Given that you can find a City God temple in every major city, town or village in Taiwan, it shouldn’t surprise anyone to know that there are close to a hundred of these places of worship throughout the country, celebrating an ancient Chinese folk religious tradition.

Having already published articles about the Xiahai City God Temple (霞海城隍廟), one of Taipei’s most important places of worship, and Hsinchu’s City God Temple (新竹城隍廟), the headquarters of all City God Temples in Taiwan, I figured it was about time to do another deep dive about one of the nation’s other ‘most influential’ City God temples - the one that started it all, namely the Taiwan Prefectural City God Temple (臺灣府城隍廟) in Tainan.

With a history spanning several centuries, the temple originated during the Kingdom of Tungning era, and has continued to thrive through the Qing era, the Japanese era, and the current Republic of China era.

To put it simply, this City God temple has lived through some of the most tumultuous periods of Taiwan’s modern history, and continues to stand today as one of the nation’s most important places of worship, a national treasure if you will.

That being said, when you see someone claim that it’s three and a half centuries old, it’s true, but not necessarily true at the same time.

Link: List of City God Temples in Taiwan 臺灣城隍廟列表 (Wiki)

Surprisingly, there are few articles that go into much detail about this important place of worship, both in Chinese or English, so I’ll be doing a bit of a deep dive on this one having spent a considerable amount of time researching its history and architectural design. So with that in mind, I’m just going to get right into it.

Taiwan Prefectural City God Temple (臺灣府城隍廟)

Few places of worship (or any building for that matter) in Taiwan can claim a history of over three and a half centuries, but if you’re looking for some, look no further than the southern city of Tainan

Tainan as an organized city has changed considerably over the various periods of Taiwan’s modern development, but starting from the Dutch era, the city became an important trading port for the European powers. Things changed considerably however when Koxinga (鄭成功) and his band of pirate ships showed up and forcibly removed the Dutch. The large fleet of ships (fleeing dynastic regime change back in China) arrived in Taiwan hoping to ‘regroup’ in order to go back to China and restore the Ming Emperor.

Koxinga, and his family quickly established a Chinese-style settlement in Tainan, which (at that time) was referred to as ’Hú-siâ’ (府城) in Hokkien, which is where the temple derives its name.

While developing the city, which would ultimately become the capital of the Kingdom of Tunging (東寧王國), it was important for the ruling class that a ‘Chinese style societal structure’ was imposed on the people of the newly formed kingdom. So, they founded a Confucius Temple, the first in Taiwan - which was tasked with training civil servants. It is said that Koxinga placed quite a bit of importance on Confucian thought and philosophy, and the construction of a shrine, where Imperial Examinations (科舉) could be held was important to the fledgling ‘kingdom’ seeking to maintain the traditions of the Ming dynasty.

With the Confucius Temple constructed in 1665, one of the next steps for the Zheng Family was to construct a City God Temple for which they could better instill the values of the newly formed system of governance. One of the things that you have to keep in mind about City God worship (I’ll explain more later) is that the City God is essentially a celestial civil servant, like a governor or a mayor - and it is the role of his court to oversee everything that is taking place within his territorial boundaries. The human rulers of a specific area were required to pay homage to the local City God, while at the same time using his example to teach people about traditional Chinese styles of governance. That being said, life in the early days of an undeveloped Tainan was harsh, and even Koxinga himself died of Malaria, so even though City God worship was beneficial to the ruling elite, it might have also been to their detriment if they weren’t living in a military dictatorship.

Constructed in 1669 as the “Sêng-thian-hú Prefectural City God Temple” (承天府城隍廟), the temple, like its Confucius Temple counterpart, was the first of its kind in Taiwan, and the City God enshrined within was considered to be the highest ranking in the ‘prefecture’, which pretty much meant the entire island of Taiwan.

Language note: The words “Sêng-thian-hú” are the Taiwanese Hokkien pronunciation for “Cheng-tian fu” (承天府), which was the term used at the time to refer to the governing territory of Taiwan. Similarly, Chinese capitals Nanjing (南京) and Beijing (北京) were referred to as “Ying-tian fu” (應天府) and “Shun-tian fu” (順天府) respectively.

When the temple was constructed over three and a half centuries ago, it was a considerably smaller place of worship than it appears today - As you’ll see in the timeline provided below, there have been numerous occasions where the temple was renovated, expanded upon and restored, culminating in it doubling in size with additional shrines and decorations added later.

With regard to architectural changes though, I’ll touch more on that later.

What I think is important to note about the City God temple was the special relationship it maintained with regard to the ever-changing political situation over the various eras of Taiwan’s modern history. The temple was regarded as the most important City God temple during the Kingdom of Tungning era, which lasted from 1661–1683. When the Qing took control of Taiwan, it maintained its role as the highest-ranking shrine in Taiwan until 1891 when the Qing court officially recognized the Hsinchu City God Temple as the highest-ranking temple in Taiwan. Not much changed in this regard during the Japanese-era, but when the Chinese Nationalists took control of Taiwan, they constructed the “Taiwan Provincial City God Temple” (臺灣省城隍廟) in Taipei and attempted to shift the balance of power away from the Hsinchu temple, but it doesn’t really seem like many actually paid attention to those efforts.

These days we have a bit of a delicate situation with three high-ranking City God’s presiding over the nation - but when it comes to people’s attitudes about these temples, the Hsinchu Temple is probably the most popular as it maintains its role as the ‘headquarters’ of all of Taiwan’s nearly one-hundred City God temples. The Tainan temple on the other hand is highly respected as it is the first of its kind in Taiwan, and its history and architectural design are considered to be a national treasure, which is why it has been permitted to keep its name.

And the temple in Taipei… Well, I suppose it was useful for propaganda purposes, but it’s neither historic, nor as widely frequented as the other two.

Below, I’ve created a timeline of some of the most important events in the temple’s long history:

Timeline

1661 (永曆15年) - The Kingdom of Tungning (東寧王國) is established in Tainan by Koxinga and his army of Ming loyalists.

1665 (康熙4年) - The Tainan Confucius Temple is officially established nearby in an effort to promote Ming Dynasty-style governance and cultivating a local civil service.

1669 (永曆23年) - The “Chengtian Prefectural City God Temple” (承天府城隍廟) is constructed in an eastern area of the city then known as ‘Tong-an-hong’ (東安坊) near the East Gate (東門).

1683 (康熙22年) - The Kingdom of Tungning is annexed by the Qing, who take control of parts of Taiwan.

1693 (康熙32年) - The temple undergoes its first of many renovation and restoration projects.

1752 (乾隆17年) - Official records indicate that the renovation project started decades earlier is completed and the the temple design is officially a ‘Two Hall’ (兩段式廟宇) layout.

1758 (乾隆24年) - 1777 (乾隆42年) - Once again, the temple is renovated and expanded on and pretty much doubles in size transforming into the layout that we see today (四進兩廂房式的廟宇建築).

1827 (道光7年) - The temple undergoes a period of repair (natural disaster related)

1828 (道光8年) - The temple is officially renamed “Taiwan Prefectural City God Temple” (臺灣府城隍廟).

1862 (同治元年) - The temple undergoes a period of repair (natural disaster related)

1890 (光緒16年) - The temple undergoes a period of repair (natural disaster related)

1891 (光緒17年) - Hsinchu is upgraded as a city in Taipei Prefecture, and the Hsinchu City God temple is upgraded into a prefectural-level temple.

1895 (明知28年) - Japan takes control of Taiwan.

1907 (明知40年) - Due to Japan’s urban renewal plans, the road in front of the temple is modernized and widened for cars, reducing the size of the front court yard.

1934 (昭和9年) - The temple undergoes another period of extensive restoration and modernization with celebrations held at the end of the project.

1937 (昭和12年) - The '爾來了’ plaque is gifted to the temple.

1945 (民國34年) - Japan surrenders control of Taiwan and the temple starts a long restoration project.

1947 (民國36年) - The Taiwan Provincial City God Temple (臺灣省城隍廟) is constructed in Taipei and the City God once again is ranked the highest in Taiwan, another awkward situation.

1952 (民國41年) - After seven years, the restoration project is finally completed.

1975 (民國64年) - The temple undergoes another period of restoration and new Door Gods are added by a famed local artist named Pan Lishui.

1982 (民國71年) - Qingnian Road is widened to 15m, reducing the size of the front courtyard (廟埕) and putting the road next to the front door.

1983 (民國85年) - The temple undergoes a period of restoration paid for by the government.

2005 (民國94年) - The temple is officially designated as a protected historic site (國定古蹟).

Now that we’ve talked a bit about the history of this temple, to better understand the deities enshrined within, I’ll introduce them individually as briefly as I can. Before I do, keep in mind that even though this temple is primarily a Chinese Folk Religion place of worship, you’re also going to find figures commonly associated with Taoism and Buddhism. The great thing about this is that unlike other areas around the world, here in Taiwan the mixing of religious traditions isn’t a big deal, and everyone has happily gotten along for the past few hundred years.

The City God (城隍爺)

Most often referred to as the City God (城隍) in English, "Cheng Huang Ye" (城隍爺) is an influential figure in Taoism, and even though he’s considered a ‘tutelary’ deity (and isn’t one of the figures that frequents the Jade Emperor’s celestial court), he is still an important figure within the hierarchy of deities, especially within Chinese Folk Religion.

Worship of the City God is thought to have originated over two thousand years ago, but is a religious tradition that has evolved over time with changes in political ideology, in addition to societal changes, and the concept of a modern city or town. Once a minor figure within Chinese Folk Religion, worship of the City God was popularized during the late stages of the Ming Dynasty, and continued well into the Qing Dynasty.

Considered to be a protector deity, the City God acts as a liaison between the living and the supernatural and plays an important role in assisting the earthly bureaucracy in making the ‘right’ decisions in addition to assisting governments in maintaining order. The function of the City God, whose name literally translates as the god of "walls and moats" (城 means 'city' while 隍 is a 'moat') was to act as a supernatural 'magistrate' who would make decisions about a city's governance (along with human colleagues). He was also responsible for acting as a judge for those citizens who lived within the borders of the city, in addition to working to keep it safe.

Essentially, the City God is not unlike a traditional court official governing from a throne room with a long list of assistants helping to maintain order. As a supernatural magistrate, City God shrines typically appear in a similar design to what you’d expect from a throne room, and the City God is always surrounded by his officials and protectors. From his throne room, the City God would help to oversee development of the city and its defense, and assist in solving issues for the citizens living within his jurisdiction and more importantly handing out judgement for those who have done wrong.

The traditional role of the City God has evolved over time and these days fills the role of an ‘all-purpose’ deity who holds authority with regard to matters of life and death within his specific territory, but also offers assistance to people suffering from poor health, or other contemporary issues. With the societal shifts mentioned above, the City God has changed with the times and has transformed from a simple village guardian to a figure regarded as a protector deity of the modern-nation-state.

One area that sets the City God apart from many of his supernatural colleagues is that in the early days of City God worship, if people prayed for rain and the god failed to 'bring the rain', it was within their ability to hold the god 'accountable' and punish him. Punishments for such heinous inaction on the part of the City God could include leaving his statue out in the hot sun, or having the local governor or magistrate whip him.

This is something that is pretty much unfathomable for the high-ranking members of the Jade Emperor’s Celestial Court, but is an interesting concept where even supernatural beings are able to be held accountable for not holding up their end of the bargain!

These days, worship of the City God has changed considerably, and the notion of dragging him out of his throne room to torture him is probably impossible. Even here in Taiwan where there are ninety-five temples dedicated in his honor, no one mistreated any of his statues during the most recent several-year long drought which caused water shortages around the country.

One thing that most people don’t actually realize about the City God is that his supernatural powers are divided up based on the area that he represents, which is something that is quite significant to this temple; To put it simply, if you come across a City God temple in a small town or city, his influence isn’t as powerful as that of a ‘prefectural’ or ‘national-level’ version.

The City God’s official divisions are as follows:

National Level City God (都城隍、府城隍), known formally as the Duke Xiang (享公爵)

State / Provincial Level City God (州城隍), known formally as the Marquis of Xiang (享侯爵)

County / Town Level City God (縣城隍), known formally as the Earl of Xiang (享伯爵)

Given that this is the ‘Taiwan Prefectural City God Temple’, the City God that is enshrined within is the National Level City God, who is regarded as the “Duke of Wei” (衛靈公) and is one of the highest ranking in Taiwan.

Having already read the history of the temple above, you’ll know that when it was first constructed, during the short-lived Kingdom of Tungning era, where its purpose was to serve in the capital of the kingdom, which was located in present-day Tainan. With that in mind, it’s important to note that there is also a ‘Duke of Wei’ level City God in the Hsinchu City God Temple, which is currently the most influential City God temple in Taiwan as it acts as the headquarters for the rest.

Ultimately when it comes to the City God, there is a considerable amount of politics that needs to be taken into consideration, and that is usually something that takes place here with us humans who use these images to our own advantage.

The Civil and Martial Judges (文武判官)

Accompanying the City God in the main shrine of the temple you’ll find standing statues of two of the City God’s most important officials, the Civil and Martial Judges. Starting on the right, you’ll find the “Civil Judge” (文判官) with the ‘book of life and death’ (生死簿) in one hand and a brush in the other. The function of the Civil Judge is to record both the good and bad deeds in ones life and judge them accordingly when they pass away. On the left, you’ll find the “Martial Judge” (武判官), who is responsible for the enforcement of the City God’s judgements. Holding a mace in his left hand, this judge is a much more opposing and serious-looking figure and is responsible for the scarier aspects of a City God’s duties.

The City God’s Twenty-Four Officials (二十四司 / 司爺)

Located within a glass-covered compartment on walls to the left and right of the main shrine you’ll find twenty-four statues of the rest of the City God’s spiritual assistants. According to tradition, the twenty-four officials are an imitation of the ancient official system of governance in China with each of the officials performing a specific duty. In a contemporary sense, they are basically ‘department heads’ or ministers of each of their respective bureaus. For brevity, I won’t be going into detail about each of their names or their responsibilities, but for example you’ll find someone who takes care of labor rights, household rights, education, national defense, etc.

For reference: Their names are as follows: 陰陽司、速報司、稽查司、賞善司、罰惡司、註福司、註壽司、功曹司、良願司、提刑司、地獄司、驅疫司、感應司、文書司、檢簿司、掌案司、考功司、保安司、查過司、學政司、典籍司、督糧司、巡政司、儀禮司。

Unfortunately there isn’t very much information available about these guys in English, so if I find some time in the future, I might go into a bit more detail about them with a dedicated article. They’re actually quite interesting and are essentially a supernatural mirror into the way people perceived governance a thousand or more years ago.

Generals Fan and Hsieh (范謝將軍)

Located at the entrance to the temple, you’ll find shrines dedicated to General Fan (范將軍) and General Hsieh (謝將軍), who together are more commonly known as the “Seventh and Eighth Lords” (七爺八爺), or the “Black and White Impermanence” (黑白無常), and are common figures within Taiwan’s religious scene, especially at temple festivals.

Often appearing in parades with long waving hands, the two generals are important members of the City Gods court and are charged with carrying out the task of escorting the dead to trial to be judged by the City God.

Link: 范謝將軍 (Wiki)

How does one go about telling the two generals apart?

Well, their name “Black and White Impermanence” as mentioned above is probably one of the best indications given that one of the generals appears in white while the other is black. General Hsieh, who greets you at the entrance to the temple (right side) is tall and thin, and wears while robes with long eyebrows and a beard. His counterpart, General Fan, on the other hand is short and chubby with dark skin and a black robe.

Given that the two of these generals play an important role in carrying out the judgements of the City God, (especially with regard to the afterlife), having them at the front door is a constant reminder to anyone who enters that they should be on their best behavior.

General Hsieh: Wearing white robes and holding a feather fan in his hand.

General Fan: Wearing black robes and holding a square card connected to a chain that has tiger heads painted on it.

Generals Gan and Liu (甘柳將軍)

Accompanying the smaller statues of General Fan and Hsieh are two of their associates, General’s Gan (甘爺) and Liu (柳爺), who are famously part of the fierce Eight Generals (八家將), and can be commonly found roaming the streets (in human form) during temple festivals.

Both generals are part of the “Front Line” (頭排) of the group of underworld immortals and are responsible for carrying out executions.

Interestingly, they take turns supervising people’s good and bad deeds during the day, which means that you won’t often find them appearing together unless there is an important event.

In statue form, they appear quite menacing, but when they’re in human form in front of you on the street with their weapons used for torture, they’re even scarier. Still, they’re part of one of the coolest aspects of Taiwan temple culture, and their appearance at any event is an important occasion.

The City God's Wife (城隍夫人)

In the rear hall, you’ll find a second City God-related shrine dedicated to his wife, who is known simply as “The City God’s Wife.”

Despite the obvious arguments of gender inequality that come with this, the City God's Wife is an important fixture within any City God temple, and a temple dedicated to the City God couldn’t be complete without a shrine to his wife, who also performs official state functions like her husband.

While the City God is busy being the all-important political figure, his wife deals with matters of the heart and is known as a ‘Chinese Cupid’ of sorts. Tradition has it that if you’re praying for love, marriage or having children, she’s the one you’ll want to visit in order to take care of all your needs.

Making things even better, if your husband has undesirable habits such as gambling, drinking or sleeping around - she'll also help take care of that!

While it may come across as a sexist tradition to some, the City God's wife is highly respected, and with a palace of her own, she’s just as important as the City God himself. And as mentioned above, taking into consideration that these temples are often a reflection of the ancient Chinese court-system, their shrines mirror that of the roles that leaders of the past would have had.

Interestingly, in many City God temples you’ll often find photos of happy couples posted nearby the shrine to the City God’s wife thanking her for her assistance in helping people to find true love.

In the case of this temple, the City God’s Wife is located in the Rear Shrine (後殿), but she isn’t located in the main shrine in the centre as you’ll find in other City God temples. Her shrine is to the right of the main shrine, and in another departure from what you’d typically see in one of her shrines, she is accompanied by a statue of her husband, who sits side-by-side with her.

The Goddess of Child Birth (註生娘娘)

Following along with shrines that are predominately dedicated to women, visitors will find a statue dedicated to the ‘Goddess of Childbirth’, also known as the ‘Goddess of Fertility’ (註生娘娘), who is of the most highly respected fertility deities in Chinese Folk Religion, especially for those hailing from the Southern Fujian region of China - where many of the first immigrants to Taiwan originated.

Holding a notebook in one hand and a brush in the other, she is in charge of recording the births of every household, and does her best to assist anyone having trouble having children.

Ms. Linshui (臨水夫人)

Sitting next to the Goddess of Child Birth, you’ll find another Southern Fujianese goddess, “Ms. Linshui” (臨水夫人). With regard to the English translation of her name, I decided to go with “Ms.” instead of “Wife” as is the case with the City God’s partner above.

This is due to the fact that I’m not particularly sure who her husband is supposed to be and the word “夫人” doesn’t necessarily have to mean “wife” as it was a sign of respect (for women) hundreds of years ago.

According to legend, Ms. Linshui was a well-known Taoist priest named Chen Jinggu (陳靖姑) who became a goddess after death. Known to the Hokkien people as a protector of villages, she is also known as the patron saint of women and children.

Mazu (天上聖母)

Rounding out the shrine dedicated to Southern Fujian goddesses, I’ve saved the most important for last - Mazu (媽祖), or the Goddess of Heaven (天上聖母) is arguably the most important religious figure in Taiwan, and is regarded as the patron saint of the country.

Finding a shrine dedicated to the ‘heavenly mother’ is a pretty common thing in Taiwan, and even moreso in Tainan, but it’s important to remember that when this shrine was constructed, Mazu worship in Taiwan was still relatively new.

The statue of Mazu here certainly isn’t as grand as what you’d find at the nearby Goddess of Heaven Temple (天后宮), but given that she’s situated next to some other amazing Hokkien goddesses, its a pretty important one that represents the power and important role that women play in society.

Guanyin (觀音菩薩)

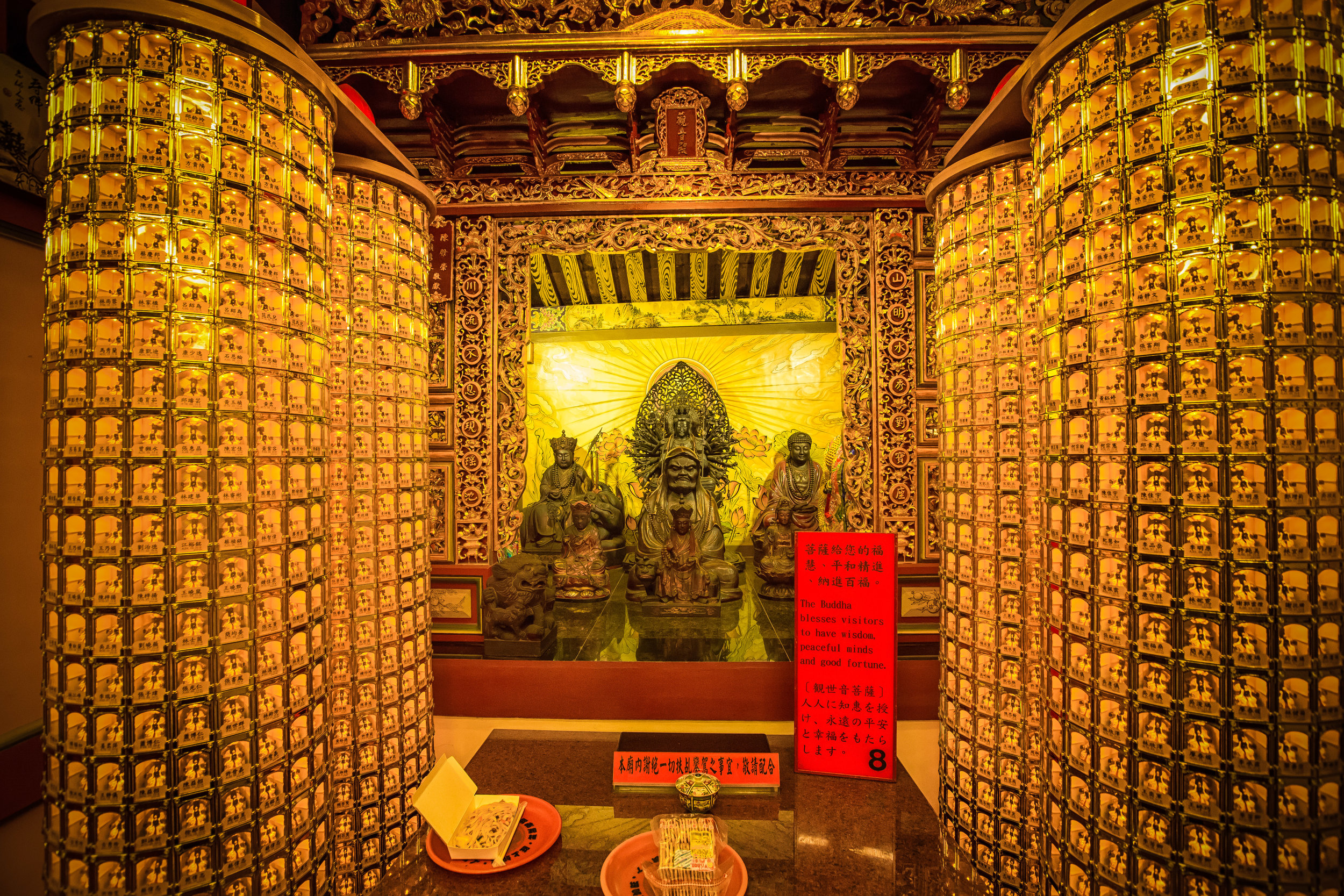

Located within the middle shrine in the rear hall is the Buddha of Compassion, known throughout the Mandarin speaking world as Guanyin (觀音菩薩).

Within the Mahayana Buddhist tradition, the Buddha of Compassion is a Buddha who is constantly reborn with the mission to ensure that all of humanity has the opportunity to reach enlightenment.

In Tibet, the Buddha of Compassion is none other than the Dalai Lama, but in Taiwan, China and other parts of Asia, the Buddha manifests as the mother-like Guanyin. Here in Taiwan, Guanyin is one of the most highly regarded Buddhist figures, and her worship transcends Buddhism, which is why you’ll often find shrines in her honor within Taoist and folk religion temples, like this one.

With that in mind, as the Buddha of Compassion, whenever something bad happens, Guanyin is always one of the first religious figures that people think of, so it shouldn’t be surprising that there is a shrine in her honor in this temple.

What does surprise me however is that her shrine is located in the middle position, which in most cases should be reserved for the throne of the City God’s Wife. Unfortunately I’ve been unable to find any explanation as to why it was set up in this way.

The Eighteen Arhats (十八羅漢)

Given that the main shrine in the rear palace is primarily dedicated to Guanyin, a Buddhist figure, you’ll find statues of the ‘eighteen disciples’ of the Buddha located along the left and right walls, with nine on each side. The eighteen arhats are interesting figures, so if you’re visiting the temple, I recommend taking a close look at each of the statues as some of them are likely to appear a bit differently than what you’d expect from one of the Buddha’s disciples.

Like the twenty-four judges above, I won’t be going into too much detail about the arhats as there is already an ample amount of information about them online. If you’d like to know more, click one of the links below.

Link: Eighteen Arhats | 十八羅漢 (Wiki)

Ksitigarbha (地藏菩薩)

Kṣitigarbha Buddha, known in Taiwan and China as “Dizang” (地藏菩薩), and Japan as “Jizo”(じぞうぼさつ), like Guanyin mentioned above is another Buddha who has vowed to continue being reborn until his mission is complete. In this case though, Ksitigarbha’s mission is to ensure that all of the people suffering through ‘karmic hell’ are eventually guided through to enlightenment. The role this Buddha plays in countries across Asia differs slightly, but taking into consideration how Taiwan has been influenced by both Chinese and Japanese Buddhist traditions, his worship tends to be a mixture of the two.

Link: Kṣitigarbha | 地藏菩薩 (Wiki)

In Japan, he plays a role similar to Taiwan’s Earth God (described below), and is also a protector of women and children, and pays special attention to unborn children. In the Chinese tradition, he is the person people visit to pray for blessings to the souls of their ancestors.

The Earth God (福德正神)

Located along the passageway to the right of the rear shrine you’ll find a shrine set up another one of Taiwan’s most important deities, the Earth God (福德正神).

If I was to make an analogy about deities in Taiwan, shrines dedicated to Mazu would be a bit like Family Mart (全家) while shrines dedicated to the Earth God are like 7-11 convenience stores. This is to say that there are certainly more 7-11’s around the country, but Family Mart is still pretty awesome.

Even though Mazu is regarded as the patron saint of Taiwan, the Earth God remains to be one of the most highly worshiped deities around the country, and temples and shrines in his honor can be found pretty much everywhere. Shrines to the Earth God are likely to be found in almost every major temple, so even though the shrine here isn’t at the forefront of the temple, his inclusion is still a necessity.

Accompanying the Earth God is one of my favorite folk religion figures, the Tiger General (虎爺將軍), who you’ll find located just below the shrine to the Earth God. Legend has it that the Tiger General is so ferocious that only the Earth God can contain him. While it may appear that the Tiger General is the Earth God’s pet, I wouldn’t say something like that out loud.

When it comes to evil spirits, the Tiger General is especially skilled at scaring them off. He’s also known as the protector of children, and is known for his skills when it comes to helping people make money.

The God of Matchmaking (月下老人)

Last but not least, the temple features a modest shrine to the ‘God of Matchmaking’, known literally as the “Old Man Under the Moon” (月下老人) or “Yue Lao” (月老). You might be thinking, “Hey doesn’t the City God’s Wife already cover that?”, and you’d be right. But within Chinese Folk Religious traditions, the God of Matchmaking is your go-to person for all romance-related problems, whereas the City God’s wife focuses much of her power on taking care of women.

The shrine to the God of Matchmaking is located along the western wall of the rear hall, and you’ll notice that there are lots of photos of couples next to the shrine. Sometimes the photos of these couples are fun to look at, because they’re all people who visited the shrine looking for love, and came back later to thank the god when they found someone.

Architectural Design

Even though the layout of the temple has changed considerably over the past three and a half centuries, it continues to maintain what you’d consider a traditional architectural design. Constructed in a North-facing-South (座北朝南) direction, the layout consists of ‘three hall and two-passage-way’ design (三殿兩護龍). What this means in layman's terms is that the temple was constructed according to Feng Shui, and is rectangular in shape with three different sections, a common design for temples.

With regard to the three ‘halls’ (殿), the front reception area (山門) acts as the one of the halls, while the City God shrine is located in the ‘Main Hall’ (正殿), and the ‘Rear Hall’ (後殿) is located behind that and features another shrine room. The two ‘passage ways’ on the other hand are located along the east and west-side walls, and in contemporary terms would be referred to simply as ‘walkways’ (走廊), but in a folk religion setting they are given the official name, ‘protector dragons’ (護龍), and allow visitors to make their way from the front entrance all the way to the rear courtyard in a counter-clockwise direction.

Starting from the front of the temple, you’ll find that the entrance has three doors, known locally as the Dragon Door (龍門), Middle Door (中門) and Tiger door (虎門). Located on either side of the Middle Door you’ll find a pair of beautifully carved Stone Lion Guardians (石獅), each of which date back to 1937 and amazingly continue to have their Japanese-era dates displayed on the base, which reads “Showa Era Year 12” (昭和丁丑).

The roof of the front hall is designed with a traditional single-layered swallow-tail design (單脊燕尾造型), and is decorated with green porcelain dragons on each of its rising ridges. On the apex of the roof you’ll find the famed ‘Sanxing’ (三星) deities Fu, Lu and Shou (福祿壽) who are considered to the be embodiment of ‘Fortune’ (福), Prosperity (祿), and Longevity (壽), and are commonly found on temple roofs all across Taiwan. You’ll also find other cut-porcelain carvings (剪瓷雕) along the roof, which have become indicative of traditional Hokkien-style architecture in Taiwan.

Links: Sanxing | 三星 | Hokkien Architecture | 燕尾脊 (Wiki)

It’s not often that I actually learn new words when I write these articles, but as you enter the temple you are met with an area reserved for prayers referred to as a ‘Chuan-tang prayer pavilion’ (川堂拜亭), admittedly a loose translation.

This part of the temple features an area where guests are free to sit on one of the provided cushions to worship the City God. The reason why I’m learning a new word here is due to the fact that these prayer areas aren’t as common in temples anymore as most people complete their prayers while standing.

Coincidentally in a lot of temples, this particular area would be a roofless court-like area that allows for natural light to come into the temple and the burning incense to leave. However, as this is a City God Temple, it differs in its design as temples like this are traditionally constructed to be a bit ‘darker’ than your average temple, creating what should be a more solemn and mysterious space like that of a governmental office.

With this in mind, you’ll probably also notice that the elaborate designs and bright gold decorations that you find in other Taiwanese temples aren’t utilized here as the City God prefers a much more subtle throne room given that he has little use for luxurious decorations.

Taking into consideration that there is an open space along the eastern and western walls between the Front Hall and the Main Hall, its important to take note of the network of pillars located between the ‘Chuan-tang’ pavilion and the Main Hall. In total there are eight stone pillars, with four on each side, and while they are decorative they serve a more functional purpose in helping to keep the roof above in place.

Once you’ve passed through the Main Hall and go to the rear, you’ll find a much more open space and brighter space featuring an open roof that allows an ample amount of natural light into the rear shrine room. One of my favorite features of the rear hall though isn’t its more bright and spacious design but the round open passage doors along the eastern and western walls. These round doors can be found in some of Taiwan’s older places of worship, but it is an architectural design that has been lost over time, which is a shame.

Although the rear hall is a lot more spacious and brighter, it is also a bit cramped as it features three shrines in the center, with two more to their sides and another against the wall. With more than eighteen deities featured within the rear hall, its spaciousness can also come across as a bit busy, especially if there are a lot of people visiting.

Finally, if you continue walking beyond the rear hall to the back of the temple you’ll come across something that is quite odd in Taiwan - grass!

The temple is home to a ‘backyard’ of sorts where there is a very nice public washroom, and a large paper burner next to a garden with grass and a beautiful Chinese-style open air pavilion. The area is quite nice, but with the recent construction of a luxury apartment building to the rear of the temple, the view from the garden isn’t as nice as I’m sure it used to be.

That being said, if you’re doing a walking tour of the area and require a nice washroom to relieve yourself, I highly recommend this one!

While this is more of a general description of the architectural design of the temple, I do want to focus on a few of the decorative elements that really stand out. If you visit, it’s important that you take note of these things as they’re important cultural relics here in Taiwan.

Stone and Wood Carvings (石雕/木雕)

While the temple might differ from other temples in Taiwan with regard to its decorative elements, it’s important to note that the major difference is that it doesn’t go over the top. The decorative elements in the temple are subdued, but also aged at the same time. So while you don’t experience the over-saturation of color that you get at most temples, if you pay close attention, you’re going to notice that there is considerable artistic mastery on display throughout the temple, but the devil is in the details, and you really have to take some time to notice it.

With regard to the stone carvings, you’ll want to pay attention to the pillars mentioned above, each of which feature stone carvings. Located between the Middle Door at the front entrance you’ll find two beautifully carved dragon pillars and several murals along the walls nearby.

Likewise along the eastern and western walls between the Front Hall and the Main Hall you’ll find two large murals of a dragon (天井龍堵石刻) and a tiger (天井虎堵石刻). The murals position, following the tradition of the ‘dragon’ door and the ‘tiger’ door with the dragon on the right side and the tiger on the left.

When it comes to the wooden carvings, you’ll have to look to the sky to find them. The wooden carvings, which have been masterfully crafted are located along along the network of trusses and beams that help to keep the roof in place and distribute its weight. You are going to find various designs within the carvings, which are usually of ancient Chinese mythical creatures, but are all really beautiful and have been part of the temple for hundreds of years.

The most obvious of all the wood carvings, or at least the one that is at eye-level is the beautifully crafted wooden panel window (木雕門版) on either side of the middle door. When it comes to these hand-carved wooden panel windows, they’re somewhat of a dying art in Taiwan, and in most cases you’ll find them today made of cement, which is a shame.

For foreign visitors looking at the mural, you might think its just a hodge-podge of images, but in actuality both murals, if put together are telling the story of the ‘Eight Immortals Crossing the Sea’ which is one of the most popular Taoist myths.

Link: The Eight Immortals Cross the Sea (The Daoist Encyclopedia)

The Iconic Plaque (爾來了匾額)

As soon as you enter the temple, you’re met with one of it’s most well-known, and highly-regarded decorations, the “You’re finally here!” plaque.

Considered to be one of Tainan’s ‘four famous plaques’ (臺南四大名匾), it is one of those things that most locals in Taiwan are aware of, even before they visit the shrine as it is often covered in history textbooks in Taiwan’s schools.

For reference: The other three plaques are: 「一」at Tiantan Temple (天壇), 「了然世界」at Zhuxi Temple (竹溪寺), and「大丈夫」at the Martial Temple (祀典武廟).

The black plaque features beautiful golden calligraphy that, as mentioned above, translates as “You’re finally here!” (爾來了) a phrase that is used somewhat ironically, or in a condescending tone.

The reason for this is quite simple - the City God is pretty much always watching you, and he knows the good things you’ve done, as well as the bad. For westerners, I guess this is comparable to Santa Claus, but unfortunately for children Santa doesn’t have a temple where you can go to apologize for your transgressions. As a judicial deity, the City God has control over Yin and Yang (陰陽), and its his role to deal out demerits for any karmic misdeeds in your life.

So, when people arrive and see this beautiful plaque, its a reminder that you not only have to be a better, more righteous person. You should likewise come often to confess those sins to the City God so that when you pass away, your demerits don’t outweigh the good things that you’ve accomplished.

The Abacus (大算盤)

Located in the rafters directly opposite the plaque, you’ll find a giant abacus, which is another one of the most important decorative elements of the temple. Considered to be one of the City God’s most important tools upon which he comes to a conclusion about a person’s life, the abacus is a reminder to people, like the plaque, that you should always be on your best behavior.

Both the plaque and the abacus were donated to the temple upon the completion of a major restoration project in 1937

Door Gods (門神)

The Door Gods at the shrine are classified as“Martial” (武將) and “Literary” (文官) with Qin Shubao (秦瓊) and his counterpart Yuchi Gong (尉遲恭) located on the middle door (中門). Qin is the lighter-skinned man carrying a sword while Yuchi has dark skin and carries batons.

The two figures are legendary figures who lived the Tang Dynasty (唐朝), and are commonly displayed as door gods on temples thanks to a story that explains how they once stood guard at the door of the emperors bedroom to protect him from angry ghosts, allowing him to rest peacefully.

On the Dragon Door (龍門), you’ll find a ‘Eunuch’ (宦官) holding a peony and an incense burner while the Tiger Door (虎門) on the other side features a ‘Palace Lady’ (宮女) holding a teapot. Both of these door gods are used to indicate that there is a royal palace on the inside.

Even though the temple itself is hundreds of years old, these beautifully painted Door Gods only date back to 1976 when they were repainted by famed Tainan artist Phuann Lē-tsuí (潘麗水), whose work can be viewed all over Taiwan today in many of the nations most important places of worship.

Link: Pan Li-shui's art (The Bradt Taiwan Taiwan Guide)

Getting There

Address: No. 133, Qingnian Rd., West Central Dist., Tainan City (臺南市中西區青年路133號)

GPS: 120.20906/22.991987

Located a short distance from Tainan Train Station, getting to the City God Temple is relatively easy if you’re coming from out of town.

That being said, if you’re staying closer to some of the city’s larger attractions like the Confucius Temple, or Chikan Tower, there is a bit of a distance between them. Unfortunately, given the temple’s proximity to the railway station, there aren’t too many buses available that will bring you directly to the temple.

Train / High Speed Rail

If you’re taking a train to Tainan, the temple is less than a ten minute walk away from the railway station, so if you’re not carrying too much with you, you’ll probably just want to make your way on foot. To get there, you’ll turn left from the station front and walk down Beimen Road (北門路) until you reach Qingnian Road (青年路) where you’ll turn right and walk until you get to the temple.

If you’re arriving in Tainan from the High Speed Railway Station (台南高鐵站), you’ll have to first take the free shuttle bus to the Tainan Railway Station and then follow the steps above.

Bus

Most local travel sites recommend you take Bus #2, 5, 6, 7, 15, 19, 25, or 26 and get off at the Tang Te-chang Memorial Park bus stop (民生綠園站) and either walk or take a taxi from there. One thing you’ll want to note is that the park itself is located within a traffic circle, so when you get off the bus you have to be careful about which direction you head in when you are making your way toward the temple.

Link: Tainan City Bus Website

Scooter / Bicycle

While in Tainan you unfortunately won’t have access to Youbikes like other cities around the country, but the city has its own version called “T-Bike,” which you are encouraged to make use of during your visit. Likewise, if you have a drivers license you can also sign up for the convenient GoShare scooter service that’ll allow you to cheaply scoot around the city.

As is the case in most of Taiwan’s large cities, you’ll also find scooter rental shops near the railway station where you can rent a scooter for the duration of your stay. The prices per day are usually pretty fair, but if you don’t have a local license, you might be refused.

If you’re asking me, Tainan is a very walkable city and one of the best things about a visit to the city is that as you walk around town you’re able to find so many secret crevices in alleys that are hidden from your average tourist. With a distance of less then 10-20 minutes walking from anywhere you’ll want to visit in the historic district, you’ll certainly enjoy your visit better if you walk.

While in Tainan, you’ll also want to check out the Koxinga Shrine (延平郡王祠), the Confucius Temple (台南孔廟), and the Tainan Martial Arts Hall (台南武德殿), all of which are nearby. Likewise, you may have already heard that it’s pretty much the culinary capital of Taiwan, so if you are wondering where or what to eat, I recommend checking out this article about how to Eat Like a Local in Tainan to help guide you through the city.

Hours: Open daily from 06:00 - 21:00

References

臺灣府城隍廟 (TW CITY GOD)

臺灣府城隍廟 (Wiki)

臺灣府城隍廟 (Taiwan Gods)

臺灣府城隍廟 (Taiwan Digital Archives)

臺灣府城隍廟 (臺南宗教藝術)

臺灣府城隍廟 (台灣文化部)

臺灣府城隍廟 (台南咬一口)

台南-台灣府城隍廟 (Just a Balcony)

台灣城隍廟{二} (台南顯佑堂安溪城隍爺的部落格)

Taiwan Fu City God Temple (TW CITY GOD)

Taiwan City God Temple / 臺灣府城隍廟 (Travel Tainan / 台南旅遊網)

City God Temples (Premier Hotels)

Chenghuang—City God, Judge, and Underworld Official (Digital Taiwan)