With the recent re-opening of the Taihoku Railway Bureau in Taipei, there has been a renewed focus around the country with regard to the history of the railway, especially when it comes to anything remaining from the Japanese Colonial Era.

After a long period of restoration, (likely requiring an obscene amount of money) both the headquarters of the former Japanese-era railway and the Taipei Railway Workshop reopened in 2020, attracting quite a bit of attention from the local media, nerds like myself, and tourists alike. That being said, even though Taipei is home to these two important historic sites, it most certainly wasn’t the first area in Taiwan to restore and reopen historic railway-related buildings to the public.

During the colonial era, the Japanese Colonial Government strategically set up Railway Bureaus and Workshops around the island in order to better maintain the operation of the continually expanding railway network that sought to eventually encircle the island. So, even though the headquarters was technically located in the capital, there were also large branch offices and workshops located in Kaohsiung to the south and Hualien on the east coast.

Today, the Kaohsiung Railway Bureau has been (高雄鐵道部) reopened as the “Hamasen Railway Cultural Park” (哈瑪星鐵道文化園區) while the Hualien Railway Bureau (花蓮鐵道部) is currently home to the “Hualien Railway Culture Park” (花蓮鐵道文化園區), both of which having reopened well before the park in Taipei!

So uh…. Take that Taipei!

Given that I’ve already introduced the Railway Bureau headquarters as well as the Taipei Workshop, I’m going to continue expanding on the subject with this article by introducing the former Hualien Railway Bureau and the Culture Park that exists there today.

Before I start, I think it is important to keep in mind that both the Hualien and the Kaohsiung Railway Culture Parks are much smaller in comparison to the one in Taipei. They were also reopened a lot earlier and likely didn’t receive a proportionate amount of funding as the one in the capital.

I’m not telling you this to lead you to think that they’re not as impressive. They’re still pretty cool.

I just think it’s important to remember that the scale and the exhibitions you’ll find at each of these parks is going to differ slightly. Likewise what you can see and do at each of them is going to be different, especially in the case of this park as it is often used by local vendors as an art space and a place for film festivals, etc.

Without further adieu, I’ll start by introducing the history of the Hualien Railway Bureau, then move on to its architectural design and then introducing about the culture park that exists there today.

Hualien Railway Bureau (花蓮鐵道部)

When the Japanese took control of Taiwan in 1895, a rudimentary railway in the Northern portion of the island had already been constructed between Keelung and Taipei. To slow the pace of the Japanese army’s advance into the capital however that railway was sabotaged in several sections, forcing the army to make quick repairs in order to ensure that they could effectively take administrative control of the capital.

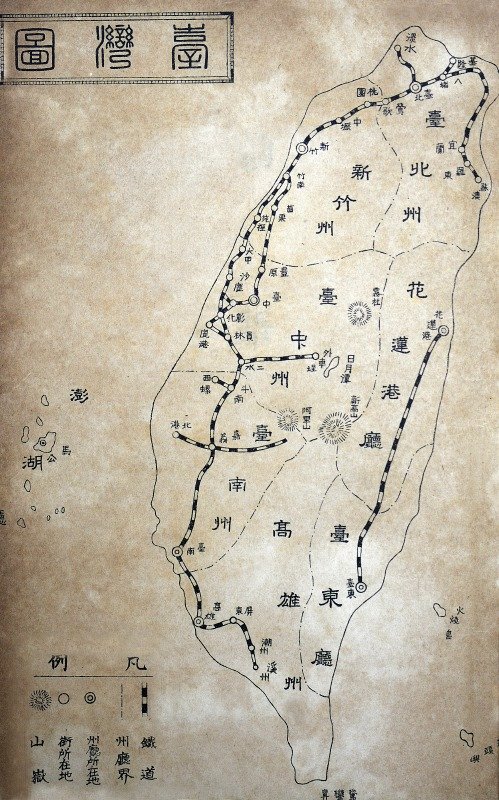

The sabotage scheme ultimately had little effect on the army’s advance with military engineers completing emergency reparations on the rail line and having it back in service within two months of their arrival. The “Temporary Taiwan Railway Team” (臨時臺灣鐵道隊) of engineers were initially stationed in Keelung, and by 1896, proposals were drawn up to improve and re-route the existing railroad between the port and the capital, while also making plans for a railway that would encircle the entire island.

By 1897 (明治30年), engineers from the Railway Team had criss-crossed Taiwan and came up with proposals for five routes that would stretch across the island, and were even considering an ambitious vertical route that would cross the Central Mountain Range. Unfortunately for the Railway Team, their exploration of the mountainous areas put them in direct confrontation with the Indigenous peoples near Taroko, resulting in the deaths of fourteen of their engineers, and the decision that a railway through the mountains wasn’t feasible.

In 1899 (明治32年), the ‘Temporary Railway Team’ was officially reestablished as the “Ministry of Railways of the Governor Generals Office of Taiwan” (臺灣總督府鐵道部), charged with managing the construction of a railway network around the island in addition to the operation and maintenance of public and private railways.

Note: The Private Railways mentioned above were those used by the various monopoly industries such as the camphor, sugarcane, coal, etc. Which were using branch railways off of the main lines to extract natural resources, and get them to port as efficiently as possible.

While the construction of the railroad along Taiwan’s much more developed western coast progressed rather smoothly, the Eastern branch line (臺東線) was a more difficult undertaking, and ended up taking considerably longer to complete. With railway construction simultaneously taking place in different stages around the island, the eastern branch line was completed several decades after the west coast lines.

For the purpose of this particular article, it’s important to note that construction on the northern segment of the line, from Karenko (花蓮港) to Poshiko (璞石閣), known today as Hualien (花蓮) and Yuli (玉里), started in 1909 (明治42年), and was completed in 1917 (大正7年).

The Eastern Branch ultimately wouldn’t be completed until 1926 (昭和元年) when 171.8 kilometers of rail was officially opened to the public between Hualien and Taitung, both of which were the terminal stations for the rail line.

Even though the Western Coast of Taiwan was connected by railway from Taipei all the way to Pingtung with more than a dozen branch lines between the mountains and the ports on the coast, service on the East Coast was considerably less convenient, with the line from Taipei terminating in Su’ao (蘇澳), Yilan’s southern most village.

It’s important to note that while there were plans to connect the Eastern Branch railway in the north between Yilan and Hualien and in the South between Taitung and Pingtung (屏東), as it is today, those plans were never actually realized.

Maybe that was a good thing though, at the time a trip between Taitung and Hualien took between 7-8 hours for passengers, and 11 hours for freight.

To coordinate operations on the Taitung Line, it was necessary to construct a Hualien Branch of the Railway Bureau (鐵道部花蓮出張所). Established in 1909, the Railway Bureau took up a prominent portion of the downtown core of Hualien, extending well-beyond what has been preserved today to encompass several city blocks. Featuring a Branch Office (出張所 / しゅっちょうじょ), Engineering Works (公務 / こうむ), Military Police Outpost (警務處 / けいむ), Inspection Garage (檢車庫), Water Stop (蒸汽火車加水塔), machine factory (機廠), official residence (處長官邸), staff dormitories (員工宿舍區), railway hospital (鐵道醫院), etc.

From 1909 until the 1970s, the Railway Workshop area was one of the most commercially active in downtown Hualien, and was constantly bustling with activity as it became one of the focal points for development and local administration.

This was in part due to the fact that a year after the Railway Workshop started operations, the Karenko Railway Station (花蓮港停車場 / かれんこう) was constructed next door and started limited railway service along the eastern line.

Note: The Hualien Railway Station has since moved to another part of town, but was originally located at the intersection of what has become Zhongshan Road (中山路) and Chongqing Road (重慶路) today. The station was constructed in 1910 (明治43年) and remained in service until 1981 (民國70年), it was torn down a decade later in 1992 (民國81年).

Even though the Hualien Railway Bureau dates back to 1909, the buildings that that we can visit today aren’t what you have seen when it was officially opened. What has been preserved as part of the railway culture park today date back to a 1932 (昭和7年) rebuild and expansion of the railway bureau which was a reflection of the completion of the eastern branch of the railway a few years earlier.

After 28 years of painstaking construction, the 173 kilometer Taitung Line Railway was completed and the start of operations coincided with the celebrations of the first year of the Showa Era (昭和元年). The official opening ceremonies for the completed railway were held on March 25th, 1926 and ushered in a new era of prosperity for Hualien, and the rest of the eastern coast of Taiwan as the flow of materials became much more efficient.

Similarly, given that the Hualien Railway Station was located next to the Railway Bureau, the area surrounding the railway became instrumental for economic development.

When the Second World War came to a conclusion and the Japanese surrendered to the allies, control of Taiwan was (ambiguously) given to the Republic of China (中華民國) and after Taiwan’s so-called “retrocession”, the Hualien Railway Bureau was occupied by the new regime, and renamed the Hualien Management Office of the Taiwan Railway Administration (台灣鐵路管理局花蓮辦事處). The buildings and equipment onsite remained in use until the early 1980s when the administration and maintenance of the railway of the eastern branch migrated across town in conjunction with the new station.

The current Hualien Railway Station, located north-west of the original station was recently expanded and underwent a several year period of reconstruction. Like its much earlier predecessor, the beautiful new station has become one of the focal points of the city, and as was the case in the past, the administration of the railway takes place within the upper offices of the railway station while the maintenance of the trains is taken care of at the massive 34,000m² Hualien Machine Factory (花蓮機廠) nearby.

Even though the original railway that ran through the port area of Hualien has been abandoned, parts of the track have been preserved and you can still see some of it along the the Old Railway Walkway (舊鐵路行人徒步區), which has been transformed into a hip part of town and a tourist attraction in its own right.

With the Japanese-era Hualien Railway Station having already been sadly torn down a few short years after the migration of the railway and its administration took place, experts, scholars and local citizens started to advocate for the preservation of the historic Railway Bureau, and the various buildings that still existed on the site.

In 2002 (民國91年), the Hualien County Cultural Affairs Bureau (花蓮縣文化局) officially registered the Railway Bureau and the various buildings on-site as protected historic buildings (花蓮縣歷史建築), and plans were made to restore the buildings and reopen them to the public as a culture park.

In 2011, restoration work on the first section of the former Railway Bureau was completed with the Branch Office (出張所) becoming the main attraction, while the dormitories and Machine Works across the street remained a work in progress. As of writing, this section has yet to be completely re-opened to the public. Likewise, the former Water Stop and Directors Residence are still undergoing restoration, meaning that I’ll have to return in the near future to check them out.

When I do visit again, this space will be updated, although I plan on dedicating an entire article to the Directors Dormitory, as it looks to be one of the prettiest of the high-ranking dorms that remains in Taiwan today.

Sadly, even though the Railway Hospital (舊鐵路醫院) has been protected as a historic property, restoration work on the building had yet to start before being partially destroyed by fire in early 2021. The damage to the historic buildings was considerable, and reparations will be funded by the Taiwan Railway Administration, but currently planning for the project is just getting underway, so we probably can’t expect that it will be part of the larger Railway Bureau Park any time in the near future.

Link: 花蓮舊鐵路醫院遭祝融 部分歷史建物受損 (UDN)

As mentioned earlier, the Hualien Railway Bureau certainly isn’t as large and thus far hasn’t been adapted into a well-organized culture park as its contemporary in Taipei. It has nevertheless become an important cultural and tourist attraction in Hualien, and over the next few years as the restoration process progresses, it will continue to grow, making it one of the focal points of cultural preservation in downtown Hualien City.

Hualien Railway Culture Park (花蓮鐵道文化園)

The Hualien Railway Culture Park currently consists of two sections that are open to the public, and feature historic exhibitions in addition to offering event spaces and allowing for private vendors to set up weekend markets and food stalls. There is a little something for everyone who visits the historic culture park, making it a popular tourist attraction for every type of tourist.

Below, I’ll briefly introduce both sections of the park, known simply as “Section 1” (一館區) and “Section 2” (二館區), explaining a little about each of the buildings within, their architectural design and what they’re currently used for within the contemporary culture park.

Section 1 (一館區) - Branch Office (出張所)

Section One of the Hualien Railway Culture Park is home to none other than the Railway Bureau itself. Essentially the most historically significant and architecturally distinct part of the park, this is where the everyday business affairs of the railway would have been carried out.

Home to the Branch Office (出張所), the building is a hodgepodge of architectural styles constructed with a fusion of Japanese and western elements, while also mimicking the traditional Chinese style four-sided courtyard (四合院) layout.

The front gates to the Branch Office open up into a tree-covered front courtyard with a drive way that would have allowed cars to come in and circle around on their way out. Directly to the left of the gate you’ll find a small Japanese-style guard building, which has amazingly served the same role from the day it was built until now.

On the opposite side, a bit closer to the front entrance of the Branch Office you’ll find a cement air-raid shelter that has been dug into the ground near one of the trees. The shelter is a relic of the Japanese-era, but was preserved in its original form - just in case.

The front courtyard is currently made available on weekends and holidays to local vendors who are permitted to set up tables to sell arts and crafts in addition to a variety of food trucks that offer snacks and drinks for sale to visitors. If you’re feeling hungry and feel like the food selection isn’t all that great, never fear, the Dongdamen Night Market (東大門夜市) is a two minute walk and there’s always something good to eat there!

The front entrance to the Branch Office is absolutely beautiful and is a long rectangular-shaped building with a double-layer roof. The center of the building opens up with a passageway covered by a gothic-style tower (哥德式高塔) that has stained-glass windows on all four sides, allowing for beautiful natural light in the corridor below. The tower is coincidentally one of the features of the building that makes the Branch Office so architecturally distinct and differentiates it from pretty much every other Japanese-era building remaining in Taiwan today.

Once you pass through the corridor you will find yourself in another beautiful courtyard surrounded on all four sides by the rest of the Branch Office. The courtyard has a little pond in the middle with some pine trees offering some shade.

Even though I just said that the layout of the Branch Office mimics that of a Chinese-style four-sided courtyard building, it does differ slightly and even though there are buildings on all four sides, they’re not physically connected in the way that a similar Chinese-style building would be.

The main area of the Branch Office is rectangular in shape and was home to offices on both the eastern and western wings. Once you pass through the corridor however, you’ll notice that there is a covered walkway on both sides that leads to the other buildings. The walkway that surrounds the building is what helps to make it look like the buildings are all physically connected, even though they aren’t.

Directly to the left of the corridor you’ll find another similarly long rectangular building that forms an “L” shape with the main building. These two buildings work together to make up the vast majority of the permanent exhibition space that provides historic information about the Railway Bureau.

Architecturally, both of the buildings are relatively similar in that they were constructed in the traditional Japanese ‘irimoya’ (入母屋) style, meaning that the base of the building is smaller than the roof, which extends beyond the base. The design of the roof on both of these buildings however is relatively simple compared to other buildings in this architectural style as they’re not of the typical hip-and-gable variety you’d see elsewhere. So even though the main building features the gothic tower that extends above the main part of the roof, the rest is quite simple.

The covered passageway that reaches around the building does make the roof appear as if its double-layered, but the purpose here was to prevent employees getting wet on rainy days and diverting the rain water onto the courtyard rather than the walkway, as well as allowing the various pillars that wrap around the building to evenly distribute the weight of the roof.

Both buildings have been constructed using wood and feature beautiful sliding glass windows on both the front and back sides, allowing for an ample amount of natural light into the building. This is important because the ceiling in the interior of the buildings is (currently) open, so you’re able to check out the intricate network of trusses that were put in place to help keep the heavy roof in place.

The building known today simply as Exhibition Area 1 (展覽區1) is the front facing building with the gothic tower was once home to the Directors Office (處長室), Administration Office (總務室), Works Department (工務課) and Maintenance Department (機務課). Separated into two different exhibition spaces, this building is essentially the main attraction if you’re interested in learning about the history of the Railway Bureau and the East Coast Railway.

Likewise, Exhibition Area 2 (展覽區2) is located in the wing directly to the left of the main building and was originally home to the Accounting Office (會計室), Traffic Safety Committee (行車保安委員會) and a Training Room (運務課). Today the building is home to a large model train version of Hualien City from the days when the Railway Station was located next door to the Railway Bureau. There are some other exhibition pieces in the building as well, but I feel like this is somewhat of a wasted space as they could probably do a lot more with such a large open area than having a model railway that doesn’t even run most of the time.

As I mentioned earlier with regard to how this Railway Bureau differs from the one in Taipei, wasted and unused space is an issue that the authorities have to deal with. Not only is the Exhibition Space in the former Accounting Building an underutilized space, the small electrical production building to the rear is likewise completely empty, while another one of the former offices at the rear of the courtyard are used simply for the park administration and public washrooms.

The most architecturally distinct building within the Railway Bureau is the former Meeting Room and Banquet Hall (聚會場所), a century old Japanese style building that was renamed “Zhongshan Hall” (中山堂) after the colonial era ended. Currently home to the Railway Movie Theater (鐵道電影院), the building was never actually planned to be utilized as an exhibition space, but instead a space where the Hualien City Government can hold film festivals. So when you visit, if there isn’t any events planned, you may find that the building is locked up and not accessible to tourists.

Constructed using local Hinoki Cypress (檜木) from Morisaka (林田山) and the Chinan Forest Area (池南林區) in the mountains of Hualien, the local government spent $11,000,000NT ($370,000USD) restoring the building, while retaining as much of the original cypress as possible.

Note: Morisaka (林田山) is known today as the “Lintian Mountain Forestry Culture Park” (林田山林業文化園區) while the “Chinan National Forest Recreation Area” (池南國家森林遊樂區) was located along the Haron Forestry Railroad (哈崙 (ハロン) 森林鐵道), two of Hualien’s three Japanese era timber railways.

In almost every article I’ve read about the building, it seems like they all parrot the same talking point, namely that ‘Zhongshan Hall’ is a century year old building. I thought it was a bit strange given that the rest of the Railway Bureau is around ninety years old (as of 2021), so I spent some time looking to see if the building was part of the original itieration of the Railway Bureau, but no one offered up any information as to why the building was being dated the way it was. After a while, I more or less just came to the conclusion that they were probably rounding up. The building appears like it was constructed at the same time as the rest of the buildings on site so we still have another decade to go before its reaches its centennial.

That being said, the Railway Bureau’s banquet hall is definitely the most elaborate in terms of its architectural design in comparison to the other buildings. Yes, it was constructed using hinoki cypress, one of the most expensive types of wood in Taiwan, but it also features the most elaborate roof. Even though the building doesn’t feature a traditional Japanese hip-and-gable roof, it has beautiful black Japanese roof tiles (黑瓦), which have recently been restored. It also features a lower second layer that extends entirely around the building and is held in place by a network of pillars. Similar to the covered walkways on the front buildings, this one has received a bit more attention in its design.

The last thing I’ll mention about the design of this building is its windows, there are large sliding glass windows on all four sides as well as rectangular-shaped windows above the first layer of the roof that allow natural light into the building. The lower sliding windows are of course quite common within Japanese architecture, but one thing you’ll want to pay attention to are the round dormer (oxeye) windows (老虎窗) on the front and back, which were pretty much only added for design purposes, but were popular for the more elaborate buildings of that era.

Oh, and the ox-tail windows are part of the reason why I’d argue that the building isn’t a century-old as they are an architectural feature that started appearing on buildings after the 1920s.

Section 2 (二館區) - Engineering Works

The recently opened “Section 2” of the Railway Culture Park is much smaller than the main section, but if you ask me is a little more interesting. Unfortunately though, while the restoration of all of the buildings in this sections seems to have been recently completed, some of them remain empty and severely under-utilized.

This will probably only be a short-term issue as they’ll certainly not allow their investment in the restoration of these buildings to go to waste. So, as I mentioned above, I’ll certainly have to be visit again to make sure that I have more photos of these buildings, especially of the interior!

This section of the Railway Bureau was considerably more functional than the other one, which mostly served an administrative purpose. Section 2 was home to the Engineering Works (工務段), and a police outpost (警務段), in addition to preserving part of the original railway that was used for the maintenance of trains.

Even though the buildings in Section 2 are yet to be opened to the public on a full-time basis, I have to say that I actually enjoyed my visit to this part of the Railway Park more than the other section. The reason for this is because the buildings are more traditional in their architectural design, and because the area is covered with beautiful trees, which have been growing there since the buildings were constructed almost a century ago!

Likewise, a couple of the buildings in this section have been opened up to private businesses, one of which currently has a Kimono rental place and another a really nice coffeeshop that has a couple of Shiba Inu’s who hang out in the area.

You’ll also find historic LDT103 steam locomotives on the rail tracks that you’re able to take photos with!

The various buildings on site are as follows:

Engineering Works (工務段)

Police Outpost (警務段 / 武道館)

Detention Building (拘役所)

Iron Works (打鐵工房)

Warehouse (附屬倉庫)

Air raid shelter (防空洞)

The first thing I’ll say about the section is that without its giant banyan tree (榕樹), I don’t think I would have enjoyed visiting as much as I did. The century-old tree provides both character and ambiance to the park, and the buildings that surround it should be grateful that they are able to bask in its glory.

The largest building in the park is the former Engineering Works (公務段 / こうむだん), which is now home to a popular coffee shop. The building was constructed in traditional Japanese architecture with Taiwanese wood and black roof files. The construction of the roof on this one is simple, but the sliding glass windows are quite beautiful. If you have the chance, make sure to go into the coffee shop to check out the interior of the building and enjoy a coffee.

Link: The role of Public-Private Partnerships in Conserving Historic Buildings in Taiwan

Across from the Engineering Works, you’ll find a small Air Raid Shelter dug into the ground near the banyan tree, which you can check out. This one isn’t as large as the air raid shelter in the other section of the park, but it is probably big enough to fit a dozen or so people.

Behind the banyan tree, you’ll find the former Iron Works (打鐵工坊), which retains some of the original equipment that was used for constructing and repairing rail lines. There’s not too much to see while inside the building, but it was a pretty important part of the Railway Bureau for quite some time.

Interestingly, when we approached the Police Outpost (警務段), I commented that the exterior looked a bit like what you’d expect from one of Taiwan’s smaller Martial Arts Halls (武德殿) to which I received the comment, “But it isn’t, its an old police station!” Well, I am to boast that I had the last laugh on that one because research on the subject says that prior to 1946, the building was used for practicing Judo (柔道) and Kendo (劍道). It was only after the Japanese left Taiwan that it was converted to a police outpost.

With that being said, near the former Martial Arts Hall / Police Outpost you’ll find a more recent addition, a cement structure that was used to hold prisoners on a short-term basis. The small jail (拘役所) is open to the public and its a popular place for people to take photos.

Unfortunately during my visit, both the jail and the former police outpost were closed and as I peered in through the windows, it looked as if the police outpost was emptied for some reason.

The final building on the site is at the rear of the park and in the past was simply used as a storage warehouse. That being said, it looks like all of the other buildings on the site as it was constructed with wood, sliding glass windows and Japanese architecture. Even though it is quite small, today it is occupied by a private company that rents kimono, yukata, and specifically tailored outfits that were popular during the colonial era.

This part of the park is also home to an old section of the railway where you’ll find one of the old steam engines and freight cars on display. The steam engine was especially brought by the Taiwan Railway Administration to Hualien to put on display here as this type of steam engine was the one that was used to bring prosperity to the east coast.

Getting There

Address: #71 Zhongshan Road, Hualien City

(花蓮縣花蓮市中山路71號)

GPS: 23.9721202 121.6130952

Located within the downtown core of Hualien, the Railway Bureau is a short walk from the city’s popular Dongdamen Night Market (東大門夜市) and is easily accessible through public transportation.

That being said, the Railway Bureau is actually not all that close to the current Hualien Railway Station, which is probably a 20-30 minute commute if you’re walking.

Car / Scooter

If you’re in Hualien and have access to a car or scooter, getting to the Railway Bureau isn’t all that difficult and there is an ample amount of parking in the area along the street or within the paid public parking lots near the night market.

Simply input the address or the GPS coordinates provided above into your preferred geolocation assistant and you’ll be there in no time!

Bus

Given that the Railway Bureau is conveniently located within close proximity to the tourist night market, you’ll find a number of public transportation options for getting there from various areas around Hualien. So, even if you’re not located next to Hualien Station, you should be able to find a bus that fits your specific needs.

Dongdamen Night Market Bus Stop (東大門夜市站)

Taroko Bus (太魯閣客運): #301, 307, 308

Hualien Bus (花蓮客運): #1123, 1126, 1128, 1129, 1131, 1132, 1133, 1136, 1139, 1141, 105

Xuanyuan Rd. Bus Stop (軒轅路站)

Ding-dong Bus (鼎東客運): #8119

While in Hualien, if you’re interested in similar Japanese era destinations, I highly recommend checking out the Hualien Martyrs Shrine (former Shinto Shrine), the Hualien Cultural and Creative Industries Park (花蓮文化創意產業園區), the Yoshino Shrine (慶修院), the Pine Garden (松園別館), the Hualien Sugar Factory Dorms (花蓮觀光糖廠), etc.

There is certainly a lot to see and do while in Hualien and you should never feel like Taroko Gorge and the Qingshui Cliffs are the only destinations to visit! The city is home to quite a few historic tourist destinations where you’ll also be able to enjoy yourself!

Hours: Tuesday - Sunday 09:00 - 17:00 (Closed on Mondays)

Unfortunately during my visit, quite a few of the buildings in both the First and Second Section in addition to the former Director’s Dormitory were not open to the public. In some cases it seems like they were in the process of changing exhibitions while others just weren’t open at all. So, as I mentioned a few times already, I’ll have to visit again to get more photos. When I do, I’ll update this space, but I’ll probably dedicate an entire article to the directors dormitory.

Nevertheless, the Hualien County Government has spent a considerable amount of money restoring the former Railway Bureau and even though some of its space is under-utilized, they have come up with some pretty good ideas for attracting locals and tourists alike with weekend markets, film festivals and coffee shops in the historic buildings.

Given the Railway Bureau’s close proximity to the popular Dongdamen Night Market, you can be sure that there will always be a steady supply of visitors coming to check it out! Even if this one isn’t as big on the historic displays of information, it is still a place where you can learn quite a bit about the important history of the railway in Taiwan, with a special focus on the east coast!

References

Hualien Railway Culture Park | 花蓮鐵道文化園區 (Wiki)

臺灣鐵道史 (Wiki)

花蓮鐵道文化園區 (花蓮綠活小旅行)

歷史沿革 (花蓮鐵道文化園區官方部落格)

花蓮舊鐵道商圈歷史與脈絡 (ArcGIS Online)

舊花蓮驛前碩果僅存的鐵道部出張所歷史建築 (獨立評論 @ 天下)

花蓮鐵道文化園區 (駱致軒)

修復半年 花蓮鐵道文化園區一館重新開放 (客家電視)

穿越百年鐵道時光!4處不可錯過的鐵道文化園區 (Newtalk新聞)

花蓮百年台鐵中山堂 擬打造鐵道電影院 (CNA)

Hualien 太平洋臨港歷史廊道文化導覽 (花蓮縣全球資訊服務網)

和風老屋旅行散策 (江明麗) ISBN: 978-9862487594