I know what you’re thinking!

“Finally, he’s posting an article that has nothing to do about the Japanese Colonial Era!”

“We’re finally going to get to read something about a popular tourist destination with some pretty photos that has nothing to do with history.”

C’mon. Don’t fool yourself.

You know I’ll find a way to mix the two!

Today I’m going to be introducing the famed Brown Boulevard in Taitung’s historic Chishang Village.

Keyword: Historic!

If you’ve been in Taiwan long enough, you’re probably familiar with the iconic Chishang Bento Box (池上飯包), which likely has more branches around the country than McDonalds.

While it should be obvious that these historic lunchboxes originated in Chishang, the better questions is to ask why are they so highly regarded?

The easy answer is because Chishang produces arguably the best rice in all of Taiwan.

Rice that is so awesome that it was apparently eaten by the emperor of Japan himself.

And thus, you probably see where I’m going to go with this one.

Chishang’s rice, Chishang’s bento boxes and all of what we’re able to enjoy today is a direct result of the five decades that Japan ruled over Taiwan and developed the island.

So before I start talking about Brown Boulevard, give me a few minutes to help you better understand how one of Taiwan’s most prolific agricultural industries got its start!

I’ll try to be brief, but let’s be honest, that’s never really been my strong point.

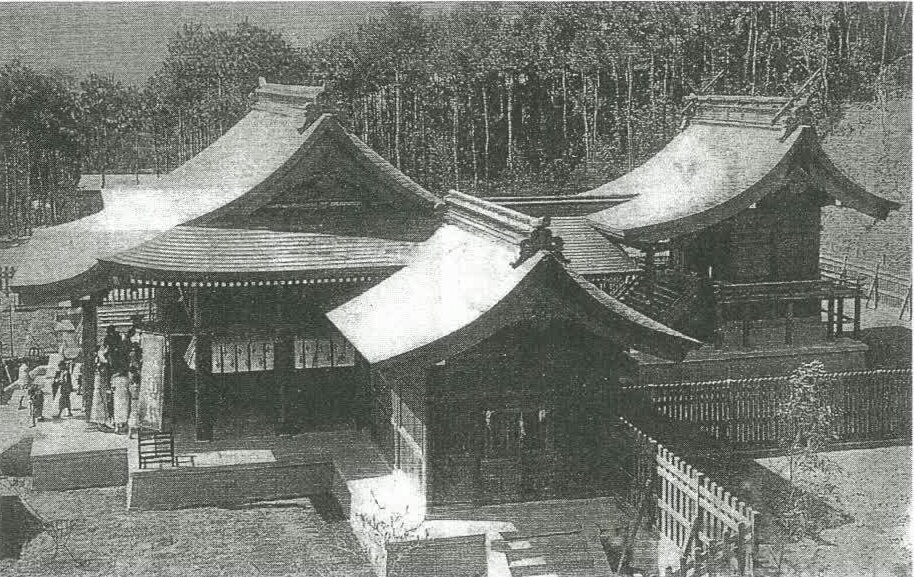

Ikegami Immigrant Village (池上移民村)

The Japanese Empire took control of Taiwan in 1895, and after a period of instability and heavy-handedness, life in Taiwan (for better or worse) eventually settled to become that of the model colony the Japanese were looking for.

For the first few years, the only Japanese citizens who came to Taiwan would have been predominately military, civil servants, engineers and business people who sought to capitalize on the treasures that the island had to offer the empire.

When the situation stabilized, the government made the decision to start a campaign to encourage immigration to the colony, which viewed further immigration to Taiwan by ‘ordinary’ (most often lower-class citizens), especially those who were laborers or farmers. This was perceived as not only a great way to improve production here in Taiwan but also dealing with pervasive issues back in Japan, where lack of land and opportunities were causing issues for the rapidly industrializing country.

Ultimately though, looking back through a historical lens, it is easy to see that mass immigration to Taiwan was a test for a ‘settler colonialism’ scheme in which Japanese citizens would mix with the local population, with the latter eventually being outnumbered.

The East Coast was chosen as the optimal location to start an immigration campaign for these ‘planned communities’ (移民村), due to the fact that it was sparsely populated and thanks to the ‘availability’ of land.

And to sweeten the deal, the government would provide each family with transportation, a home and a plot of land to farm on, in addition to a number of subsidies.

The “model immigrant community” project, officially lasted from 1909 until around 1918 and achieved relative success, but no where was it as successful as it was on the East Coast with Yoshino Village in Hualien acting as the model for nearby villages like Toyota (豐田), Hayashida (林田), Yoshita (賀田), Kano (鹿野) and more importantly for this article, Ikegami (池上).

Link: Huadong Valley Ride 2018: Hualien City to Fenglin (Spectal Codex)

Looking back, we can see that the hard work that went into developing the land used for these villages has helped to ensure that today, we continue to be spoiled with some of the best rice, vegetables and fruit in the world.

And there are few places where that is put on display more than in the former immigrant village of Ikigami, known today as Chishang (池上).

Ikigami Village, which is the Japanese pronunciation of “chishang” (池上), the name used today literally means “by (on) the lake”, referring to the nearby Dapo Lake (大坡池), which was instrumental in the irrigation system that was set up for the cultivation of rice in the area.

Note: Like many of the other immigrant villages on the east coast that I mentioned above, when the Japanese left Taiwan, the villages retained the same names, but were switched to the Mandarin pronunciation. Most English-speakers however fail to realize that “Fengtian” for example was the same “Toyota” as the cars!

Prior to the arrival of the Japanese, the land where Ikigami would eventually be established was home to the Amis (阿美族), who had migrated out of the area into Hualien in the early stages of the 19th century after an alliance of Siraya (西拉雅族) and Puyuma (卑南族), two of Taiwan’s Plains Indigenous groups (平埔族群) forced them out.

By the late stages of the 19th century, Emperor Kangxi (康熙) removed the longstanding ban on immigration (封山禁令) beyond the western coast of Taiwan. This prompted a wave of Chinese migration, who named the area “xin kai yuán” (新開園), which literally translates as “Newly Opened Land”, but even with a nice name like that, life really sucked for those immigrants who had little to no protection from malaria and other sicknesses let alone the constant threat of attack from the indigenous people.

It didn’t really matter very much though as a few years later, the Qing’s flimsy control of Taiwan came to an end after the First Sino-Japanese War (日清戰爭), resulting in the Treaty of Shimonoseki (馬關條約), and control of Taiwan and the Peng Hu archipelago being handed over to the Japanese.

As mentioned above, the Japanese arrived in Taiwan in 1895 (明治28年), but what I didn’t include was that after the signing of the treaty with China in April, the Japanese army arrived in Taiwan in May and by November of that year, they claimed to had accomplished what the Dutch, Spanish and Chinese could never do - they controlled the entire island.

That being said, complete control over the island probably didn’t actually take place until some years later as they faced resistance from indigenous groups as well as the Hakka and Hokkien people who had been here for years.

Once they did control the island though, they set out to develop it and start extracting all of its many resources.

It’s hard to know for sure how many indigenous and others were killed during the period of resistance to Japanese rule, but without a doubt, thousands perished in the process.

By 1909 (明治42年), the eastern immigration plan had been established and the model immigrant villages mentioned above started popping up along the east coast, with both public and private investments.

To facilitate the creation of an immigrant village in the ‘Newly Opened Garden’ area, an estimated 2,298 hectares (2,370甲) was reserved and was officially renamed “Ikigami Village” (池上村).

It’s important to mention that of the 2,300 hectares reserved for the village and agricultural production, the vast majority (2,143 hectares) of land was considered untamed wilderness (原野) while the rest was divided/developed into 55 hectares of dry farmland (旱田), 37 hectares of paddy fields (水田) and 7.5 hectares reserved for construction (建地) respectively. More on that later.

Note: 1甲 = 0.9699 hectares = 2,934坪 (甲 jia and 坪 ping are Taiwanese units of measurement)

With the Taitung Sugar Corporation (臺東製糖株式會社) charged with the development of the village and bringing in new immigrants, in 1913 (大正2年) construction on over two hundred houses started with land partitioned to ensure that each of the households could contribute to agricultural production.

Immigration to the area however didn’t start until 1919 (大正8年) when 49 families were brought to the area from Shinanogawa City (信濃川) in Japan’s Nagano Prefecture (長野縣).

Immigration slowly continued throughout the next few years, but the initial stages of the project (in addition to several of the other immigrant villages set up under the operation of the Taitung Sugar Corporation) came to a sudden end.

By 1921 (大正10年) the Taiwan Governors Office and the Bank of Taiwan became frustrated with the lack of success of the privately run company and stopped granting them loans. With mounting debts, the Taitung Sugar Corporation was forced to restructure its business operations leaving the newly formed Taitung Business Development Corporation (台東開拓株式會社) to focus on any lingering immigration-related business, while the rest of the company would focus solely on its most important function, the production and export of sugar.

Over the next few years, with continued attempts to fill the houses with immigrants from Japan failing, the company settled on bringing in a mixture of locals and Japanese to help populate the village and contribute to agricultural production. This attempt resulted in limited success as by 1926 (昭和元年) the Eastern Rail Line (東線鐵路) had reached Ikigami and the area near the newly constructed train station became a much more attractive place to live, in addition to being the centre of economic development.

Once the rail line had been completed, Ikigami became a much more attractive one and migrants, mostly Hakka’s from Hsinchu (新竹) and Miaoli (苗栗) started to pour in with the population surging over the next decade.

Ikigami ultimately failed as an experimental immigration village for Japanese citizens, but it succeeded in becoming a much more inclusive village than many of the other immigrant villages in that it was home to the Indigenous, Hakka, Hokkien and Japanese, all of whom worked together to create a paradise for the production of rice.

Later absorbed into the Kanzan Region (關山郡 / かんざんぐん) of Taito Prefecture (臺東廳), over the next few years, Ikigami Village would turn the failure of the immigration village into one of Taiwan’s most profitable and long-standing success stories.

One that has transcended the different eras of political rule over the island.

Gone were the days where sugarcane was the main focus of agricultural production as the people of the village worked to set up a sustainable system of rice cultivation that quickly achieved notoriety around Taiwan and especially in Japan where it was lauded as Tribute Rice (貢米), cultivated and provided directly to the Emperor.

When the Japanese arrived in Taiwan, they brought with them a Japanese grain of rice known as japonica (秈米) that replaced the earlier, longer grain (粳米) that was brought here by Chinese immigrants in the 16th century.

It took several decades before they actually learned how to successfully cultivate this special kind of rice in Taiwan’s temperate climates.

Link: Taiwanese Rice has its roots in Japan (Kyodo News)

By 1925, the colonial government was all-in on what became known as Ponlai rice (蓬萊米), a hybrid of japonica rice (ジャポニカ米) and Ikigami was geographically one of the most ideal locations to grow it.

Located within the area we refer to today as the East Rift Valley (花東縱谷), between the Central Mountain (中央山脈) and the Coastal Mountain ranges (海岸山脈), Ikigami is blessed with fertile soil and natural river water from the Xinwulu River (新武呂溪) in addition to the Dapo Pond which provides fresh water to the rice paddies.

According to locals, the secret to the success of Ikigami’s (Chishang’s) rice cultivation is in the following:

Excellent soil that contains clay and organic matter from the mountains.

Excellent water flowing from the mountain river and the pond.

Excellent weather and a climate suitable for agricultural production.

While there is certainly room for debate about the claims that Ikigami’s rice production was labelled Emperors Rice (天皇米), what is true of the rice production of the colonial era is that the vast majority of the spoils were shipped back to Japan.

So, as far as the locals were concerned, Ikigami’s rice may as well have been reserved for Japanese royalty.

Once again, even though Ikigami was a failure as an immigrant village, another area where it did succeed was in cultivating the massive amount of land that was reserved for the village into a viable location for agricultural production. It goes without saying that without the hard work of the immigrants, in conjunction with those from other parts of Taiwan, who joined them in converting over 5000 acres of land into a paradise for rice production.

Cultivation continues to this day and the quality of rice that is produced in Chishang is renowned throughout Taiwan, as well as overseas. The market however has since democratized, and even though rice is still exported to Japan, people from all over Taiwan are likewise able to enjoy the same quality of rice that was once ‘reserved’ for the Emperor.

While talking about the village, its history and its amazing rice, I’d be remiss not to mention the famed bento boxes (便當) that Chishang is known for. Whenever you go in Taiwan these days, you’re undoubtably going to find a Chishang Bento Box (池上飯包) franchise that sells lunchboxes to the starving masses of Taiwan’s work force.

Starting in the 1930s, shortly after the railway started passing through Ikigami, vendors would wait along the platform offering Sweet Potato Cakes (蕃薯餅) to weary travellers. This lucrative business later progressed into selling rice balls (飯糰) wrapped in peach leaves (月桃葉), which were the precursor for what we know and love today.

Note: Lunchboxes in Taiwan are known as “biàn dang” (便當), which is a word derived directly from the Japanese bento (弁当 / べんとう). When we use the words “fàn bao” (飯包) however, we are most often referring to the bento boxes inspired by the Chishang Lunchboxes.

Links: Even Train Rides Are a Chance to Eat Outrageously Well in Taipei (Eater)

The Biandang from Japanese Days to the Present (AmCham Taiwan)

As time went by, the rice balls evolved to include a variety of braised pork (滷肉), roast pork (烤豬肉), pork liver (豬肝) and lean slices of pork (瘦肉片) in addition to steamed cabbage, pickled radish, tempura and rice.

Then in 1962, the wrapped rice balls started being packed in wooden boxes transforming into the Chishang bento boxes what we’re used to today.

Even though you can enjoy a Chishang Bento Box pretty much anywhere in Taiwan, if you find yourself in Chishang, you will have certainly missed out on a great experience if you don’t take some time to enjoy one of the original bento boxes. So, if you are in Chishang, make sure to enjoy a meal at one of the following historic bento shops as you won’t find any of their vendors on the train platform these days.

Hometown Chishang Lunchbox (家鄉正宗池上飯包) #4 Zhongzheng Road 台東縣池上鄉中正路4號

Woo Chishang Lunchbox (悟饕池上飯包) #259 Zhongxiao Road 台東縣池上鄉忠孝路259號

Quanmei Chishang Lunchbox (全美行池上飯包) #1 Zhongshan Road 台東縣池上鄉中正路1號

And if you’re really interested in the history of these famed bento boxes, there’s a bento museum near the train station where you can learn all about their history.

Link: Chishang Bento Museum (Taitung Tourism)

Brown Boulevard (伯朗大道)

While excellent soil and fresh water are certainly important factors that contribute to producing Chishang rice, one might argue that the relatively low amount of pollution in the area also has an important hand in ensuring that the rice is always going to be some of the tastiest on the market.

Rice is grown in pretty much every city and county in Taiwan, but there are arguably few places as geographically distinct as Chishang, where factories are pretty much non-existent as they are in other areas of the country. This means that the rice enjoys the benefits of (relatively) pollution-free air in addition to the fresh mineral water and fertile soil provided by the East Rift Valley.

To ensure that this remains true for as long as possible, you’ll notice that the famed Brown Boulevard is devoid of all of the noisy cars, buses and scooters that you’ll find in other areas around the country. You’ll also notice that there is a distinct lack of street lights, electrical wires or telephone poles polluting the beautiful scenery. The vast fields are completely open and save for some roads running between the paddies, the area is completely natural.

The popular tourist attraction might just be one of Taiwan’s largest experiments in sustainable tourism, allowing the general public to enjoy the absolutely spectacular scenery of the vast rice fields, but only if they’re willing to do so by walking or on a bicycle.

Ironically, even though the rice fields have been around since the 1920s, tourism to the area has only really exploded within the past few years. These days you’ll find crowds of tourists walking or bicycling around the zig-zagging network of roads that criss-cross the paddies. This most often includes a mixture of families on vacation, couples walking hand-in-hand, and of course Instagram celebrities modelling for photos.

But, what happened to start bringing the massive crowds to the area? And how did the area become one of Taitung’s most popular tourist destinations? To figure that out, we need to take a look at the name of the place, “Brown Boulevard” or “Mr. Brown Boulevard” (伯朗大道).

The craze started when the local generic coffee company, Mr. Brown (伯朗咖啡) filmed a commercial on-site in 1992, bringing the area to the attention of the masses of domestic tourists looking for something to do with their free time. However, even though the area of town where the rice paddies are located has since been nicknamed “Brown Boulevard,” the Number One reason why so many tourists have been attracted to the area is arguably thanks to an EVA Air (長榮航空) commercial from 2014 that featured international sexy man Takeshi Kaneshiro (金城武) biking through the fields and enjoying some fresh tea under the shade of a tree.

Kaneshiro, who is a Taiwanese-Japanese actor can be seen in the final minute of the commercial promoting the beauty of Taiwan to the Japanese market, speaking Japanese with his iconic deep voice. Given the history of the area, Kaneshiro was probably the perfect person to help promote Taiwan as well as the Chishang area as he is able to bridge the gap between two countries as son of mixed heritage.

Did I mention that he’s beautiful? Just watch the video linked below. You’ll understand.

Link: Takeshi Kaneshiro Eva Air Commercial | Mr. Brown Coffee Commercial (Youtube)

These days, one of the most popular attractions on the boulevard is the tree where Kaneshiro enjoyed his tea.

The tree is referred to as the Takeshi Kaneshiro Tree (金城武樹) and even appears that way on Google Maps. You won’t need GPS to find it though, just look for where there are large crowds of tourists stopped to take photos.

While not exactly a “boulevard”, the network of roads running through the rice paddies is often described in Chinese as a “jade paradise” (翠綠的天堂路) thanks to the emerald-green rice paddies in a valley that is separated by two mountain ranges.

The thing you’ll want to keep in mind is that if you actually want to experience the emerald-green beauty of the boulevard, you’ll have to plan your visit wisely.

The best times of the year to visit the area are between May and June and October and December when the rice fields are growing. If you arrive too late in the season, the fields may have turned yellow with the rice close to being ready, or worse - having already been harvested.

If you can’t travel to the area during those times mentioned above, never fear. The place is beautiful all year-round.

While there, you’re probably going to want to rent a bicycle to ride around the fields, so if you’re looking for information on renting bikes, keep reading!

Getting There

Address: Brown Boulevard, Chishang Village. Taitung County (臺東縣池上鄉伯朗大道)

GPS: 121.21260 23.098776

Car / Scooter

If you have access to your own means of transportation, getting to Chishang is pretty simple.

You can either input the address or the GPS coordinates provided above into your preferred GPS system and it’ll map out your route for you.

What you’ll want to remember about driving a car or a scooter however is that you’ll have to pay for parking once you arrive at Brown Boulevard as both aren’t allowed to enter the pedestrian only area.

The car parks provided often operate as both a car park and a bicycle rentals, so if you plan on renting a bicycle to ride around the rice fields (which I recommend you do), you’ll be able to get a better deal on one of the bikes (electric or not).

The thing about the parking lots and the bicycle rental places being mixed together means that the prices or both are pretty standardized, but also allows for a little bit of tourist gouging.

These things certainly aren’t very expensive as per Taiwanese standards, but it’s unlikely that you’ll bother parking in one place and renting a bicycle from another, as that wouldn’t make much sense.

Be forewarned that if you decide that you’re smart and you’ll instead find parking somewhere along the road near the boulevard, it’s likely that you’ll have your car towed or you’ll get a ticket.

The whole thing seems like an organized tourist racket, so if you attempt to save a bit of money by not parking in a parking lot, you may find yourself paying a lot more in fines when your car gets towed.

Train

Taking the train is one of the easiest options for getting to Chishang as the station is served by not only the local trains (區間車) but also the faster Taroko (太魯閣), Puyuma (普悠瑪) and Tze-chiang (自強) express trains as well.

To get there, take one of the north/south bound trains on the east coast all the way to Chishang Station (池上車站). I probably don’t have to say this, but that would be a train headed north from Taitung Station (台東車站) or south from Hualien Station (花蓮車站).

Once you arrive at the station, the first thing you should do is stretch for a minute and then head directly to one of the famed Chishang Bento Box places to have something to eat before heading elsewhere.

From the train station, you have the option of taking a bus, taxi, bicycle or walking to Brown Boulevard, which isn’t all that far from the station.

Bus

If you’d like to take a bus to the area, you have a couple of options, but it all depends on where you’re starting from.

From Taitung to Brown Boulevard (台東轉運站 - 伯朗大道)

Ding-Dong Bus (鼎東客運) Mountain Line (山線): #8161, 8163, 8165, 8166

From Taitung Bus Station to Chishang (台東轉運站 - 池上)

From the Taitung Bus Station, you’ll want to hop on the Ding-Dong Bus Company’s Mountain Line (山線) bus and take it all the way to Chishang, which should cost about $160NT one way.

Link: Mountain Line Map | Fare Chart

From Chishang Train Station to Brown Boulevard (池上車站 - 伯朗大道)

From the train station walk out the front entrance and down the road where you’ll pass by the famed lunchbox vendors and onto Zhongshan Road (中山路), you’ll find the bus stop nearby. You’ll want to hop on Bus #8165 and take it to Brown Boulevard West Side. Or #8161, 8163, or 8166 in the other direction to the Jinyuan Stop.

Either way, the bus ride is about three kilometres and there are several stops for Brown Boulevard, so you’ll want to pay attention.

From Hualien to Chishang (花蓮 - 池上)

“Take Hualien Bus #1138”

If you’ve read other articles that say that you can take Bus #1138 to Chishang, you may want to ignore them.

This bus route hasn’t been in service for quite a while, and even then it was only from Fuli (富里), located in Southern Hualien county to Taitung Bus Station. It wasn’t really of any use for travelers coming Hualien city.

So, if you’re traveling from Hualien, I highly recommend taking a southbound train to Chishang and then transferring to a bus or walking from there.

Bicycle Rentals

It doesn’t matter if you arrive at either the western side or the eastern side of Brown Boulevard, there will be an ample amount of bicycle and parking vendors vying for your attention. As mentioned above, most of the rental places include the parking fee with the price of your bicycle rental, so you won’t have to worry too much about where you’re going to park your car or scooter.

The prices of bicycles tends to only vary slightly between the different outlets, but they don’t really differ all that much, so you can pretty much expect the following prices for bike rentals, which generally allow you to have the bikes for about two to three hours.

The great thing about the bike rental places is that they all have signs outside that clearly show their prices, which means you aren’t going to get taken for a ride when you arrive.

Remember though, the bigger than bike, the more expensive it will be - especially if its electric.

Single Person Bicycle (一人自行車): $100-150NT

Double Seat Bicycle (雙人自行車): $300NT

Four-Seat Bicycle (四人自行車): $500NT

Double Seat Electric Bicycle (雙人電動腳踏車): $500NT / two hours

Four-Seat Electric Bicycle (四人電動腳踏車): $800NT / two hours

As one of Taitung’s most popular tourist destinations, you can be sure that any time you visit Chishang and it’s Brown Boulevard that you’ll be doing so with large crowds of tourists. This is especially true during the four months of the year when the rice fields are full.

The area has become be one of Taitung’s most popular tourist attractions, but don’t worry - it’s large enough to share.

Walking or bicycling along the boulevard is probably one of the most amazing experiences you’ll have while visiting the East Coast, and all that exercise should probably make you hungry, so make sure to enjoy one of Chishang’s iconic bento boxes as well!

References

池上鄉 (Wiki)

伯朗大道 (Wiki)

池上飯包 (Wiki)

池上伯朗大道 (ZZTaitung)

日本移民村 (Encyclopedia of Taiwan)

『天皇米』之說的生成興再現 (邱創裕 / 國立臺灣師範大學台灣研究所)

從日本貢米到台灣香米 (Thinking Taiwan)

日本人的臺灣經驗~日治時期的移民村 (林呈蓉/淡江大學歷史系副教授)

台東第一打卡景點 竟是拍攝咖啡廣告的池上伯朗大道?(Line Today)

Taiwanese Rice has its roots in Japan (Kyodo News)

Mr. Brown Avenue | 伯朗大道 (Taitung Travel)

Chishang (Foreigners in Taiwan)