Leprosy was always one of those things we knew about as kids, but never experienced first hand - We all heard the bible stories of Jesus healing lepers and after the disease was eradicated in most developed countries it became somewhat of a 'joke' that a person who had the disease was likely to have random body parts fall off at any given moment. It was easy to laugh at jokes like that because we didn't really understand and would never have to experience the disease in the way that past generations had.

When I visited Nepal a few years back I saw the disease up close for the first time and the experience shifted a lot of what I thought about leprosy and those jokes just didn't seem funny anymore. The disease may have been eradicated in the developed world, but in developing countries were poverty is more prevalent, the disease still rears its ugly head afflicting people who cannot afford treatment. The World Health Organization has done some great work offering free multi-drug treatments to people in impoverished nations, but while the problem isn't as bad as it used to be, it still exists and is still common in places like India and Nepal. The good news however is that we have reduced the amount of cases worldwide over the past decade from around five million to less than 150,000 and with luck we will be able to completely eradicate the disease in the near future.

One of the major problems with leprosy is the social stigma that goes with it; Leprosy is a contagious disease, but it isn't as contagious as most people think it is and the possibility of contracting it from a family member isn't that high. Unfortunately before this discovery, people with leprosy, or "lepers" as society had dubbed them were put in institutions to isolate them from the general public.

Sanitariums (sanatoriums) were thus set up as long-term care facilities for people with leprosy (and other diseases) which required long-term treatment or as a hospice for people so gravely ill that they would likely never leave again. Realistically though, the main purpose of most of these hospitals was to keep these people away from the general population in an attempt to stop the disease from spreading. The term "leper" these days still carries quite a large social stigma and if you search the word on urban dictionary you're likely to come up with dozens of results and I'm quite sure that English isn't the only language which stigmatizes the word in this way.

The concept of a "sanatorium" hits pretty close to home as one of the most important people in my life, my stepdad, was forced to live in one in his youth. A simple medical checkup for an application to join the Canadian armed forces revealed that he had tuberculosis, so instead of joining the army he had to live in a sanatorium for over eighteen months instead and wasn't allowed to leave until he was cured. He rarely mentioned the experience while I was growing up and I'm sure that it was an experience that he would much prefer to not think about it at all which is why it was best for us to never really ask him about it.

The Losheng Sanatorium (樂生療養院) in the Xinzhuang district (新莊區) of New Taipei City is one of these special types of long-term care facilities which had a mission to treat the people of Taiwan who had contracted leprosy. It was constructed over eighty-five years ago during the Japanese colonial era and was originally named the Rakusei Sanatorium for Lepers of Governor-General of Taiwan (臺灣總督府癩病療養樂生院) and later renamed when the colonial period ended. The complex has been the subject of heated debate on one side due to its historical value and on the other for the strategic development area it is located in. It is also quite popular with urban explorers as the original hospital has been abandoned for years despite a small community of people who remain in the area around the hospital and have been reluctant to leave.

Losheng (樂生) which translates as "Happy Life" was built in 1929 by the Japanese to house and treat people suffering from leprosy - At the time the disease was considered highly contagious so it was common practice to isolate these people from the general population. The hospital and the community around it was built on a mountain and was set up to be a self-sufficient 'village' where people could take care of all the necessities of life without having to leave. It was built on the side of a mountain bordering what is now Taoyuan county's Gueishan township (龜山區) and was complete with gardens, farms, temples, churches, etc. At the time of its construction, it was probably quite progressive for the Japanese, a colonial power, to build such a beautiful sanitarium equipped with modern medical facilities allowing the people who were forced to live there to live a "happy life" while in isolation from their families and rest of the island. The fact that it was built on the side of a mountain however made escape a bit difficult and I'm sure that was also taken into consideration before its construction.

Fortunately, the need for such a sanatorium became pointless in the early 1950s as new developments in medical treatment became available helping to cure people of the horrible disease. Therefore in 1954 the compulsory isolation of people suffering from leprosy ended and people were free to leave and rejoin society. Unfortunately social stigma and discrimination persisted as the appearance of those who were afflicted with the disease often made it difficult for them to re-assimilate back into society. This led to a lot of people making the decision to live out the rest of their lives in the community where they felt safe and obviously where they had become so familiar with.

As of 2006, the number of residents living on the compound numbered only around 200 with 162 living in a new nearby hospital (迴龍醫院) and 52 on the compound itself. The old sanatorium has been abandoned and a new modern hospital has taken over treatment. The government made plans to completely demolish the ruins of the old hospital to make way for development of a depot for Taipei's Mass Rapid Transport (MRT) system's Orange Line (中和新蘆線) which has already started operation and will eventually expand further connecting residents to new parts of the city as well as Taoyuan county and the airport. These plans have met with resistance from civic groups and members of the community who argue that the hospital and the community around it are important and should be preserved for historical and cultural value. Unfortunately in Taiwan, development is often much more important than historical preservation.

The MRT depot is currently under construction near the abandoned hospital, but the project met with large-scale protests in 2007 that pressured the government into changing its policy with regard to the sanatorium. After years of lobbying and protests, the government agreed that 39 buildings within the community would be preserved, 10 reconstructed and 6 would be demolished. This meant that while the community would continue to exist and that some conditions would improve, they would have to accept the loss of some of the original buildings as the MRT depot was important for the future plans of the MRT system.

The sanatorium currently still stands in its original location and despite being abandoned and in some parts run-down, it is still in pretty good shape. The engineers working on the depot have had to build a wall on the mountain to protect the hospital from erosion and a lot of the buildings have tarp covering them due to damage to the roof. It has become a popular place for urban explorers to visit and while it isn't anything compared to what my good friend Alexander Synaptic discovers, it helps to act as an introduction to the hobby and spark an interest for further exploration. The hospital has also become popular with local photographers as a place to have spooky photo shoots.

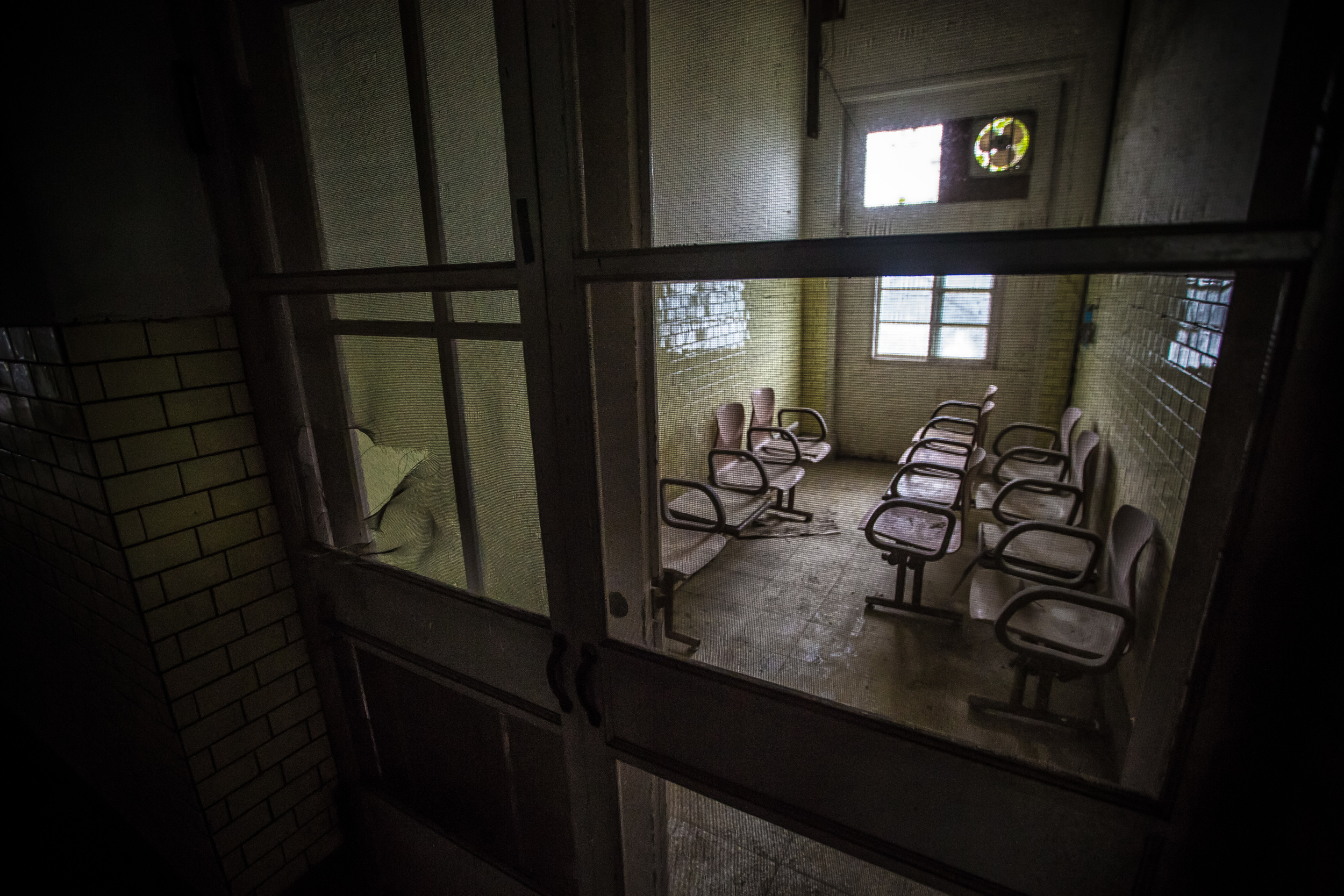

The hospital has some pretty cool rooms that are extremely capable of freaking out any of your superstitious friends. There is a surgery room, a morgue, an X-Ray room, old offices, doctors dormitories, patient rooms, recreation rooms, a library and long dark passages that tend to scare quite a few people. The rooms are full of old paraphernalia including Microsoft Office 97 discs, MS-DOS books, floppy disks, old records, cassettes and VHS movies as well as various belongings that were randomly left behind when the hospital closed. Some of the rooms are full of clutter while others are clean and neat. It's interesting to stop in the rooms and look at stuff that was so common in the 80s and 90s that we don't really think of any longer.

I'm not really a superstitious kind of guy, but on my second visit, I walked alone around the hospital on a grey day with the rain hitting the roof and dripping in through various holes. The light was terrible and it was dark inside. I'm pretty sure that if any one jumped out and screamed that I'd probably have a heart attack. On my way out I ran into an old resident of the community on a motorized wheelchair. He stopped in front of me and smiled and said hello. I stopped and greeted him and immediately noticed his disfigured skin and missing fingers. The man was smiling and happy to meet someone walking through his community so I took a few minutes out of my day to have a conversation with him. When the rain picked up he said goodbye and scooted off back to his home. If it were my first experience with leprosy I might have had a different reaction, but I'm happy that I was able to have a quick conversation with someone who probably doesn't have the opportunity to get out and enjoy his senior years as often as he should.

Taiwan is a country full of history, but sometimes that history isn't always well-preserved and visiting a place like this helps us to understand the way things were in days gone by. I'm sure when the renovation and reconstruction projects are finished that Losheng will become a popular attraction for tourists to visit and learn about the historical value of such a place, but right now, I prefer to enjoy it the way it is.

If you have any questions, comments or criticism, don't be shy - Comment below or send an email through my contact section below!

Getting There / Map

In most cases with an Urban Exploration post, I wouldn't share the location in my blog post. When it comes to Losheng Sanatorium however, information about its location is easily accessible in both Chinese and English, so I figure letting people know how to get there isn't really a big deal.

The Sanatorium is easy to get to and is accessible through the Taipei MRT system. To get to the Sanatorium, take the MRT to Huilong Station (迴龍捷運站) and from Exit 1 (1號出口) walk down Wanshou Road (萬壽路) until you arrive at Huilong Temple (迴龍寺), walk up the hill to the new hospital and across the bridge to the rear where you'll find the former sanatorium and the community around it.

Gallery / Flickr (High Res Shots)