Walking around Taipei’s Ximending Shopping, have you ever come across the random bell tower on the side of the road? If so, you might have asked yourself: “What’s the deal with that Japanese-looking thing in one of the city’s hippest urban areas?” Today, I’m here to answer that question, and possibly any others you might have about this piece of the city’s history.

Suffice to say, ‘Ximending’ (西門町), might never have become the popular place it is today without these buildings, and the urban development that came with them. So, in this article, I’m going to focus on the modern history of Ximen, introduce the building which was once located next to the bell tower, and the park that exists there today.

As usual, I’m going to provide some pretty in-depth information about some of these things, so if you just want to know about what exists there today, feel free to scroll down below to where I introduce the ‘Nishi Honganji Relics’ section, which focuses on the contemporary usage of the land as a public park and cultural space, a short distance away from the hustle and bustle from what has become known as the ‘Mecca’ of Taiwan’s youth culture.

Ximending (西門町 / せいもんちょう)

It’s unlikely that there are many people who visit Ximen today who stop and think: “I wonder what this place looked like a century ago?” The modern shopping district that we know and love has developed so much over the past few decades that it doesn’t even resemble a shadow of its former self. But this is what I do, I stop and look at things and try to appreciate the long history that helped to transform parts of our communities into what they are today.

Well over a century prior to becoming known as the “Shibuya of Taipei” and the arrival of all of its theaters, night clubs, karaoke bars and shopping, the ‘Ximen’ area was simply just a patch of swampy wilderness outside of the city’s ‘Baocheng Gate’ (寶成門), the Qing-era gate, more commonly known as the ’West Gate’ or ‘Ximen’ (西門), in Mandarin, which is where the area derives its name.

When the Japanese arrived in Taiwan in 1895 (明治28年), the area was completely undeveloped and consisted primarily of dengue-infested swamps, part of the first generation railway, and a road between the walled area of the city (台北城內) and Bangkha (艋舺), or Wanhua (萬華). Showing little interest in the confined nature of Chinese-style walled cities, the Japanese quickly got to work knocking them down in order to carry out their grander plans for massive urban development in what would be the capital of the empire’s new overseas colony.

Note: For a bit of scale, if you walked from the North Gate (北門) to the Ximen MRT Station (where the original west gate once stood), it would likely only take you about ten minutes. That walk would essentially consist of half of the walled area that was the ‘Taipei’ of the Qing-era. That being said, there were other developed areas nearby like Dadaocheng (大稻埕) and Bangkha (艋舺) that were located outside of the walls. Nevertheless, old Taipei was just a very small piece of one of the neighborhoods within the capital today.

Much of the development of the city in the initial years of the Japanese Colonial Era was influenced by the re-construction (re-routing) of the railway, which was essential to the empire’s plans for exerting control over the island as well as extracting its precious natural resources. With the railway from the northern port city of Keelung running through the north-eastern portion of Taipei, it curved in a south-western direction and made its way through Ximen and Bangkha before crossing the river on its way further south.

Having the Qing-era walls in the area complicated the construction of the south-bound railway out of the city, which was re-routed from the original track laid by the Qing a decade or so earlier. Within the first decade of the colonial era, the city developed at an almost inhuman speed with roads, public works and new buildings popping up all over the place. With all of the construction taking place, it might have seemed like the early years were all-work-and-no-play, so the government made the decision to follow the example of East Tokyo’s popular Asakusa District (浅草 / あさくさ), a specialized entertainment and economic area, and came up with plans to develop the land near the old Western Gate.

Taking inspiration from the Qing-era gate, the Japanese named the neighborhood “Seimon-chō” (西門町 / せいもんちょう), which translates directly to ‘Ximending’ in Mandarin. Starting in 1897 (明治30年), the area became home to business and entertainment facilities starting with the Taihokuza Theater (臺北座 / たいほくざ), then the Eiza Theater (榮座 / えいざ) and the still existing Seimon-cho Market and Department Store (西門市場八角樓), known today as the Red House Theater (紅樓劇場). In addition to theaters, markets and department stores, Ximen also became home to a number of restaurants and bars, marking the start of an entertainment, shopping and fine dining paradise, something which hasn’t changed for more than a century.

Link: Kishu An (紀州庵文學森林)

Business and entertainment in the area continued to thrive throughout the Japanese-era as the number of theaters continued to expand. When the Second World War ended and the Japanese were forced to surrender control of Taiwan, they left the citizens of the capital with a well-established appreciation for motion pictures and entertainment, and that is something that carried on in the post-war period as ‘Ximen’ continued its expansion, consuming the Japanese-era neighborhoods known as Wakatake-chō (若竹町 / わかたけちょう), Shinki-chō (新起町 / しんきちょう), Suehiro-chō (末廣町 / すえひろちょう), Kotobuki-chō (壽町 / ことぶきちょう) and Tsukiji-chō (築地町 / つきじちょう).

Today, the shopping district is home to over twenty theaters and thousands of stores and vendors catering to an estimated three million visitors per month. The modern era however hasn’t been all fun and games for Ximen though - In the early 1990s, business in the district declined as there was a shift towards the East District (東區) of the city, where massive department stores were constructed. Lending a hand to the struggling Ximen, the Taipei City Government designated the district as the Ximending Pedestrian Area (西門町商圈行人徒步區), prohibiting vehicles from entering the area on weekends and national holidays. Then, in 1999 (民國88年), the Ximen MRT Station (西門捷運站) opened for service and assisted in bringing the district back to life, offering quick and convenient access.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has proved to be yet another nail to the heart of the shopping district with many vendors forced to shut their doors due to the lack of tourists, shopping and high cost of rent.

Once we put this pandemic behind us, you can be sure that this historic entertainment district will once again make its triumphant return, and all the ‘for rent’ signs we see now will quickly disappear!

Changing so much over the past century, it is surprising, yet heartening that we can still find some historic locations among the constantly changing face of the district’s urban landscape. Given that Ximen was developed during the Japanese-era (1895-1945), it should go without saying that the vast majority of the historic attractions you’ll come across in the area are related to that period of Taiwan’s history.

Some of those historic locations we can enjoy are the Red House Theater (which was recently restored), the Taipei Mazu Temple (台北天后宮), originally a Japanese Buddhist temple (Hong-Fa Temple 弘法寺 / こうぼうでら), Fahua Temple (Hokke-ji / 法華寺 / ほっけじ) and the subject of this article, the Nishi Hongan-ji Park.

Nishi Hongan-ji Temple (西本願寺)

Taking inspiration from Tokyo’s Asakusa District, the Ximending Shopping and Entertainment District was also home to some important places of worship. Just like the ancient Sensō-ji Buddhist Temple (金龍山浅草寺 / せんそうじ) back in Tokyo, Ximen was chosen as the home for the Taiwan Branch of the Nishi Hongan-ji Buddhist Temple (西本願寺台湾別院 / ほんがんじたいわんべついん).

While it certainly wasn’t comparable in size to the ostentatious ‘Buddhist’ temples you’ll find in Taiwan these days, the Nishi Hongan-ji temple was one of Taiwan’s first massive places of worship, when it was completed, it dominated the city’s skyline.

Constructed as the ‘Taiwan Branch’ of Kyoto’s Nishi Hongan-ji temple (西本願寺), the temple was part of the “Pure Land” sect of Buddhist temples, better known as the Jōdo Shinshū (浄土真宗). As one of Japan’s largest Buddhist organizations, the massive Taiwan branch was constructed in an attempt to show the power and prestige of the group and its eagerness to expand its number of followers in the colony.

Links: Nishi Hongan-ji | Jōdo Shinshū (Wiki)

Regarded as a Japanese National Treasure and designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Nishi Hongan-ji Temple in dates back to 1591, and is one of the most widely visited destinations in the historic Japanese capital of Kyoto. Officially known as the “Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-ha” (淨土真宗本願寺派 / じょうどしんしゅうほんがんじは) sect, there are more than a hundred branches throughout Japan, and the organization has expanded internationally over the years with branches constructed around the world.

As one of the organization’s first overseas branches, the Jodo Shinshu were one of the first Japanese Buddhist organizations to land in Taiwan. Monks were embedded within the ranks of the army and were tasked with comforting soldiers on expedition, taking care of the injured, holding Buddhist funerals for the deceased and escorting their remains back to Japan.

The history of the ‘Taiwan Branch’ got its start in 1897 (明治30年) when the group purchased around 8300㎡ (2500坪) of land in Taipei’s Shinki-chō (新起町 / しんきちょう). A few years later, thanks to a generous grant of 25,000 Yen from the headquarters back in Kyoto, the colonial government approved an application to construct a ‘temporary’ temple complex located near where the park is located today. With plans for a future migration to a permanent home, the temporary location was set up with a Main Hall (本堂), Assembly Hall (集會所) and dormitories for the monks.

The ‘temporary’ situation lasted until the early 1920s, when the colonial government implemented an ambitious urban development plan (市區改正) that re-shaped and modernized the city by improving roads and constructing public works that took care of sanitation and sewage. Given that parts of the temple were located in an area that was slated for the construction of a major road (currently Changsha Street 長沙街), the group purchased an additional plot of land just south of where the new road would be constructed.

Portions of the original temple had to be demolished and reconstructed to comply with the urban development plan, however it was a relatively fortunate situation, as the plot of land originally occupied by the temple connected directly to the new plot.

This meant that they had more space and were were able to move things around, and eventually expand.

In 1922 (大正11年), the Mausoleum (御廟所 /ごびょうしょ), Bell Tower (鐘樓 / しょうろう) and Jushin Assembly Hall (樹心會館 / じゅしんかいかん) were completed. Then, in 1924 (大正13年), the abbot’s official residence (輪番所) was reconstructed. It would take until 1931 (昭和6年) however for the massive Main Hall (本堂 / ほんどう) to officially re-open its doors.

At nearly 1000㎡ (300坪), the Main Hall was constructed on a large reinforced concrete base facing east in the direction of the Governor General’s Office. The upper section of the building, including much of its giant roof was constructed of Taiwanese Red Cypress (紅檜). The interior space of the building featured high-ceiling space and its size was measured in an old style of measurement listed as seven ‘bays’ wide and seven ‘bays’ in length (正面七開間,縱深亦為七開間), which is approximately 31.5 meters in length and width in metric and reached a height of around 76 feet, equal to a seven or eight story building by today’s standards.

In addition to the upper floor space, the concrete base was also functional in that it included space for a library, conference rooms, etc. The interior space on the upper floor was divided into two different sections, the outer section (外陣) and the inner sanctum (內陣) with the outer section occupying the majority of the space featuring large sliding panel doors on the three sides of the front half of the building and a large open space for meditation and worship. The inner sanctum on the other hand would have been home to an area that was cordoned off, accessible only to the monks at the temple with a large shrine against the rear wall.

The architectural design of the Main Hall largely followed that of the Goeidō Hall (御影堂), known in English as the “Founders Hall”, at Kyoto’s Nishi Hongan-ji Temple. Historic photos of the interior of the Taipei temple match up quite well with what we can see today at the historic building in Japan, but more notably, the roof of the building in Taipei was designed to be almost a replica of the original.

One of the saddest things about the loss of this building is that there are few traditional buildings from the Japanese-era that remain in Taiwan which feature a roof as grand as what you would have seen at this temple. The few that come close would be the Tainan Martial Arts Hall, Changhua Martial Arts Hall, or the Taoyuan Shinto Shrine, however none of them were comparable in size, and each of them vary in their architectural design.

Note: It’s important to remember that even though the height of the building was a total of 76 feet, at least three quarters of its total size would have been the roof, which was meant to display the grand nature of the building. The importance of the roof’s architectural design cannot be understated, and it is what made the building so iconic.

Where the building’s roof was similar to many of the other traditional Japanese-style buildings around Taiwan was that it was designed in the ubiquitous irimoya-zukuri (入母造 / いりもやづくり) architectural style. More commonly known as the ‘East Asian hip-and-gable roof’ (歇山), these roofs essentially consist of a ‘hip’ section that slopes down on all four slides and a ‘gable’ section on the opposing sides. Originally taking inspiration from Chinese-style architectural design, the Japanese irimoya style evolved over the centuries and began to take shape as mastery over construction techniques improved.

Links: East Asian hip-and-gable roof (Wiki) | Irimoya-zukuri 入母屋造 (JAANUS)

The roof at the Taipei temple followed the same irimoya-style hip-and-gable roof as what you’d find at Nishi Hongan-ji back in Kyoto, but as it was a much newer structure, the construction techniques differed slightly. The Taipei temple made use of iron trusses within the interior of the building in addition to the reinforced concrete pillars on the exterior that extended from the base to the roof to help to stabilize it’s massive weight.

Where it remained the same however, and what would make it rare in Taiwan today, was that it featured a very steep slope on the ‘hip’ with ‘hongawarabuki’ (本瓦葺 / ほんかわらぶき) tiles. These tiles, which are a mixture of flat broad concave tiles (平瓦 / hiragawara / ひらがわら) and semi-cylindrical convex tiles (丸瓦 / marugawara / まるがわら) created a visual effect that made the roof look as if it were an incoming tsunami.

I’m sure all these official names don’t make a lot of sense to most people, so to explain it simply, the cylindrical tiles are laid first and looked like giant bamboo trees running down the length of the roof. The flat tiles on the other hand ran horizontally and acted as protective covers for the seams or joints where they met.

At the top of the roof there was a thick ‘oomune’ ridge that ran horizontally along the length of the building decorated with ‘shishiguchi’, or ‘lion-mouth tiles’ on the ends. Running vertically down the roof were similarly decorated ridges known as ‘kudarimune’ and next to them ‘corner’ ridges that are split into two sections referred to as ‘sumimune’ and ‘chigomune’ on the end. Finally, on the ends of each of the triangular gable sections you’d find beautifully decorated gegyo (懸魚 / げぎょ) ‘hanging fish’ wooden boards, used as a charm against fire, similar to porcelain dragons on Taiwanese temples.

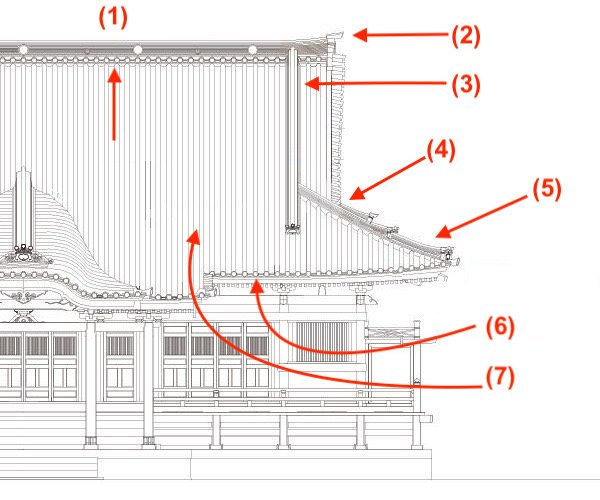

Once again, you’re being inundated with a bunch of technical terms, so I’ll provide a diagram blow that points to each of the functional and decorative aspects of the roof just mentioned:

oomune (大棟 / おおむね) - the ridge that runs along the top of the roof.

shishiguchi (獅子口 / ししくち) - decorative ‘lions-mouth’ elements on the edges of the ridge.

kudarimune (降棟 / くだるむね) - a ridge that descends vertically from the top ridge.

sumimune (隅棟 / すみむね) - a corner ridge that connects to the gable.

chigomune (稚児棟 / ちごむね) - the end of the corner ridge, decorated with shishiguchi (2).

marugawara (丸瓦 / まるがわら) - semi-cylindrical convex roof tiles that look like bamboo.

hiragawara (平瓦 / ひらがわら) - flat roof tiles that lie between the marugawara (6).

Sadly, after the war, the temple complex was used for a variety of purposes, which prior to the ‘February 28th Incident’ was occupied by the infamous Garrison Command, which rounded up political prisoners and took them to the temple for interrogation, imprisonment, or worse. Later, it was used as housing for a merry-go-round of refugees who came to Taiwan with the Chinese Nationalists. The number of people coming and going from the temple became a precarious issue and ultimately, the grounds became home to illegal squatters, which left it in pretty terrible shape, before it caught fire and burnt to the ground in 1975 (民國64).

After much of what once existed was destroyed, the grounds became home to even more illegal squatters, who set up their own little village of tin-sheeted houses (鐵皮屋), something that was highly frowned upon by the government, especially in one of the city’s most important districts.

And that ladies and gentlemen is where I’m going to move on to the current situation regarding the Nishi Hongan-ji Relics Park!

Nishi Hongan-ji Relics Park (西本願寺廣場)

The historic and cultural value of the grounds were largely ignored until the city had enough of the eyesore next to one of its most important shopping and business districts. In 2006 (民國95年), an urban renewal initiative that sought to knock down the illegal squatter village simultaneously recognized what little remained of the temple as a Protected City-Level Monument (市定古蹟). By 2011 (民國100年), the remaining residents on the grounds were relocated, and a project to convert the grounds into an urban green park, with restoration on the few remaining temple structures were set to be the main attraction.

Restoration of the buildings and the space were officially completed in 2014 (民國103年), and a breath of life was brought back to the historic grounds, reborn as ‘Nishi Hongan-ji Square’ (西本願寺廣場), a multi-purpose park and cultural space gifted to the residents of Taipei.

Unfortunately, it goes without saying that much of what once existed on the grounds has become a distant memory as the various fires over the decades left the majority of once existed in ruins. Lost from the original temple are the Main Hall (本堂), the Mausoleum (御廟所), the Administration Building (庫裏), the Sanmon Gate (山門 / さんもん), and the monks dormitories. What was able to be saved however are the beautiful Bell Tower (鐘樓), the Jushin Assembly Hall (樹心會館), the Abbot’s Residence (輪番所), and the concrete base of the Main Hall.

Below, I’ll briefly introduce each of the remaining pieces of the temple individually, and the purpose they serve today as park of the urban culture park.

Bell Tower (鐘樓 / しょうろう)

The Bell Tower, an integral part of a Japanese Buddhist temple was located within the interior of the complex, just past where the Main Gate (山門) once stood. Coincidentally, once of the smallest parts of the original temple, the Bell Tower today serves as the park’s main attraction. Despite not burning down with many of the other sections of the original temple, the original Bell Tower met with a similar fate as the village of squatters more or less just built around the original base of the tower, consuming it into their village.

Completely reconstructed based on the design of the original, the Bell Tower today features a massive Bonshō bell (梵鐘 / ぼんしょう) housed within what is known in Japan as the “shōrō” (しょうろう). Japanese-style Bell Towers typically fall into two different styles of architectural design, both of which can still be enjoyed in Taipei today - The first type is the most traditional variety known as “hakamagoshi” (褲腰), typically a walled two-storey hour-glass shaped building with the bell located on the second floor. This type can be viewed at the nearby at the historic Soto Zen Daihonzai Temple (曹洞宗大本山別院) as well as the Chin'nanzan Gokoku-ji Temple (鎮南護山國禪寺), each of which are only a few stops away on the MRT.

The second type is considered a ‘newer’ (13th century “new”) variety known as “fukihanachi“ (吹放ち), which is essentially an open structure with no walls, and a bell hanging in the middle.

Within both of these architectural styles, the common feature is that they are typically adorned with a beautiful Japanese-style gabled (切妻造) or hip-and-gable (入母屋造) rooftop. In the case of this Bell Tower, the roof is absolutely beautiful and has to be enjoyed close up. The restoration team obviously spared no effort in ensuring that the roof of the bell tower remained faithful to the original and took special care to have Japanese experts assist in the construction process.

The four sided hip-and-gable roof of the tower features a sloping roof with triangular ‘tsuma’ (妻 / つま) on each of the gable-ends. Designed and decorated similarly to the roof of the former Main Hall, the roof consists of many of the decorative elements mentioned above - What you’ll want to pay the most attention to however are the amazing carpentry skills that make up the network of support trusses within the roof. Working together with the four pillars that connect to its cement base, the trusses are both functional as well as beautiful in their decorative designs.

Bell Towers serve both practical and symbolic purposes as they are thought to have the power to 'awaken people from the daze of everyday life and the pursuit of worldly things like fame and fortune’ and the daily ringing of the bells is a reminder to people of all walks of life to slow down and enjoy life. Even though the Bell Tower serves as a reminder of the beautiful temple that once occupied this space, the bell is only rung on special occasions.

Jushin Assembly Hall (樹心會館)

Dating back to 1923 (大正12年), the Jushin Assembly Hall (樹心會館) was an interesting addition to the temple complex. The ’T-shaped’ Japanese-Western fusion building was constructed with a mixture of brick and wood and features a Japanese-style roof and a ‘karamon’ (唐門 / からもん) entrance. The interior of the building however is considered western-style and was meant to show off the ‘modernity of the era’ (表現新時代精神), with it’s open space and western-style roof trusses. The brick building features quite a few large windows, allowing for considerable amount of natural light in the building during the day, which helps the iconic Taiwan Renga (台灣煉瓦株式會社) red bricks to shine.

Originally used as a space to educate visitors in Buddhist doctrine, the building today is operated by the Taipei City Department of Cultural Affairs and is used as an exhibition and event space. Unfortunately, the space isn’t always open to the public, so if you visit, you may not be able to explore the interior of the building.

Abbot’s Residence (輪番所)

The former Abbot’s Residence is a simple Japanese-style wooden residential-style dormitory that was elevated off of the ground on a cement base. Similar to many of the other Japanese-era houses that I’ve written about over the years, the house was beautifully restored by the city government and the exterior features recently planted cherry trees along the walkway to its entrance that bloom in the winter.

While the residence is ‘technically’ open to the public, it is currently occupied by the ‘Eighty-Eightea Rinbansyo’ (八拾捌茶輪番所), a popular tea house that promotes Taiwanese tea. Despite being a popular destination for Instagrammers, the interior of the building has some pretty strict guidelines with regard to photography, and more or less only allows people with smart phones to take photos, unless a permit is applied for beforehand.

The leasing of the building to the tea shop is part of a government effort to make use of these historic buildings for commercial purposes, recouping some of the public funds used for the restoration of the park - something which I’ve written about in the past.

Link: The role of Public-Private Partnerships in Conserving Historic Buildings in Taiwan

In the future, I’ll likely write a dedicated article about the Abbot’s Residence and the Tea House that occupies the space today, but it’s one of those experiences that I’ll have to plan long in advance in order to be able to take proper photos within the historic residence.

Link: Eighty-Eightea (八拾捌茶)

Open Daily from 11:30 - 6:00pm

Base of the Main Hall (本堂臺座)

Taipei 101 might be one of the most iconic structures in the modern capital of Taiwan, but its safe to say that the original Main Hall of this temple (in addition to a few others) were the Japanese-era equivalent. The historic photos of the building that you can see above are an important reminder of the once iconic building that dominated the city’s skyline.

Even though the building was destroyed, the Taipei City Government restored the reinforced concrete base of the building to ensure that its memory can be enjoyed for years to come. The base, which was restored and renovated along with the rest of the park is currently home to the Taipei City Archives (臺北市立文獻館), and features some important historic exhibitions where you learn about the city’s history. The stairs of the base are likewise a pretty popular spot for residents of the city to relax, enjoy their lunch, or chat with friends.

The City Archives are open to the public Monday to Friday from 9:00am - 5:00pm.

Entry is Free of Charge

Getting There

Address: #174-176 Zhonghua Road, Section 1, Wanhua District, Taipei City

GPS: (25.040200, 121.507290)

Located a short distance from Taipei’s popular Ximending (西門町) shopping district, the Nishi Hongan-ji Square is a beautiful natural space that highlights the history of the Ximen area. Given that it is within walking distance of not only the shopping district, but all of the other historic and cultural attractions in the area, a visit to the park is one that won’t take too much time out of your day.

Conveniently located just south of Ximen’s MRT station, getting there is pretty simple.

Due to its proximity to the MRT Station, I’m not going to provide information for anyone driving a car this time.

If you’ve got a car, simply input the address provided above and you’ll be able to map out your route pretty easily. That being said, the Ximen area is one of the busiest and hippest parts of town, so parking your car nearby can be both frustrating and expensive. I highly recommend you just park it elsewhere and make use of the city’s excellent public transportation, instead.

MRT

The easiest and probably the most convenient way to get to the area is to make use of Taipei’s excellent MRT network. The Nishi Hongan-ji Relic Square is located a three or four minute walk from Ximen Station (西門站) on the network’s Blue Bannan Line (板南線). Once you’ve arrived at the station, you’ll want to take Exit 1 (1號出口) and walk south on either Zhonghua Road (中華路) or Hanzhong Road (漢中路), where you’ll also see the iconic Ximen Red Building (西門紅樓).

Bus

In addition to the MRT, Taipei’s Public Bus network is also pretty useful, especially if you’re coming from an area where you’d have to transfer trains a few times. The most convenient bus stop is located next to Ximen Station, which has almost two dozen different bus routes coming from all over the city. With so many buses, it’s difficult to link to all of them, so below, I’ll provide a list of the routes that are serviced by the Ximen Station Bus Stop. I highly recommend travelers make use of the Taipei eBus website, or download the Bus Tracker Taipei app on your phone (Android | iOS) or use the Real-Time Bus Tracking service offered on the eBus website.

Here are the following routes that service the station: #9, #12, #49, #202, #205, #206, #212, #232, #246, #249, #250, #252, #253, #260, #262, #304, #307, #310, #604, #624, #660, #667, #662, #667

Similar to the MRT above, the park is a short walk from the MRT Station and Bus Stops.

Youbike

If you find yourself riding around town on one of Taipei’s shared bicycles, you’ll be happy to know that there is a Youbike docking station conveniently located next to the park. You can simply dock your bike there when you arrive and get another one when you leave.

Despite what little remains today of one of Taipei’s most elegant Japanese-era temples, the park offers a fitting memorial to what once stood on the grounds, and the usage of space, whether its the museum, tea house, bell tower or the exhibition space, was carefully considered. While it’s highly unlikely that the historic temple will ever be reconstructed, the park remains a pretty cool natural space within one of the hippest parts of the city and offers a nice respite from the hectic shopping areas of Ximen.

There is a long list of public events that take place in the park throughout the year, so if you’re visiting for the first time, you can enjoy the beauty of the bell tower and learn about the city’s history in the museum. For those of us lucky enough to live in Taiwan on a long-term basis, the park is an excellent place to visit throughout the year, depending on what exhibitions or events are taking place.

References

西本願寺 (臺北市) | 本願寺台湾別院 (Wiki)

Nishi Hongan-ji (Kyoto) | 西本願寺 | 西本願寺 (Wiki)

西本願寺(鐘樓、樹心會館) (臺灣宗教)

西本願寺(鐘樓、樹心會館)(國家文化資產網)

臺北西本願寺 (國家文化記憶庫)

西本願寺,我只知道名字,並不是很了解它的歷史。直到前一陣子在Pinterest找資料時,無意間發現一張日據時代的照片 (Nisa Yeh)

西本願寺:古蹟暨歷史建築調查研究及修復計畫 (台灣記憶)

The Legend of Hsimenting (台灣光華雜誌)