This post is a result of a combination of some long-time curiosity and my friend Alexander Synaptic rubbing off on me. I'm not very experienced with urban exploration, but hanging out with Alexander and listening to his stories has sparked an interest in the hobby. I've found that the more I learn about urban exploration the more I discover that the willingness to go into places (where you might not always be welcome) is similar to the courage that a successful street photographer needs.

It isn't easy walking up to a complete stranger on the street and taking their photo - Likewise with urban exploration you have to be willing to put yourself in a situation that brings you into unknown places and sometimes places where no one really expects you to be walking around. There is a level of respect however that both a street photographer and an urban explorer share with their subjects and that respect is typically shown with the stories that are told in the aftermath.

With street photography I feel like I've found that courage and even through I try to be stealth-like most of the time, I often still walk up to people, smile and point my camera in their face when something strikes me as interesting. Urban exploration on the other hand isn't as easy and in most cases with the kind of abandoned places people are quite suspicious as to why you want to check things out.

Today's exploration is an abandoned brick kiln (磚窯) found on a small road between Taoyuan's Longtan village (龍潭鄉) and Hsinchu's Guanxi township (關西鎮). I have been driving down this road for years (on my drives to Neiwan) and have noticed this place each and every time I have passed by, but until now never really thought to jump over the little fence in front of it and check it out.

Kilns of this variety were quite common in Taiwan several decades ago and helped to fuel the rapid development of the nation. If you're not sure what a kiln is, they are basically a thermally enclosed room that act like an oven. The insulation in the room helps to create temperatures that are sufficient for hardening or drying of clay objects and making them into bricks, pottery, tiles and other ceramics.

Despite a few wood-fire kilns of this variety still being active in the country (some just for show) most have been abandoned or replaced with more environmentally friendly versions which use natural gas and are able to produce bricks on a much larger scale.

There isn't much information available online about these particular kilns of which there are three. I've spent a lot of time searching the web, searching archives and searching PTT (a popular forum used in Taiwan) to figure out when they were closed, how long they were in operation and who owned them but not much of that information is available online, so I can't really tell you much. What info I could find online however is that the soil in the area is naturally sulphurous and was thus ideal for the brick-making process. This is why you can see three kilns in such a relatively close area.

The kilns are from separate companies named "Pacific" (太平洋), "Jianfu" (建富) and "Sanhe" (三合) which built them around year 60 on the Republic of China calendar (1971). They were built as Hoffmann Kilns (霍夫曼窯), a style introduced to Taiwan during the Japanese colonial period and are more popularly referred to here as "Bagua Kilns" (八卦窯) due to their resemblance to the Taoist "Eight Trigram" (八卦). Hoffmann kilns typically have a long tunnel, a main furnace and several different pits to make the bricks. The roof trusses make it seem like an octagon and that is probably where the resemblance comes up.

Huatan Hoffmann Kiln (花壇八卦窯) in Changhua, Taiwan (彰化)

These particular kilns were set up in that area when the Taoyuan sewer system was being constructed and were quite popular because the earth in that area was especially suited for brick-making. Information as to when the kilns were decommissioned or how long they were in operation isn't available online so it is hard to say with any degree of certainty how long they have been abandoned.

Reference: 磚窯(歷史遺跡) 仁安里第六鄰一帶的土質屬黃棕土,非常適合製造磚瓦。民國六十 年代初,有太平洋、建富、三合等多家磚窯。其中三合磚窯原是由內湖 搬至仁安里,這些窯屬於所謂的「八卦窯」,專門生產建築用的紅磚。所 謂「八卦窯」是一種類似隧道一般的窯洞,所不同的是窯內牆壁修飾成 八個斜坡面,看上去是八角型。他的最大特點是可以循環燒製磚胚,所 以產量比傳統的窯大很多。(Link /Pg. 47)

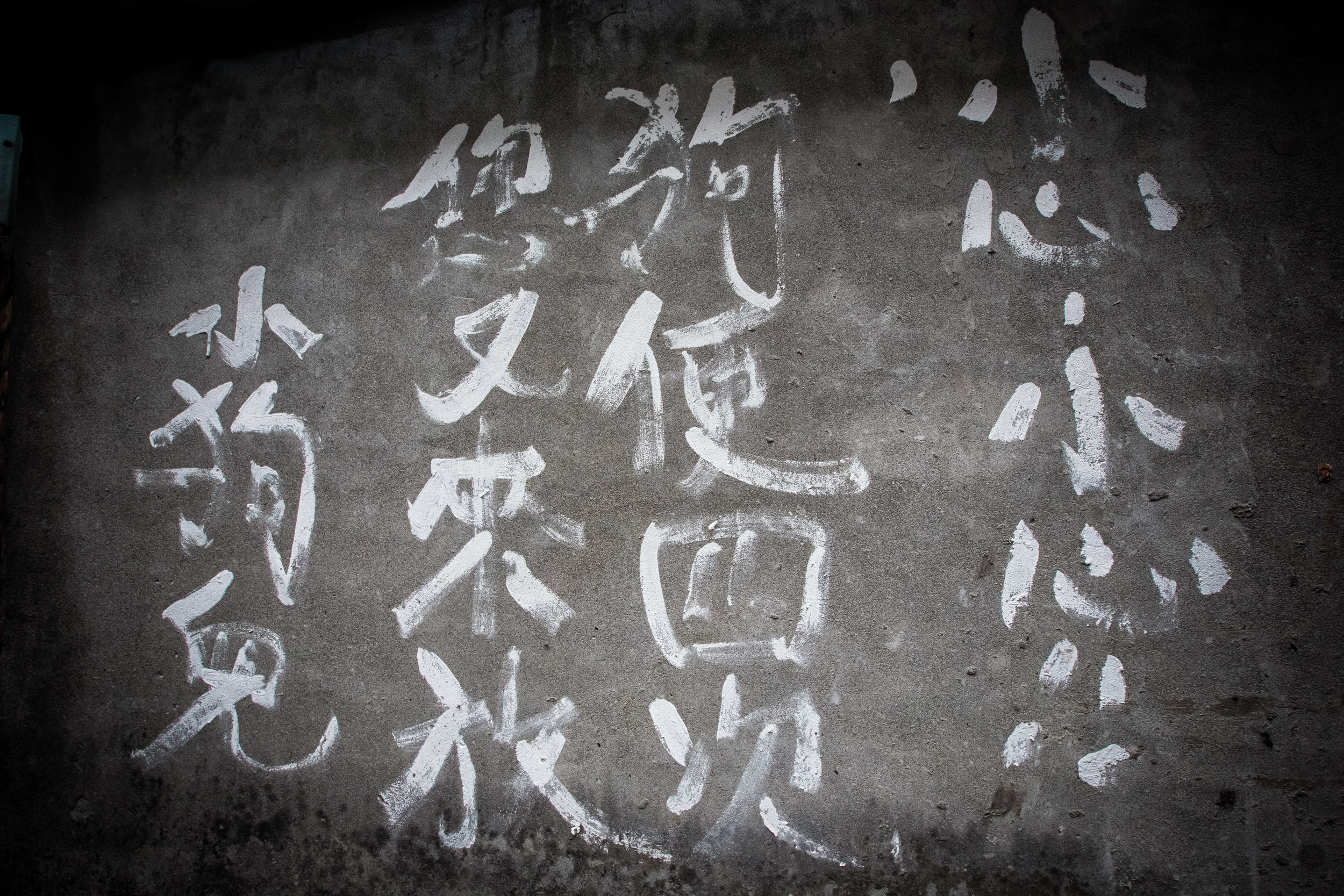

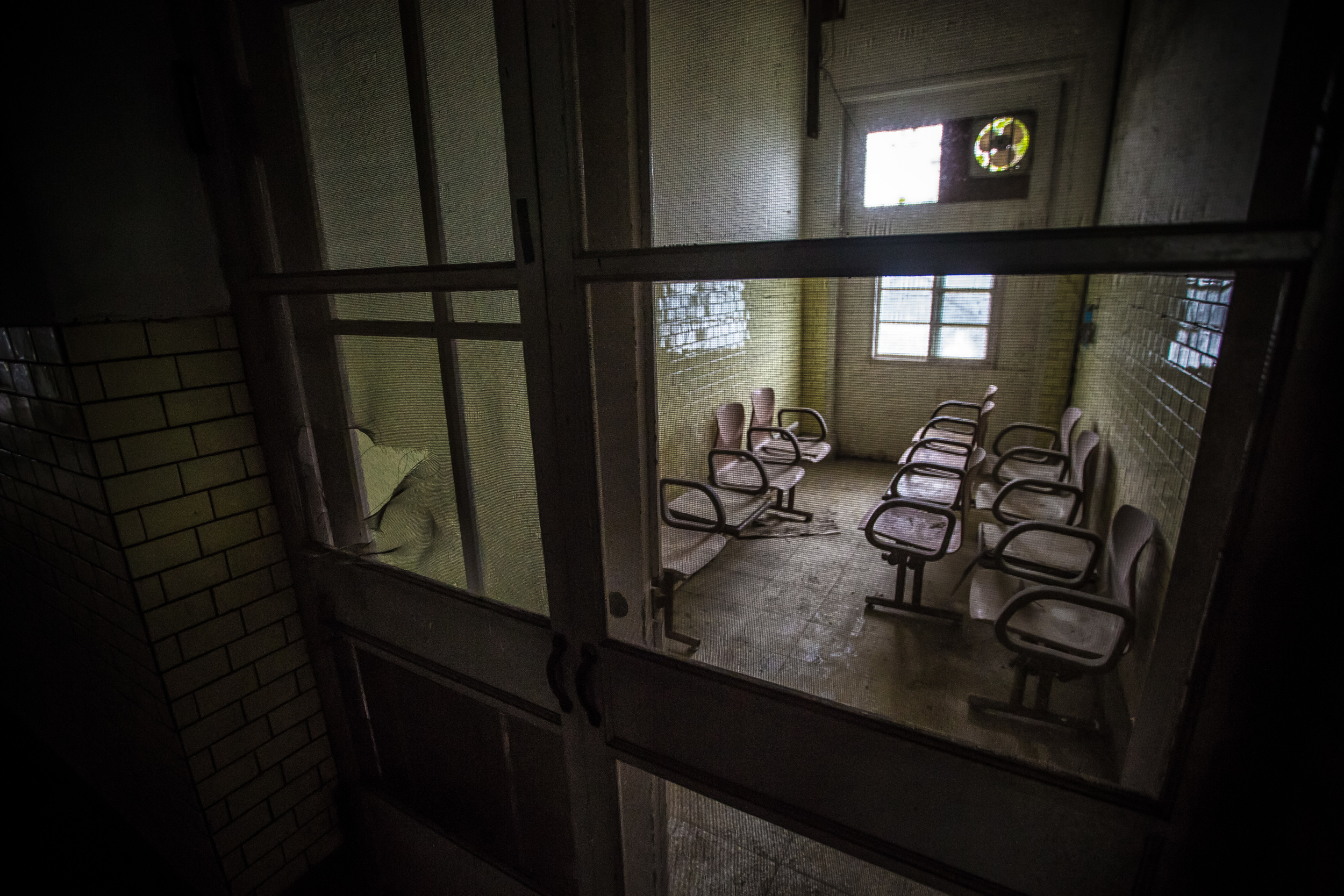

What I can tell you is what is still surviving today - The kilns sit alone in a large empty field near a Taipower generating station (龍潭變電所) off in the distance on one side and the popular Leofoo Village Amusement Park (六福村) on the other. There are three different kilns which were run by three different companies - one is close to the road, another is a short walk through a field while the third is a short drive from those two. There is also an abandoned building in between them that looks like it could have been a former office building. Unfortunately nothing was left inside the building to identify what actually went on while the place was in business.

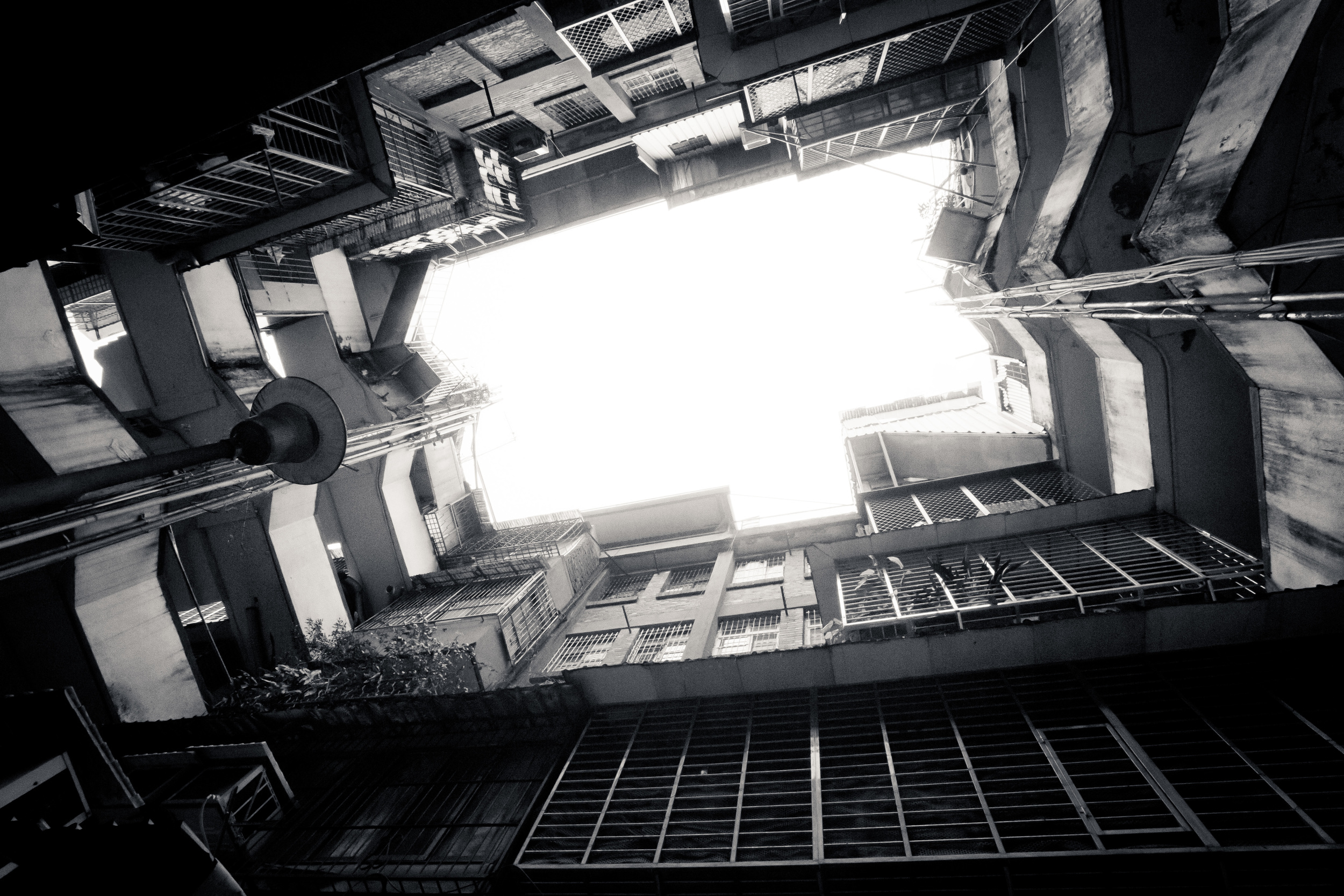

The kilns are somewhat similar in the fact that they have very tall (and well preserved) smoke stacks that rise out of what (from a distance) looks like a large mound of dirt. When you get close enough you'll notice that those mounds of dirt have been overrun with shrubbery and that in certain areas there are bricks popping out. There are several entrances to each of the kilns and on the inside there are several different furnace areas where they would have made the bricks. The inside of the kiln closest to the road seems like it has become a popular place for locals to dump some of their garbage making it a bit difficult and uninteresting to shoot.

Like a lot of abandoned places there are guard dogs on the grounds and they kind of prevented me from exploring too much. A group of five or six fully grown Taiwanese dogs aren't the type you want to mess with especially when you're on their territory. The funny thing about the dogs though is that when they had no idea I was around I saw them playing in the tall grass with each other and they looked like they were having a great time pouncing around.

As far as urban exploration goes, I'm not sure how this rates compared to what Alexander does, but there very little information available about these kilns available online in Chinese and none in English, so this is my contribution to their memory. The field they are in is really large by Taiwanese standards and it seems like a perfect location to build some dreary high rise apartments. I'm not sure how much longer they'll be around so if you're in the area check them out!

If you know any further information about the kilns or have any questions or comments, don't be shy. Comment below or contact me through the 'contact' section below.