) → Pîn-tong / Pingtung (屏東) Paiwan origin

38. Vangecul (蚊蟀) → Buán-tsiu / Manzhou (滿州) Paiwan origin

39. Má-keng (媽宮) → Má-keng / Magong (馬公) Hokkien origin

In some cases the names of these towns changed completely, but for the most part most of them remained the same, albeit with simple changes in the ‘Kanji’ (Chinese characters) that were thought to make them more ‘elegant.’

To better explain what I mean, I’m going to start by offering a few specific, and probably the most obvious, examples of how these names changed:

The most obvious example of these name changes was in the southern port city that we refer today as Kaohsiung. Originally inhabited by the Makatao (馬卡道族) and Siraya (西拉雅族) indigenous groups, the area was referred as ‘Takau Island’ translating to 'bamboo forest island’ in the indigenous languages. When Chinese settlers arrived in the area, they heard the name ‘Takau’ and assigned the Chinese characters ‘打狗’, which translates literally as ‘beating a dog,’ something none of us should ever do.

When the Japanese arrived in Taiwan, the name of the city remained the same, but in 1920, they changed the Kanji from ‘打狗’ to ‘高雄’ (高雄 / たかお), which had the same 'pronunciation in Japanese. Considered far too crude to be the name of a Japanese city and an international port, the colonial government came up with something that was so good that when the Chinese Nationalists arrived in 1945, instead of changing the name from the Japanese 'Takao', they just left the Chinese characters the same, which is why the city has since been known as ‘Kaohsiung' in the Chinese language.

In a similar case, the town we know today as Minxiong (民雄) also had a name that the Japanese frowned upon - The (then) small village in Chiayi (嘉義) was originally named ’Dovaha’ (擔貍社) by the Dutch, who gave it the name in honor of the Pingpu Tribe (平埔族) that settled there. Later, the name was translated from Dutch into Taiwanese Hokkien as ‘Tá-bâ’ (打貓), or ‘beating a cat.’ Once again, instead of changing the pronunciation of the name, different characters were chosen to represent the town. Pronounced ‘Tamio’ (たみお) in Japanese, the words “民雄” (Hero of the People) were chosen instead.

There are of course other examples of how these name changes took place that didn’t have to do with animal cruelty, or the names being inappropriate. Take Kaohsiung’s district of Gangshan (岡山區) as an example. Originally named ‘A-kong-tiàm‘ (阿公店), or ‘Grandfather’s Shop’, the origin of the name of the town has a few different interpretations. One explanation was that due to its geographic location as a trading space between the ports in Tainan and Kaohsiung, the area was full of stores run by seniors. Hilariously, there are also claims that the name was actually just given to the space because there was an old guy in the middle of no where with a store.

Either way, the name ‘A-kong-tiàm’ didn’t really translate very well to Japanese, so they changed it entirely - The new name for the district of Takao Prefecture, which was being developed as a suburb became known as ‘Okayama’ (岡山 / おかやま), named after one of the Japanese main island’s prefectures. Once again, when the Republic of China took over in the 1940s, the name remained the same, with the pronunciation changed to ‘Gangshan’ instead of ‘Okayama’ and remains so to this day.

There is, however, a reservoir in the area that retains the ‘A-kong-tiàm’ name, a nod to the town’s history.

My final example before moving on is one that is simply just a linguistic difference between Chinese, Taiwanese and Japanese, and most of the name changes that took place are due to these linguistic differences. If I use the Japanese-era ‘Shanjia Train Station’ (山佳車站) as an example, the original name of the area was ‘Suann á kioh’ (山仔腳), referring to its location at the foot of a mountain. The problem was that the character ‘仔’(zai), which is quite common in Taiwanese Hokkien isn’t very common in Japanese.

When it came to characters that weren’t commonly used in Kanji, like this, they simply replaced the ‘仔’ with a similar, simplified version of the character, like ‘子’, for example.

With these examples, I think you should have somewhat of an introduction to the thought process behind some of these changes. In some instances, the Japanese felt the names were inappropriate, in others they just didn’t translate well, and in others, they were simplified for convenience. Below, I’ll list each of the name changes that are displayed on the chart.

At this time, I’m not going to go into detail about the origin of each of the names, but I will provide their original name, their Japanese-era name, and their current name so that you can better understand how these things have evolved over time. If you’re interested in the linguistic changes mentioned in the third example above, click the drop down below, where I’ve provided a list of the most common character changes:

-

‘(á) zi’ 「仔」was changed to ‘zi’「子」

‘hong’「藔」was changed to ‘liáo’「寮」

‘hun’ 「份」was changed to ‘fèn’ 「分」

‘bei’ 「陂」was changed to ‘po’ 「坡」

‘shén’「什」was changed to ‘shí’「十」

‘tun’「墩」was changed to ‘tún’「屯」

‘ào’「澚」was changed to ‘ào’「澳」

‘gang’「崗」was changed to ‘gang’「岡」

‘khu’「坵」was changed to ‘qiu’「丘」

‘muâ’「蔴」was changed to ‘má’「麻」

‘diàn’「佃」was changed to ‘tián’「田」

Now, let me spend some time dissecting the inspiration for this article, the photo that appeared on my social media feed, all of which I’ve broken up and translated for you below:

To start, in the direct center of the diagram, you’ll find the vertical text: “Taisho Year 11, Taiwan Railway Station Name Change Chart” (大正十一年台灣鐵道停車場中改稱名新舊對照表), splitting the diagram into four different sections, or regions of the island.

For each of the stations, I’ll start with their original Japanese name, their name after being changed, and then their current name. I’ll also provide a link to each of the stations for any of you who are interested in learning more about the stations, many of which are now well-over a century old.

Note: In some cases, the romanization of these names could be a bit off, but I’ve done my best translating from several different languages to give readers a better idea of these changes.

Starting in the south, we have the following eleven name changes:

Chushusou Station (中州庄乗降場) → Chushu Station (中州驛 / ちゅうしゅうえき) → Zhongzhou Station (中洲車站)

Shinshigai Station (新市街驛 / しんしがいえき) → Shinshi Station (新市驛 / しんしえき) → Xinshi Station (新市車站)

Wanri Station (灣裡驛/わんりえき) → Zenka Station (善化 / ぜんかえき) → Shanhua Station (善化車站)

Hanshiten Station (番仔田停車場) → Hanshiten Station (番子田驛 / はんしてんえき) → Longtian Station (隆田車站)

Shin’eisho Station (新營庄驛 / しんえいしょうえき) → Shin’ei Station (新營驛 / しんえいしょうえき) → Xinying Station (新營車站)

Koheki’ryo Station (後壁藔停車場 / こうへき りょうえき) → Koheki Station (後壁驛 / こうへきえき) → Houbi Station (後壁車站)

Suikuttao Station (水堀頭驛 / すいほりとうえき) → Suijo Station (水上驛 / すいじょうえき) → Shuishang Station (水上車站)

Dabyo Station (打猫驛/だびょうえき) → Tamio Station (民雄驛 / たみおえき) → Minxiong Station (民雄車站)

Taihorin Station (大莆林驛 / たいほりんえき) → Tairin Station (大林驛 / たいりんえき) → Dalin Station (大林車站)

Tarimu Station (他里霧驛 / たりむりんえき) → Toroku Station (斗六驛/とろくえき) → Douliu Station (斗六車站)

Nihachisui Station (二八水驛 / にはちすいえき) → Nisui Station (二水驛) → Ershui Station (二水車站 / にすいえき)

On the top right, we have the following eleven name changes in the north:

Komota Station (紅毛田驛 / こうもうたえき) → Komo Station (紅毛驛 / こうもうえき) → (1934) Chikuhoku Station (竹北驛/ちくほくえき) - Chubei Station (竹北車站)

Taikoko Station (大湖口驛 / たいここうえき) → Kokō Station (湖口驛 / ここうえき) → Hukou Station (湖口車站)

Yōbair Station (楊梅壢驛 / ようばいれき) → Yobai Station (楊梅驛 / ようばいえき) → Yangmei Station (楊梅車站)

Heianchin Station (平安鎮驛 / へいあんちんえき) → Heichin Station (平鎮驛 / へいちんえき) → Puxin Station (埔心車站)

Kanshikyaku Station (崁仔脚驛 / かんしきゃくえき) → Kanshikyaku Station (崁子脚驛 / かんしきゃくえき) → Neili Station (內壢車站)

Okaishi Station (鶯歌石驛 / おうかいしえき) → Oka Station (鶯歌驛 / おうかえき) → Yingge Station (鶯歌車站)

Yamakogashi Station (山仔脚驛 / やまご あしえき) → Yamakogashi Station (山子腳驛 / やまご あしえき) → Shanjia Station (山佳車站)

Bankyo Station (枋橋驛 / ばんきょうえき) → Itahashi Station (板橋驛 / いたはしえき) → Banqiao Station (板橋車站)

Báng-kah Station (艋舺驛 / まんかえき) → Manka Station (萬華驛 / まんかえき) → Wanhua Station (萬華車站)

Suzuko Station (錫口驛 / すずこうえき) → Matsuyama Station (松山驛 / まつやまえき) → Songshan Station (松山車站)

Suihenkyaku Station (水返脚驛 / すいへんきゃくえき) → Shiodome Station (汐止驛 / しおどめえき) → Xizhi Station (汐止車站)

On the bottom left, we have the following eleven name changes on the east coast and in the south of Taiwan.

Suo Station (蘇澚驛 / そおうえき) → Suo Station (蘇澳驛 / そおうえき) → Su’ao Station (蘇澳車站)

Togazan Station (冬瓜山驛 / とうがざんえき) → Tozan Station (冬山驛 / とうざんえき) → Dongshan Station (東山車站)

Nonnongai Station (暖暖街驛 / だんだんがいえき) → Nonnon Station (暖暖驛 / だんだんえき) → Nuannuan Station (暖暖車站)

Tonbutsu Station (頓物驛 /とんぶつえき) → Takeda Station (竹田驛 / たけだえき) → Zhutian Station (竹田車站)

Ako Station (阿緱驛 / あこうえき) → Heito Station (屏東驛 / へいとうえき) → Pingtung Station (屏東車站)

Takao Station (打狗驛 / たかおえき) → Takao Station (高雄驛 / たかおえき) → Kaohsiung Station (高雄車站)

Nanshiko Station (楠仔坑驛 / なんしこうえき) → Nanshi Station (楠摔驛 / なんしえき) → Nanzi Station (楠梓車站)

Kyokoto Station (橋仔頭驛 / きょうことうえき) → Kyokoto Station (橋子頭驛 / きょうことうえき) → Qiaotou Station (橋頭車站)

Akotentei Station (阿公店驛 / あこうてんていえき) → Okayama Station (岡山驛 / をかやまえき) → Gangshan Station (岡山車站)

Hanrochiku station (半路竹驛 / はんろちくえき) → Rochiku Station (路竹驛 / ろちくえき) → Luzhu Station (路竹車站)

Daikogai Station (大湖街驛 / だいこがいえき) → Daiko Station (大湖驛 / だいこえき) → Dahu Station (大湖車站)

Finally, on the bottom right, we have the following eleven name changes in central Taiwan:

Tanakaou Station (田中央驛 / でんちゅうおうえき) → Tanaka Station (田中驛 / でんちゅうえき) → Tianzhong Station (田中車站)

Katokyaku Station (茄蔘腳驛 / かとうきゃえき) → Kadan Station (花壇驛 / かだんえき) → Huatan Station (花壇車站)

Daito Station (大肚驛 / だいとえき) → Oda Station (王田驛 / おうたえき) → Chenggong Station (成功車站)

Tanshiken Station (潭仔乾驛 / たんしけん) → Tanshi Station (潭子驛 / たんしえき) → Tanzi Station (潭子車站)

Koroton Station (葫產激驛 / ころとんえき) → Toyohara Station (豐原驛 / とよはらえき) → Fengyuan Station (豐原車站)

Korisou Station (后里庄驛 / こうりそうえき) → Kori Station (后里驛 / こうりえき) → Houli Station (后里車站)

Taiankei Station (大安溪驛 /だいあんけいえき) → Tai’an Station (大安驛 / たいあんえき) → Tai’an Station (泰安車站)

Sansagawa Station (三叉河驛 / さんさがわえき) → Sansa Station (三叉驛 / さんさえき) → Sanyi Station (三義車站)

Dorawan Station (銅鑼灣驛 / どうらわんえき) → Dora Station (銅鑼驛 / どうらえき) → Tongluo Station (銅鑼車站)

Koryu Station (後壠 /こうりゅうえき) → Koryu Station (後龍驛 / こうりゅうえき) → Houlong Station (後龍車站)

Chuko Station (中港驛 /ちゅうこうえき) → Chikunan Station (竹南驛 / ちくなんえき) → Zhunan Station (竹南車站)

Now that we’ve got all of that out of the way, it’s time to talk a little about the photo, and some rather obvious aspects of it that I probably should have noticed much earlier than I did.

The old adage ‘a picture tells a thousand words’ proves quite important with regard to the chart. You could argue that it’s not exactly a ‘picture,’ nor are there a thousand words on it, but after studying it for a while, I started to notice things that wouldn’t have been there if it were an original announcement from 1922. One of the first things that I should have noticed was that on the very top of the chart, under the two crests, the words “Showa Era” (昭和時代) and “Taisho Era” (大正時代).

The problem with this was that if the chart was released in 1922, it would be a bit strange to see the acknowledgement of the Showa Era there, given that it started on December 25, 1926, and lasted until the death of Emperor Showa on January 7th, 1989. Those ‘era’s are repeated once again at the top of the chart in smaller-case font with the addition of the Meiji Era (明治時代), which preceded the Taisho era. Essentially, the chart was more or less just listing the three emperors who oversaw control of Taiwan during the Japanese-era.

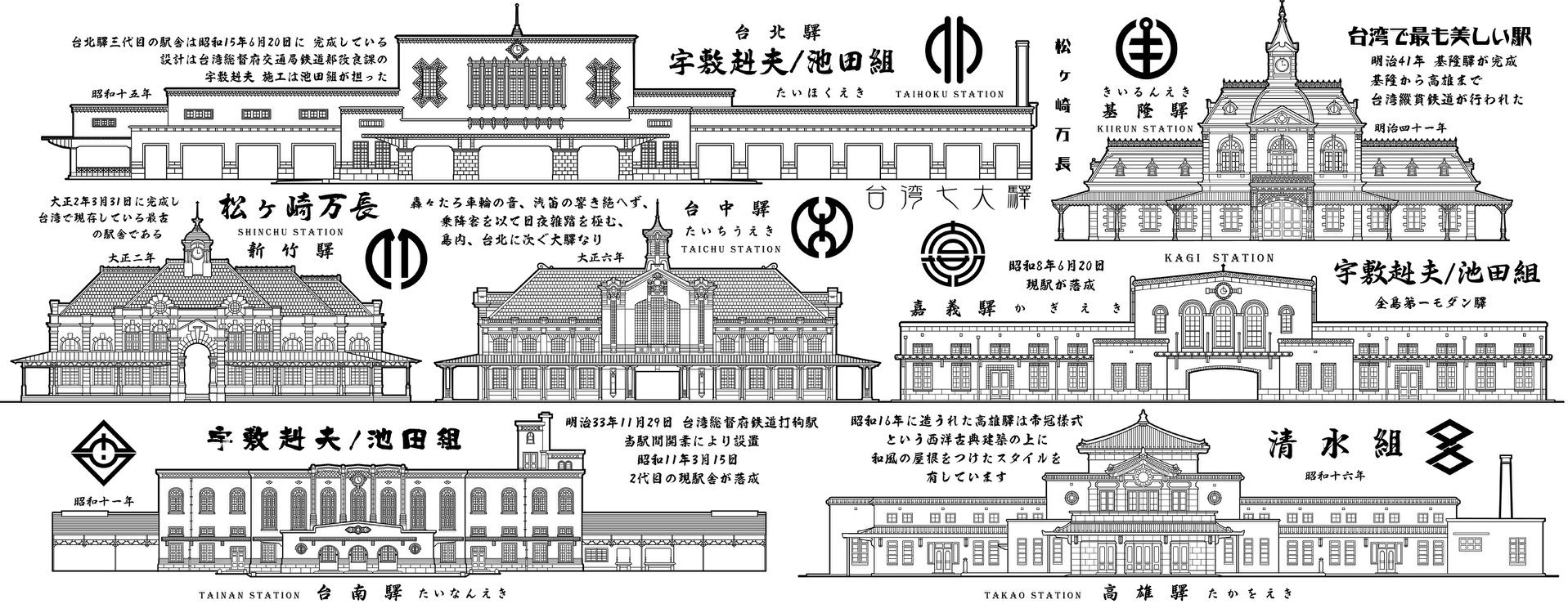

What I should have noticed from the outset were the words “Taiwan Restoration” (台湾維新) - You’ll have to forgive me if what I say here seems like an advertisement, but a few years back I purchased a beautifully designed poster-like print that featured the logos that represented Taiwan’s various cities during the Japanese-era. Design-wise, I’m a big fan of them, especially compared to the ghastly logos that are used these days.

I purchased the print at a local bookstore, but it was produced by the very same ‘Taiwan Restoration’ person (or group) mentioned above. While you can still find quite a few of their designs for sale online, they haven’t really been very active updating their social media page in the past few years, so I can’t really tell you if it’s all being designed by a single person or a group of people. What I can tell you is that they’re (probably) not affiliated with the ‘Taiwan Renewal Party’, which shares the same Chinese name.

Link: Taiwan Restoration (Facebook) | Ruten Store: 台湾維新 | GJ Taiwan Store

Taking a look at the Facebook page, it strikes me that the products that they’re selling are all designed quite well, making use of some of the iconography that was prevalent during the Japanese-era. Obviously, as I mentioned earlier, I’m a fan of the logos that were created to signify Taiwan, and its major towns and cities. That being said, they’ve designed quite a few things that celebrate Taiwan’s railroad, which I really appreciate.

Now that I’ve done some looking into their products, I might actually try to purchase some more, if they’re still available. Unfortunately, it seems like quite a few of their products are sold out, have been for some time, and I’m not particularly sure if they’ll ever be restocked.

Nevertheless, before I leave you, with regard to all of the name changes that took place in Taiwan during the Japanese-era, the diagram above only features a small percentage of the location names that were changed. This is because it is only a representation of the railway stations that changed their names to reflect the changes in their community. The evolution of how these names of places around the country have changed over the centuries is a subject that is not covered very well in the English language, but it is a fascinating topic that paints a much broader story of how this beautiful island has changed as it has developed over the past few centuries.

References

臺灣鐵道旅行案內 (國家文化記憶庫)

Taiwan Restoration Facebook (台湾維新)

臺灣日治時期行政區劃 (Wiki)