This article has been a long time coming.

I’ve written extensively about Taiwan’s most important and architecturally distinct places of worship over the years that I’ve become a lot more selective when it comes to where I devote my time.

This is especially true considering that whenever I write one of these articles, I’ve discovered that it takes an incredible amount of time to complete one, and this one certainly wasn’t an exception to that rule.

I’ve written articles about some of Taiwan’s other significant Mazu temples in the past, but of the more than four to five hundred places of worship in Taiwan dedicated to the goddess, this one stands apart. With a history dating back more than three-and-a-half centuries, Tainan’s Grand Mazu temple is one of the nation’s most important places of worship, and one where you can list any number of superlatives to describe how significant it is with regard to Taiwanese history.

Originally the mansion of a ‘royal refugee’, the temple holds incredible religious significance as well as historic and political significance in addition to offering visitors a treasure trove of stone carvings, wood carvings, paintings, and historic relics. Thus, writing an informed guide about it certainly isn’t something that I could take lightly or finish quickly, so I hope for those of you reading this that you’ll be able to learn something that you might not have found elsewhere, while also enjoying the photos.

Tainan’s Grand Mazu Temple (臺南祀典大天后宮)

When discussing the history of Tainan’s Grand Mazu temple, you’ll often find articles and travel guides stating that the temple dates back to 1664, however, this is a claim that should be analyzed a bit more closely to better understand the temple’s history. While it is true that the building itself is that old, it wasn’t originally constructed to be a place of worship.

Constructed in 1664 (康熙3年), the building was originally a mansion provided for one of the seventeen remaining princes from the Ming Dynasty (明朝), who escaped to Taiwan when the Manchurian’s seized control of China and started the Qing Dynasty (清朝). Taiwan (or at least the greater Tainan area) at that time was controlled by a group of Ming-loyalists who had set up a military government known as the Kingdom of Tungning (東寧王國), under the leadership of Zheng Cheng Gong (鄭成功), who is better known as Koxinga.

The princes, who are often referred to by historians as ‘pretenders’ were a group of distant relatives of the Ming royal family who figured they had a claim to the throne if the Ming Dynasty (明朝) were ever to be successfully restored. However, that was rather unlikely given that the best the Zheng family could do was periodically attack coastal communities in Southern China from their bases in Taiwan and Peng Hu (澎湖).

One of the most important of the seventeen princes who fled to Taiwan, Zhu Shugui (朱術桂), who was given the formal title ‘Prince of Ningjing’ (寧靖王) resided in the mansion from 1664 until his death in 1683.

Constructed next door to a mansion for the Prince of Yanping (南明延平王), the son of Koxinga, who from 1662 was the ruler of the Kingdom of Tungning, it was important for the legitimacy of the Zheng’s to maintain the struggle to ‘restore the Ming’ for propaganda purposes, but they weren’t interested in sharing political power with the ‘pretender princes’. So even though they may have been afforded mansions like this one during their years in Taiwan, they were essentially just puppets for the pirate-kings.

1. The Prince of Ningjing (明寧靖王) was a prince with royal connections to the Southern Ming Dynasty (南明) in China while the Prince of Yanping (南明延平王) was simply a Prince of the short-lived ‘Kingdom of Tungning’ here in Taiwan, with no official connections to royalty back in China.

2. Similar to the Grand Mazu Temple, the mansion that was once home to the Prince of Yanping, the son of Koxinga is now occupied by Tainan’s God Of War Temple (臺灣祀典武廟) and a visit to one of these should temples should also include the other.

When Manchurian-led Qing authorities had finally had enough of the pirate raids and attempts to restore the Ming, Admiral Shi Lang (施琅) was given a mission to set sail for Taiwan and put an end to the Zheng family and their headache inducing attempts to cause problems for the newly established dynasty.

In the summer of 1683, Qing forces sailed to Peng Hu (澎湖) and defeated the Zheng family’s largest army. With the vast majority of their military power decimated, the leadership of the Kingdom of Tungning was left in disarray and the Zheng’s quickly surrendered bringing the Tungning-era to an end.

Seeing the writing on the wall, the Prince of Ningjing came to the conclusion that it would be best to end his life prior to the arrival of the Qing forces in Taiwan to save himself from whatever they had in store for him. Prior to his death, the prince’s five loyal concubines came to the decision that if their ‘prince’ was going to die, then so were they, so they hung themselves within the mansion. The next day the prince followed suit and ended his life in the same way.

Initially, I thought it was odd that the women killed themselves first, but later found it interesting to note that the prince made sure that they were properly buried in a tomb nearby (the site of the current Temple of the Five Concubines 五妃廟), and once that was done he took his own life.

One of the stipulations in the official suicide note (and/or last will and testament) left by the prince was that his mansion be converted into a temple dedicated to the worship of Guanyin (觀音), the Buddha of Compassion, and for a short time that was the case. Within a year of Admiral Shi Lang’s arrival in Taiwan however, the mansion was converted into a place of worship dedicated to the Hokkien Goddess of the Sea, Mazu (馬祖), transforming it into the first (officially sponsored) temple dedicated to her worship in Taiwan.

In 1684, the Taiwan Fu Princess of Heaven Temple’ (台灣府祠天妃宮) was established within the building, but in the same year Emperor Kangxi (康熙帝) bestowed upon Mazu the official titles “Empress of Heaven” (天后) and “Holy Heavenly Mother” (天生聖母), and the temple was renamed, officially becoming the first place of worship with the title “Empress of Heaven Temple” (天后宮), for which many would follow.

As mentioned above, there are hundreds of temples dedicated to Mazu in Taiwan today and as the Patron Saint of Taiwan, you can find several “Empress of Heaven Temples” around the country. Nevertheless, as this one was first of its kind, the Tainan temple became known (literally) as the ‘big’, ‘great’ or ‘grand’ Empress of Heaven Temple (大天后宮), ensuring its place in history, and it’s position at the top of the hierarchy of temples is maintained.

Long story short, even though the original building was constructed in 1664, the Mazu temple wasn’t actually established until a couple of decades later - In the grander scheme of things, twenty years probably doesn’t really matter very much to this three-and-a-half century old building, but it’s important to be clear with these things.

Obviously, as one of Taiwan’s oldest places of worship, it would be difficult to write out a concise history of all of the important events in paragraph form, so instead I’m going to offer a brief timeline of important events so that you can have a better understanding of its history.

Temple Timeline

1664 (康熙3年) - Zheng Jing constructs a mansion for the Prince of Ningjing (寧靖王朱術桂府邸), otherwise known as Zhu Shugui (朱術桂) a distant member of the Ming Dynasty royal line who came to Taiwan (along with more than a dozen other princes) hoping to restore the dynasty with the help of the Kingdom of Tungning (東寧王國).

1683 (康熙22年) - When Admiral Shi Lang (施琅) conquered the Peng Hu islands with a mission to continue on to Taiwan to put an end to the Ming Loyalist Kingdom of Tungning, the Prince of Ningjing realized that the Ming Dynasty would never be restored and decided to commit suicide. Before his death, his five concubines hung themselves one by one within the palace and then the next day the prince dressed in his royal attire and followed them in death. Prior to his death, the prince decreed that the palace should be dedicated to Guanyin, the Buddha of Compassion.

1683 (康熙22年) - Zheng Keshuang (鄭克塽), the Prince of Yanping (延平王), sent letters of surrender to the Qing forces stationed in Peng Hu, and the Kingdom of Tungning came to an end less than a month later with Admiral Shi Lang arriving in Taiwan on August 13th to receive the official surrender of the Zheng family and its army. Taken back to Beijing to have an audience with the Emperor, Zheng Keshuang was given the noble name Duke of Hanjun (漢軍公), and his army was absorbed into the Qing army.

1684 (康熙23年) - Admiral Shi Lang initially converted the palace into the ‘Taiwan Fu Princess of Heaven Temple’ (台灣府祠天妃宮), but when Emperor Kangxi bestowed the titles “Empress of Heaven” (天后) and “Holy Heavenly Mother” (天生聖母) upon the goddess, the temple was renamed the ‘Grand Empress of Heaven Temple’ (大天后宮), becoming the first major place of worship in Taiwan dedicated to the worship of Mazu (媽祖), and coincidentally also the first of many places of worship around the world with the “Tianhou Temple” (天后宮) title.

1685 (康熙24年) - Admiral Shi Lang erects the ‘Steele of the Pacification of Taiwan’ (平臺紀略碑) at the temple, which is currently the oldest remaining stele in Taiwan.

1720 (康熙59年) - The temple is officially upgraded into a Sacrificial Rites Temple (祀典) and was given the responsibility of coordinating important worship events in the Spring and Fall of each year (春秋二祭), and the name of the temple was officially changed to “Sacrificial Grand Goddess of Heaven Temple” (祀典大天后宮).

1765 (乾隆30年) - The temple undergoes its first major renovation since Admiral Shi Lang converted the palace into a temple.

1775 (乾隆40年) - A decade after the first renovation of the temple, a second renovation and restoration project takes place, converting the historic palace into the layout that is currently used at the temple.

1818 (嘉慶23年) - A fire breaks out in the temple on March 16th causing a significant amount of damage, including the damage to the original Mazu statue. It would take at least two years for the repairs to be completed. Interestingly, the local government at the time was strapped for cash, so the responsibility for the reparation of the temple and its funding were commissioned by a group of merchants known as the ‘three suburbs of the city’ (府城三郊). Given that the statues in the main hall were under repair with the other parts of the temple, Chaotian Temple (北港朝天宮) sent a statue to the temple to take up residency on a temporary basis, creating a relationship between the temples that continues to the day with the Beigang Mazu Pilgrimage (北港朝天宮迎媽祖).

1895 (明治28年) - The Japanese take control of Taiwan and the group of merchants known as the ‘three suburbs’ met with economic difficulty, which in turn caused issues for the fiscal control of the temple. Nevertheless, the temple continued to prosper as the colonial government considered it to be an important place of worship for the local population.

1941 (昭和16年) - As a result the 'Kominka policy' (皇民化運動 / こうみんかせいさく) imposed by the colonial government in 1936, Japanese language, culture and religion were forced upon the people of Taiwan, leaving little room for local traditional religious practices. This coupled with the decline of the leadership group resulted in a period of decline for the temple where it fell into disrepair. It was at one point slated to be auctioned off, but the colonial government fortunately blocked the auction and left the temple as it was.

1946 (民國31年) - As a result of the Xinhua Earthquake (新化大地震), the temple suffered a considerable amount of damage, prompting a restoration project that converted the roof of the building into a double-eave roof, which is how it continues to appear today.

1985 (民國74年) - The temple is officially recognized as a First Grade National Historic Site (第一級古蹟), putting it on a short list of very important historic sites in Taiwan.

2004 (民國93年) - After three centuries, Taiwan’s humidity got the best of the Mazu statue in the main shrine with parts of it collapsing resulting in a period of restoration for one of Taiwan’s most important religious images.

Now that we’ve taken a look at the history of the temple, let’s take a look at each of the shrines within so that you can better understand what you’ll see when you visit.

The Shrines within the Grand Mazu Temple

Layout Map from the official Grand Temple Website.

As the temple expanded over the centuries, so did the number of shrines located within. What started out as a palace for a prince was converted into a temple dedicated to who would become one of Taiwan’s most important religious figures. For a temple of its size, it’s common to find shrines dedicated to other deities, but in this one, they’re carefully chosen to better reflect the importance of Taiwan’s first and arguably most iconic Mazu temple. Below, I’ll list each of the shrine rooms within the temple and which deities you’ll find in each:

Main Hall (正殿)

I’m not exaggerating when I tell you that I’ve visited hundreds of temples and shrines of all shapes and sizes. Yet, from my first trip to Tainan (well over a decade ago) until now, it doesn’t matter how many temples I’ve visited in between, the Main Hall of the Grand Mazu Temple is (as far as I’m concerned) the most beautiful shrine room in the entire country.

Not only is the Main Hall absolutely beautiful, most people don’t realize that it is also very historic - Sure, that probably seems like an understatement given that the temple dates back to the 1600s.

What few fail to take into consideration here though is that the main shrine is currently also the permanent home to some significant deities, who lost their homes (just like Mazu almost did) during the Japanese-era. Providing a home to these celestial refugees makes this shrine room considerably more significant than the number of years it has been around.

To the right of the Main Shrine (右龕) you’ll find a shrine dedicated to the Dragon Kings of the Four Seas (四海龍王), originally worshipped at the Fucheng Dragon King Temple (府城龍王廟), which was constructed in 1716 (康熙55年) and torn down during the Japanese-era.

Similarly, on the left of the main shrine (左龕), you’ll find the King of the Water Immortals (水仙尊王), who moved to his current location when his temple, the Water Immortal Temple (臺郡三郊水仙宮) was bombed by the allies during the Second World War.

Taking into consideration that both of the temples above were administered by the same group of merchants as the Mazu temple, it wasn’t a big deal for the statues to be welcomed to take up residence there. The Water Immortal Temple dates back to 1683 (康熙22年), which means that the five statues are probably just as old. Interestingly, the temple was later reconstructed, but the original statues remain in place at the Mazu temple today.

Link: 臺南水仙宮 | Shuixian Zunwang | 水仙尊王 (Wiki)

Within the shrine you’ll find five statues of the Water Immortal Kings, each of whom are historical figures that are somehow related to water, and are believed to protect people at sea, much like Mazu herself. The five figures are as follows: Yu the Great (夏禹), King Ao (奡王), Xiang Yu (項羽), Wu Xizu (伍員) and Qu Yuan (屈原).

Note: Qu Yuan is considered to be the inspiration for the annual Dragon Boat Festival that is celebrated annually in many parts of Asia.

Within the Main Shrine (正中) in the center of the Main Hall, you’ll find the star attraction, Mazu (天上聖母) in a display like no other - The shrine is large and beautiful with a number of smaller images of the goddess flanked by a giant golden statue.

Accompanied on either side by her loyal guardians the green-skinned All-Seeing General (千里眼) and the red-skinned All-Hearing General (順風耳) whose names translate literally as ‘Thousand-Mile Eye’ and ‘Wind-Following Ear’. The two generals keep their ‘eyes’ and ‘ears’ open for danger, working in tandem with Mazu to help protect people at sea.

You’ll also find a shrine dedicated to the Tiger General (虎爺將軍), one of my personal favorites.

The temple claims that the Mazu statue in the main hall is the largest in Taiwan at 5.45 meters in height and dates back to the Qing Dynasty. Crafted over three hundred years ago, the statue was constructed using the Quanzhou style of mixing clay and wood (泉州派泥塑佛像).

In 2004 (民國93年), one of the temple’s keepers discovered that after almost three centuries of Taiwan’s notorious humidity, the statue’s head had fallen off, resulting in a period of careful restoration on the statue.

It was during this period that three stone tablets were found encased within the body dating back to 1822, detailing another restoration of the statue and more importantly indicating that the statue’s face was once covered in gold foil (金箔貼鋪). By that time, centuries of incense left had her face blackened, so with this newfound knowledge, the restoration of the statue not only repaired the statue, but converted its blackened face back to its original golden color.

Whether you’re looking at the statue directly or from either the left or right side of the shrine, the detail in her face is absolutely beautiful and the expression on her face is calming, displaying the beauty of traditional Hokkien artistry. It goes without saying that this Mazu statue is one of the oldest in Taiwan, but it is also one of the most important religious statues in the entire country as well.

Rear Hall (後殿)

The Rear Hall is located directly behind the Mazu shrine in an area that has a traditional open roof where you’ll find a large incense cauldron that is used for each of the four shrines within the hall.

I’m going to separate each of the shrines below so that you have a better idea of what’s going on in this section as there are quite a few important deities here.

Prayer Hall (拜亭)

Located directly against the wall of the Main Hall, with their backs to Mazu, you’ll find three important figures within Taoism known as the Three Great Officials (三官大帝). These ‘officials’ are considered the highest of the celestial deities and answer only to the Jade Emperor (玉皇上帝) himself.

The three officials are the Heavenly Emperor (天官), the Earthly Official (地官) and the Water Official (水官).

Goddess of Childbirth Shrine (註生娘娘祠)

On the right hand side of the rear hall you’ll find a shrine dedicated to the ‘Goddess of Childbirth’, also known as the ‘Goddess of Fertility’ (註生娘娘), who is one of the most highly respected fertility deities in Chinese Folk Religion, especially for those hailing from the Southern Fujian region of China - where many of the first immigrants to Taiwan originated. Holding a notebook in one hand and a brush in the other, she is charged with recording the births of every household, and does her best to assist anyone having trouble having children.

Sitting next to her, you’ll find another Southern Fujianese goddess, “Ms. Linshui” (臨水夫人) - According to legend, Ms. Linshui was a well-known Taoist priest named Chen Jinggu (陳靖姑) who was elevated to the status of goddess after death. Known to the Hokkien people as a protector of villages, she is also known as the patron saint of women and children.

As an assistant to the Goddess of Childbirth, she acts like a spiritual mid-wife for pregnant women.

Sacred Parents Shrine Room (聖父母廳)

The middle shrine in the Rear Hall is referred to as the ‘Sacred Parents Shrine Room’, referring to the parents of Lin Moniang (林默娘), who would be elevated to goddess status as Mazu, the Goddess of Heaven or the sea (depending on who you ask). While it’s not entirely unique, it isn’t exactly common to find a shrine dedicated to Mazu’s parents, so this is a pretty special one.

There is a bit of confusion with the literature about the shrine room as some refer to it as a shrine just for her parents (聖父母) while others refer to it as a shrine for her parents and siblings (聖父母兄姐). I’d probably say the latter is probably true given that there are several statues there.

Another thing that makes this shrine special is that it also features ‘spirit plates’ (牌位) dedicated to some interesting figures. First, you’ll find one dedicated to the Prince of Ningjing (寧靖王之牌位), who committed suicide in the building. You’ll also find two more for Qing-era Prefectural Magistrates of Taiwan Jiang Yuanshu (蔣元樞) and his predecessor Cheng Cheng (成城).

Matchmaking God Shrine (月老祠)

The shrine on the left hand side of the rear hall is a popular and powerful one known as the Matchmaking God Shrine. You’ll find shrines and temples dedicated to the ‘Old Man under the Moon’ (月下老人) all over the country, but a few of them are quite as special in terms of their spiritual ability to help people find a significant other - The Matchmaking God at this temple is one of those where you’re likely to find lots of people praying for some help in matters of the heart.

Accompanying the Matchmaking God, you’ll also find some other important figures including the Earth God (福德正神), the God of Wealth (文武財神) and the Five Literary Emperors (五文昌帝君).

Together, this shrine helps to assist worshipers with affairs of love, finances, education, etc.

Suffice to say, it’s also one of the most important and busiest shrines in the temple.

Yuanchen Palace (元晨殿)

Located at the rear of the temple, and in a secluded corridor next to the garden is a shrine named Yuanchen Palace, dedicated to celestial deities from Taoism. Within the musty old shrine room you’ll find the Mother of the North Dipper (斗母星君), commonly known in Taiwan as ‘Doumu’ with the Sixty Dukes of Jupiter (太歲星君) surrounding her. The Dukes of Jupiter are more commonly known as the ‘Taisui’ (太歲) and are extremely important figures when it comes to traditional Chinese astrology, each representing the twelve signs of the Chinese zodiac, with five ‘dukes’ for each sign.

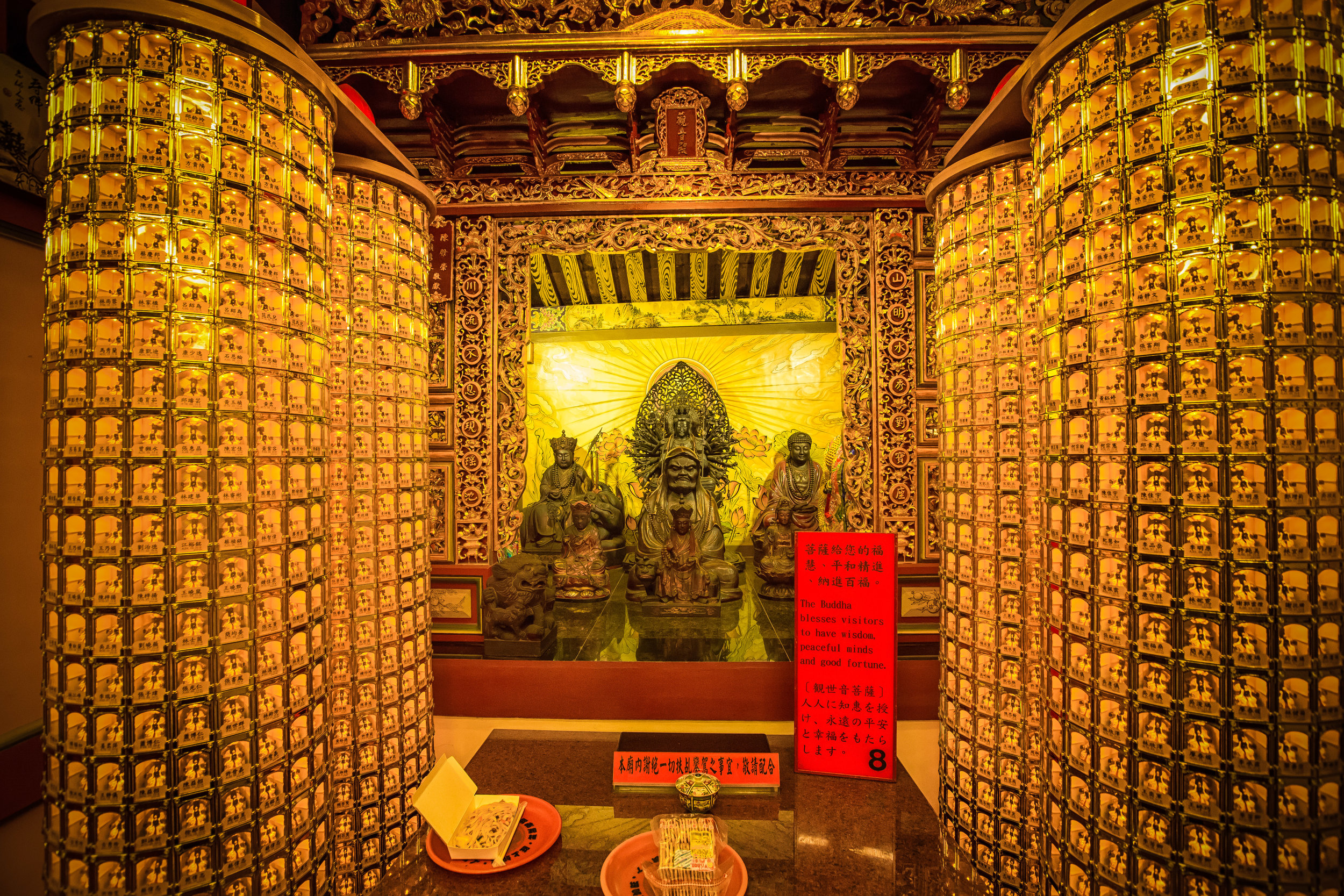

Guanyin Hall (觀音殿)

The location of Guanyin Hall was originally where the Prince of Ningjing’s personal quarters would have been. After he committed suicide, one of his dying wishes was that the main hall of his mansion be converted into a shrine for Guanyin, the Buddha of Compassion, while his quarters would be turned into a nunnery.

As mentioned earlier, when Admiral Shi Lang arrived in Taiwan, he converted the palace into a temple dedicated to the worship of Mazu, so the Guanyin shrine was relocated to the side hall where the quarters were originally located.

The statue of Guanyin is one of three historic statues dedicated to the goddess that was donated by the Qing-era prefect Jiang Yuanshu (蔣元樞), dating this particular statue to sometime in the late 1700s.

Similar to the statue of Mazu, at nearly 250 years old, it’s face has blackened over time with centuries of incense smoke staining her face.

Three Treasures Hall (三寶殿)

One of the ‘newest’ additions to the temple, dating back to the 1970s, the ‘Three Treasures Hall’ is a room dedicated to three of Buddhism’s most important figures. Within the main shrine you’ll find statues of Amida Buddha (阿彌陀佛), Shakyamuni Buddha (釋迦牟尼佛) and the Medicine Buddha (藥師佛), whom together are known as as the Three Treasures. Directly in front of them you’ll find a statue of Maitreya Buddha (彌勒佛), who is probably more well known among westerners as the ‘Laughing Buddha’ or simply just the fat one.

On both the left and right of the shrine, you’ll find two guardian deities, who often appear as protectors for the Buddha’s, or as ‘Door Gods’ (門神) in many of Taiwan’s temples. On the left you’ll find Skanda (韋馱) and to the right Sangharama (伽藍), who is simply the Buddhist version of Guan Gong (關公), a popular historical figure known as Guan-Yu (關於), who is highly regarded for his ability to offer spiritual protection and grant blessings.

Architectural Design

As is the case with the very few buildings of its age that remain in Taiwan, the Grand Temple has changed quite a bit over the years, with the interior design and layout of the building altered due to fire, or some of the other reasons mentioned above - So to describe the architectural design of the building, I’m going to look solely at its current layout, but I’m also going to spend some time introducing some of the important decorative aspects of its design as well as the historic objects you’ll find within.

The architectural design of the temple is officially described as a “relic of the Southern Ming Dynasty, and the only remaining Ming-style palace in Taiwan”. Even though the Ming Dynasty is fondly remembered for its architectural prowess (look no further than the Forbidden City), this mansion-turned-temple was constructed several years after the Qing took control of China. The architectural style took inspiration from what was common during that era, but in the context of the what we’re more familiar with here in Taiwan, it’s easy to see that it has taken on many of the architectural elements indicative of traditional Hokkien design.

In terms of its layout, the temple follows the rules of Feng Shui in that it ‘sits east and faces west’ (坐東朝西) towards the coast, which is especially important for a Mazu temple as she should be looking toward the coast. Differing slightly from a traditional temple design layout, the temple features four halls (四進建築), and its width is measured in ‘bays’ being three bays wide (面寬三開間), each of which is about 3.6 meters.

As mentioned above, the main part of the temple features four halls (殿) and an open courtyard (院) including the Front Entrance (三川殿), the Worship hall (拜殿), the Main Hall (正殿), and the Rear Hall (後殿).

What this description doesn’t account for however is that the wing on the left is home to an additional two halls: the Three Treasure Hall (三寶殿) and the Guanyin Hall (觀音殿), as well as a Rear Hall that was later extended and divided into two sections. In terms of the original design of the palace, the left side was used primarily as the residential part of the building and was converted into shrine rooms when the the palace was turned into a temple.

Despite being an important part of the temple today, the left side is rarely mentioned in official texts as the focus is always on the main part of the building as it is ‘newer’ but also not new at the same time. In traditional design terms however, the left side is a bit awkward as it takes away from the typical rectangular shape that most temples have.

The roof of the building is complex in that it is separated in a few different sections, the first part of the roof covers the Front Entrance and the Worship Hall while the larger roof covers the Main Hall and parts of the Rear Hall. The roof however is where the temple differentiates itself from almost all of its contemporaries across the country in that it is a gabled roof (硬山頂) with a round or curved sloping ridge (捲棚式屋架), the largest of its kind in Taiwan. Amazingly, it was constructed without the use of a single nail, held in place by a jigsaw-like network of trusses.

In term of the roof’s decorative elements, the curved part that covers most of the building is quite subdued in comparison to most of Taiwan’s other temples. However, the section that covers the front part of the Main Hall is dual-layered with the top section featuring a four-sided curved swallow-tail design (燕尾脊) and cut-porcelain carvings (剪瓷雕) along the ridges.

The section of roof that covers the front of the building is the most decorative portion in that it features a dual-layered swallow-tail design (雙脊燕尾造型), and is decorated with green porcelain dragons on each of its rising ridges. On the apex of the roof you’ll find the famed ‘Sanxing’ (三星) deities Fu, Lu and Shou (福祿壽) who are considered to the be embodiment of ‘Fortune’ (福), Prosperity (祿), and Longevity (壽), and are commonly found on temple roofs all across Taiwan. You’ll also find other cut-porcelain carvings (剪瓷雕) along the roof, which have become indicative of traditional Hokkien-style architecture in Taiwan.

Links: Sanxing | 三星 | Hokkien Architecture | 燕尾脊 (Wiki)

Now that we have the basics of the building’s architectural design out of the way, I’d like to spend some time discussing some of the building’s more decorative elements, which work hand-in-hand with its architecture. Like many of Tainan’s other temples, the devil often lies in the details with these things as you’re likely to pass by an object that is quite significant, without ever realizing it.

Main Gate (山川們)

Starting with the entrance to the temple, you’ll find something different from every other Mazu temple in the country. Instead of the typical Door Gods (門神) that you’ll find painted on the doors, this one is instead adorned with seventy-three door studs (廟門73門釘). Giant red doors with studs like these are typically reserved for palaces or official temples, and here in Taiwan you’ll generally only ever see them on Confucius Temples (孔廟) or Martyrs Shrines (忠烈祠). The door studs in the case of this temple can be viewed through a historic lens as the building was originally a palace for a prince, but also the first officially recognized Mazu temple in Taiwan. The studs essentially elevate the status of the temple and recognize it, and its goddess of the highest nobility.

The interesting thing about the door studs here is that there are (currently) an odd number of them, which is strange given that calculation of the number of studs is usually done by a factor of nine. The reason there is an extra one is because Emperor Kangxi ‘gifted’ the temple an extra stud, increasing the temple’s level of importance.

Standing on either side of the middle door you’ll find two stone guardian lions (石獅), both of which date back to the Qing dynasty. If you weren’t aware, the guardian lions always appear with one male and the other a female. The male lion at this temple has a ferocious appearance with his body erect while its forelegs are playing with a hydrangea. The female lion on the left on the other hand has a similar appearance, but instead has a baby lion between its forelegs.

Just behind the stone lions you’ll find two exquisitely carved Dragon Pilars (龍柱) with stone mined from Guanyin Mountain (觀音山) in Taipei. The pillars, which feature dragons encircling them are somewhat of a new addition to the temple (carved in 1959) replacing the originals which likely met their fate due to an earthquake.

The left and right walls in addition to the gate are likewise home to a number of historic stone-carved murals, each of which date back to the Qing Dynasty. The murals feature depictions of auspicious and mystical Chinese creatures, including peony birds, qilin (麒麟), phoenixes (龍鳳), dragons, lions, tigers, bats, etc.

Notably, above the stone murals on the left and right walls you’ll find golden Chinese characters that read ‘Dragon Growl’ (龍吟) and ‘Tiger Roar’ (虎嘯), a traditional phrase that goes together to mean ‘Good Fortune’ but in this case holds somewhat of a double meaning with the ‘dragon growl’ located next to the ‘Dragon Door’ (龍門) and the ‘Tiger Roar’ next to the Tiger Door (虎門).

Note: In Chinese, they say “龍門進虎門出“ (lóng mén jìn hǔ mén chū) which means that you should enter a temple through the “Dragon Door” (龍門) and exit via the “Tiger Door” (虎門). The reason for this is because entering the dragon symbolizes ”praying for happiness” while exiting through the tiger is thought to “ward off bad luck or misfortune”.

It is essentially a symbolic way of purifying yourself before you enter a temple. If you however were unaware of the rules and you entered through the tiger door, it would be considered to be bringing misfortune both for yourself and the temple, and thats not a good thing.

Likewise, the middle door (中門) is a space reserved for the gods or high-ranking government officials. If you’re wandering around a temple and you walk through the middle door, it could be considered bad luck because you’re blocking the view of the gods.

So, if you want to enter a temple, you should enter through the ‘Dragon Door’, which is on the far right. If you want to leave the temple, you should exit via the ‘Tiger Door’ on the left and if you want to make the gods angry, just walk through the middle door and try your luck.

Courtyard (螭廳)

The open-air courtyard in between the Worship Hall and the Main Hall doesn’t really feature all that much in terms of decoration, but the little that is there makes this area one of my favorite sections of the temple.

The walls on both the right and left sides feature round paintings set between two stone pillars with Chinese calligraphy on either side of the pillars. The Chinese calligraphy is an imitation of Confucian scholar Zhu Xi’s (朱熹) style with the words ‘Loyalty’ (忠) and 'Filial Piety’ (孝) on the right side and ‘Righteousness (義) and ‘Integrity’ (節) on the left. The calligraphy is really beautiful and if you look at each side from a distance you can really appreciate how beautiful they are.

On the right side, you’ll find a shelf of traditional weapons used by Mazu’s ‘Honor Guard’ (儀仗) and her ‘Silk Guard’ (絲仗). These weapons apparently only appear during the weekdays, and they’re only there for decorative purposes, but they’re actually something that you’ll come across often in some of Tainan’s other historic temples, less so in other areas of the country.

As you climb the stairs to approach the Main Hall you’ll find four stone heads protruding from the stone base, something that is extremely uncommon among Taiwan’s temples. A Chinese-style gargoyle if you will, the heads are referred to as “Chi” (螭首), a hornless dragon. These miniature dragons are common decorations in imperial palaces back in China, but here in Taiwan are quite rare.

The heads date back to 1664 (明永曆18年), and served not only a decorative purpose but a functional one as well as the open mouths of the dragons served as drains for rainwater that accumulated in the Main Hall.

Unfortunately, even though it would be pretty cool to see water pouring out of their mouths, the drainage function doesn’t exist anymore. As a leftover from the palace that existed in the building before the temple, this is one of the only temples in the country to feature them.

Before I finish, I want to touch on some important decorative elements that you’ll find throughout the temple, each of which have historic or cultural significance. The temple is full of paintings, plaques and stone steles, which are pretty important but rarely ever get much attention in English.

Ancient Inscription Plaques (古匾額)

Tainan is a pretty historic city, but if anything its a pretty significant place when it comes to ancient plaques.

You might be thinking, “plaques? What’s so special about them?”

There are more of these plaques, which were gifts from Qing Emperors, in the city than anywhere else in Taiwan. Almost every major temple in the city has at least one, but none of them have as many as the Grand Temple - where there are more than a hundred. Obviously, I’m not going to list each of them below, but it’s important to draw attention to the five most important.

Each of the plaques will be listed below, with a rough translation, the year they were gifted to the temple, and by which emperor. These ancient Chinese idioms aren’t particularly the easiest to translate into English, so please bear with me on this one, I’ll try to get them as close as possible.

“Divine Protection from on land and sea”「輝煌海澨」 - 1684 (康熙23年) Gifted by Kangxi Emperor

“The Divine Power of the Sea”「神昭海表」 - 1726 (雍正4年) Gifted by Yongzheng Emperor

“The Power to Fulfill your Wishes”「佑濟昭靈」 - 1788 (乾隆53年) Gifted by Qianlong Emperor

“Kindness and Virtue that Transcend the Ages”「德侔厚載」 - 1853 (咸豐3年) Gifted by Xianfeng Emperor

“Working hand in hand with heaven”「與天同功」 - 1881 (光緒7年) Gifted by Guanxu Emperor

Paintings (名家彩繪)

The paintings you’ll currently find on the walls of the temple aren’t exactly ‘historic’ given that most of them have been painted within the past century - but they were all painted by some pretty legendary artists, known in Taiwan for some very iconic work, especially when with regard to traditional temple art around the country.

1943 (昭和18年) - Chen Yufeng (陳玉峰) - located on left and right sides of the Main Hall and in the Sacred Parents Shrine.

1956 (民國45年) - Chen Yufeng (陳玉峰) - twelve images located on the walls in the Worship Hall

1971 (民國60年) - Pan Lishui (潘麗水) - painting of Mulan (花木蘭) in the Sacred Parents Hall and murals on the wall within the Three Treasure Hall.

1976 (民國67年) - Chen Shouyi (陳壽彝) - The son of Chen Yufeng repainted the original works of his father in the Worship Hall and the Main Hall after they had faded

1980 (民國69年) - Ding Qingshi (丁清石) - Recolored the work of Chen Yufeng’s 1956 works in the Worship Hall.

1997 (民國86年) - Pan Xuexiong (潘岳雄) - The son of Pan Lishui, repainted some of the pieces created by his father.

Stone Steles (石碑記)

These days, when temples want to mark an occasion or draw people’s attention to something, they install a bunch of flashing lights and a gaudy LED signboard that gets their message across. During the Qing dynasty however, it was more common to have a giant stone tablet inscribed with hard to read calligraphy and art to mark an occasion. Somewhat of a lost art form in Taiwan these days, the Grand Mazu Temple is home to several of the nation’s oldest and most prized steles. Like the paintings mentioned above, these tablets are a work of art in their own right, and even though they might just look like giant stone tablets with fading words on them to the naked eye, you should take a look when you visit the temple.

1685 (康熙24年) - ‘Stele of the Pacification of Taiwan’ (平台紀略碑記) - erected by Admiral Shi Lang, its the oldest stele in Taiwan and recollects the events that led up to the surrender of the short-lived Kingdom of Tungning. It is currently located on the left wall of the Worship Hall is somewhat of a national treasure.

1693 (康熙32年) - ‘Stele of Merit and Appreciation for Admiral Shi Lang’ (靖海將軍侯施公功德碑記) - The second oldest stele tablet in Taiwan, this one was erected in the temple in appreciation for the donations made by Admiral Shi Lang to Tainan’s places of worship. It’s currently located against the right wall of the Worship Hall.

1778 (乾隆43年) - ‘Record of Restoration Stele’ (重修天后宮碑記) - Essentially a record of the three year process of restoration of the temple that converted it into the layout that we know today. The stele is located along the left wall of the Worship Hall.

1830 (道光10年) ‘Record of Restoration Stele’ (重興大天后宮碑記) - A second stele that records the efforts to restore the temple. The stele is located along the right wall of the Worship hall.

Getting There

Address: #18, Lane #227, Yongfu Road Section 2, Tainan City

GPS: 22.996530, 120.201560

Hours: Open daily from 5:30am - 9:00pm

Located within Tainan’s historic West-Central District’s (中西區) Chihkan Cultural Zone (赤崁文化園區), which is home to the famed Chihkan Tower (赤崁樓), the God of War Temple (武廟) and a ton of amazing restaurants that focus on local cuisine. The Mazu temple is a short walk from each and is also within walking distance from some of the city’s other important tourist attractions, including the Tainan Confucius Temple (台南孔廟), Tainan Martial Arts Hall (台南武德殿), the Taiwan Prefectural City God Temple (臺灣府城隍廟), Shennong Street (神農街), as well as the train station.

If you weren’t already aware, Tainan is a very walkable city and every street and alley you pass by features an incredible amount of local history. You could easily drive a car or a scooter around town, but you’d really be missing out on a lot of the city’s charms. My best recommendation for getting around, if you’ve got your own means of transportation is to simply find a parking spot and from there enjoy the city on foot. That being said, Tainan is as modern as it is historic, so there are a number of public transport options for getting around the city and getting to this historic temple.

High Speed Rail / Train

If you’ve arrived in the city by way of the High Speed Rail you have a couple of options for getting to the area. First, you can take the free HSR Shuttle Bus to Tainan Train Station (台南火車站) and from there making use of any of the public transportation options listed below. Or you could take a more direct route by taking Tainan City Bus (台南公車) #3, #5, #88 or #99 and getting off at the Chihkan Tower stop.

Similarly, if you’ve arrived in town by train, you are within walking distance from the temple, or you could make use of any o the public transportation options listed below.

Walking

The best point of reference for getting to the Mazu temple is from Chihkan Tower, which can be found pretty easily thanks to the various methods of public transportation. From the tower, walking to the temple is quite simple as you just have to cross Minzu Road (民族路二段) where you’ll have the option of either walking past the God of War temple and through the stone alley that leads you to the temple or walking a little further east from down Minzu Road where you’ll find the newly constructed main gate to the temple.

Public Bus

There are three bus stops within three hundred meters of the temple, so you have quite a few options for taking a bus from wherever you are. Admittedly, there are far too many buses that service each of these three stops, so instead of linking to each of them below, I’m just going to provide a Google Maps link to each of the stops which will provide the list of routes and allow you to figure out which one is best for you.

Chihkan Tower Bus Stop (赤崁樓站) - 80 meters from the temple

West Gate Traffic Circle Stop (西門圓環站) - 180 meters from the temple

Ximen Road Section 2 Stop (西門路二段站) - 280 meters from the temple

Shared Bicycles

Unlike many of Taiwan’s other cities, Tainan has yet to succumb to the popular Youbike shared bicycle rental service. The city is sticking to its own ‘Tbike’ (臺南市公共自行車) service, and travelers can easily access the system with their EasyCard, iPass, iCash or credit card. But you’ll have to register your card at one of the kiosks around the city before taking off.

Link: T-Bike Rental Information (Tbike)

There are three docking stations located within a short walking distance of the temple and the Chihkan Cultural Zone where you’ll be able to pick up or return one of the bikes. As is the case with each of the bus stops above, I’ll provide a link to the location of each of the docking stations in the area on Google Maps below. If you’ve just arrived in Tainan on the train, you can easily grab one of the bikes in front of the station and make your way over to the Chihkan Cultural Zone area, which will probably take you less than five minutes.

Chihkan Tower T-bike Dock (赤崁樓站)

Haian-Minzu T-Bike Dock (海安民族站)

Family Education Center T-Bike Dock (家庭教育中心站)

Car

Finally, if you’re driving a car, there are three parking lots nearby where you’ll be able to park your car and make your way to the temple. Mind you, parking within this part of town is going to be a little more expensive than other parts of the city given that the area is a popular tourist destination. If you’re driving, you might also want to try to find street side parking on one of the side streets adjacent to Minzu Road.

The parking lots closest to the Chihkan Cultural Zone are as follows:

Minchuan Road Parking Lot (民權路二段收費停車場)

Fucheng Parking Lot (府城停車場)

Zhongcheng Road Parking Lot (中成路停車場)

Huan-an Parking Lot (環安停車場)

Whatever method you take the get to the temple, I highly recommend you visit Chihkan Tower and the God of War Temple which you’re there. While in the area, I also recommend you try some of the restaurants that line both sides of Minzu road that show case some amazing local cuisine. Or you could try the simple, yet really tasty Yamane Sushi (山根壽司) while sipping a refreshing drink from the famed Winter-melon Tea shop (義豐阿川冬瓜茶) across the street from the God of War temple. You could easily spend the better part of the day within this city block enjoying the historic sites and eating and drinking your way through the city.

And if you stay there in the area long enough, I highly recommend checking out Bar TCRC (前科累累俱樂部), one of the country’s most well-loved cocktail bars.

You might need to make a reservation though, the place is pretty popular!

Like a trip to Taipei’s Longshan Temple (艋舺龍山寺), a visit to the Grand Mazu Temple isn’t just an experience that should be shared by the religious - this temple is one of the most historic places of worship in the country and when you visit you’ll get a crash course in Taiwan’s history while walking around, especially if you include a stop at the Chihkan Tower and the God of War temple as well. The temple is more or less one of the must-visit destinations on any trip to Tainan, and as one of my personal favorite temples in Taiwan, I cannot recommend enough that you pay this one a visit while you’re in Tainan.

References

Grand Mazu Temple | 大天后宮 (Wiki)

Grand Mazu Temple | 大天后宮 (Taiwan Tourism Bureau)

Tainan Grand Matsu Temple | 臺南祀典大天后宮 (臺灣宗教百景)

Tainan Grand Matsu Temple (Tainan City Guide)

臺南祀典大天后宮 (Official Page)

全臺祀典大天后宮「明寧靖王府邸」 (台南旅遊網)

祀典臺南大天后宮志 (曾吉連)

祀典台南大天后宮(二) 鎮殿媽祖 (逸想天開)

祀典「台南大天后宮」的過去與現在 (台南市九十三年度國中小師生鄉土主題探 究比賽)

臺南大天后宮的歷史與場域之研究 (毛紹周)

台南大天后宮傳統設計之研究 (郭旭姬)