From the perspective of a foreigner living in Taiwan, I have to say that this country can a be a bit weird when it comes to it’s fads; If you’ve been in the country over the past couple of years, you’re likely to have noticed a sudden obsession with claw machines - almost every city, town and village across the country has been rather annoyingly been overrun with the noisy machines. Similarly, when it comes to food, we’ve gone through periods where you’d find a sudden influx of hamburger, pineapple buns and egg tarts places making a quick buck, before closing up shop and moving onto the next sensation.

When it comes to tourist destinations, social media trends tend to drive most of the interest in specific locations, but one of the more noticeable tourist fads in recent years has been with the appearance of a bunch of newly constructed suspension bridges in picturesque mountain areas.

I can’t particularly speak to the motivations for building these bridges, or their popularity, but with recent trends in domestic tourism shifting toward getting out and enjoying the natural beauty of the country, you’ll discover that mountain destinations are likely to be packed with weekend tourists, looking for something new to do!

That being said, some of the suspension bridges that have been making an appearance as of late aren’t actually all that ‘new’. Sure, you’ll find some that have glass floors, constructed with modern engineering techniques, but in a lot of cases they’re just modern replacements for a much older bridge.

Case in point, the bridge I’m going to be introducing today!

Before I start introducing the bridge, I should take a minute to explain something, especially since this is the second article I’ve published covering a suspension bridge in the mountains of Taoyuan in recent months.

Have I succumbed to the suspension bridge fad? No, I promise you I haven’t.

There’s a reason why I’m writing about these popular tourist spots.

Basically, these articles are meant to be an extension of the work I published in my article, The Daxi that Japan left behind (日本留下的大溪), where I’ll be continuing my research on the development of Taoyuan during the Japanese-era, with Daxi acting as the processing centre for much of the natural resources taken from the mountainous areas. In the next few months I’ll be publishing further work that focuses on the various aspects of the mountainous village of Jiaobanshan (角板山), known during the Japanese-era as Kappanzan (カッバンソァン), where this suspension bridge is located.

So, even though this bridge was completely reconstructed a few years ago, it has also been an important part of the village for the better part of a century, connecting two sides of the Dahan River (大漢溪). and the communities that existed on both sides for well over a century!

Xikou Suspension Bridge (溪口吊橋)

The ‘Jiaobanshan’ area as it is known today has been home to sparse groups of Atayal Indigenous tribes (泰雅族) for hundreds if not thousands of years, referring to it in the their native language as “Pyasan” (北亞山).

Having settled in the area for so long, you might be surprised to learn that the majority of the tribes that exist in Taoyuan’s Fuxing District (復興區) today have actually only occupied space there since the late 1800s.

In fact, many of the ‘tribal areas’ that have been set up in the district today were forced to resettle there as they were forced to abandon their homes in the nearby mountains of Wulai-Sanxia (烏來-三峽) when the Qing started encroaching on their lands, and then following with the arrival of the Japanese in Taiwan.

Despite armed resistance against both the Qing and Japanese forces, the Atayal people suffered considerable losses, and ultimately succumbed to resettling in areas much deeper in the mountains where they thought they’d be safer.

One of those resettled groups were the Rahaw (拉號), known in Mandarin as the Xikou Tribe (溪口台部落), who settled on the remote opposite side of the river from Kappanzan, which was developed early on during the Japanese-era for the extraction of camphor and tea. Living on the other side of the river, the tribe likely figured that they’d be left alone, but the Japanese had other ideas.

Marching into the area with an armed force of over two thousand soldiers in 1907 (明治40年), the colonial government sought to pacify Indigenous resistance to their rule, and for a three month period the army advanced from Abohei (Amuping / 阿姆坪) all the way to Kappanzan, following the river, in what would become known as the Chinto-zan Conflict (枕頭山戰役).

Once the area was firmly under Japanese control, construction started on a number of facilities dedicated to ensuring the efficiency of the extraction of natural resources from the mountains.

Ironically, with major hostilities at an end, and taking into consideration the importance of Taiwan’s mountainous areas for the colonial government’s extraction of natural resources, initiatives were taken to attempt a ‘softer’ approach to the sword in dealing with Taiwan’s Indigenous people. Doctors, dentists and educators sent to Kappazan ((and other predominately indigenous areas around the island) and schools and medical stations were constructed in an attempt to usher in ‘improvement’ in the quality of life for these groups.

Of course, it should go without saying that this farcical ‘softer approach’ wasn’t entirely altruistic, as much of the educational system was meant to erase Indigenous cultural values, traditional customs and identity.

At the same time, scientists came to the area looking for breakthroughs in the cultivation of cinchona (金雞納樹), a flowering plant known for its medicinal value, especially with regard to treating malaria, which was a huge problem in Taiwan prior to the arrival of the Japanese.

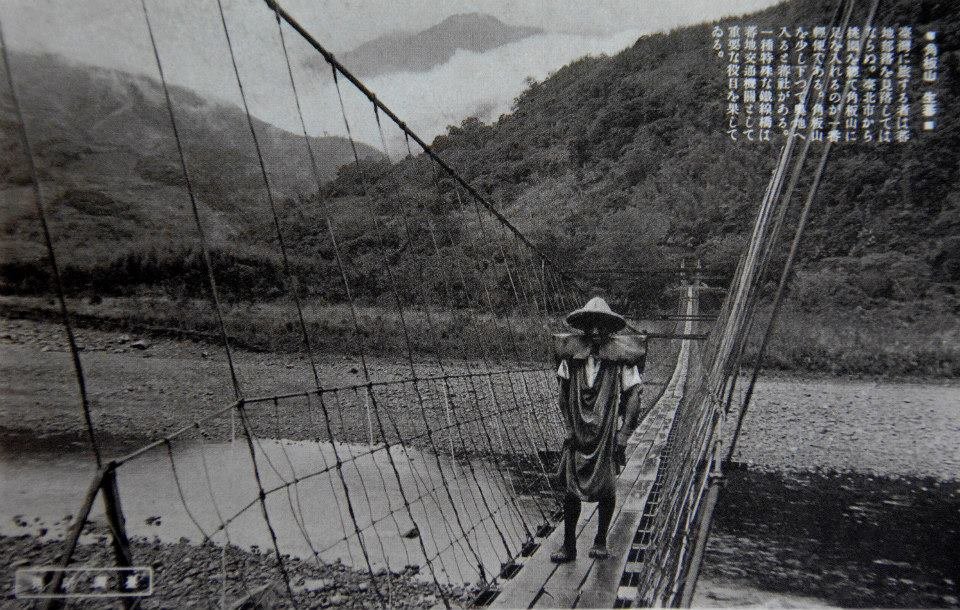

In 1922 (大正11年), construction on a steel suspension bridge that spanned the Dahan River was completed, connecting Kappanzan to the tribe, known at the time as ‘Raho-sha’ (拉號社). Referred to by local historians as the ‘First Generation Xikou Suspension Bridge’ (第一代溪口吊橋), the bridge brought economic opportunity to the tribe soon after its completion as engineers constructed a genius irrigation system on the plateau for the cultivation of rice.

When Super Typhoon Gloria (颱風葛樂禮) swept through northern Taiwan in the summer of 1963 (民國52年), it left a considerable amount of damage and hundreds dead in its wake. Another of its victims was the suspension bridge, which once again cut off the Rahaw from the community in Jiaobanshan.

Soon after, the Second Generation Xikou Suspension Bridge (第二代溪口吊橋) was constructed for the ‘benefit’ of the tribe across the river, which was gifted the unfortunate nickname the ‘Presidential Tribe’ (總統部落) due to President Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) affinity for the area. (He had a villa in Jiaobanshan).

The newly bridge had an improved capacity of fifteen people at a time, and was used from 1963 until 2015, when it was dismantled to make way for the third generation bridge, a much grander version of it’s predecessors.

Xinxikou Suspension Bridge (新溪口吊橋)

The latest version of the Xikou Suspension Bridge opened to the public in January 2018, measuring at a length of 330 meters, and is (currently) the nation’s longest suspension bridge. Located next to where the original bridge was located, the new version is almost double the length, and is 23 meters above the river, much higher of the original. Where the second generation bridge could only safely sustain about fifteen people at once, the new bridge can easily accommodate more than a hundred, and is wide enough for people to walk back and forth, rather than single file.

By 2010, it was decided that after a half century, the old Xikou bridge had become far too unstable after years of abuse to continue using for much longer, so the Taoyuan City government came up with a plan to replace it for the third time. This time however, the focus would be on providing a more enjoyable experience for the locals, while also creating a new tourist destination in the mountains that would compliment Jiaobanshan Park (角板山公園).

Instead of referring to it as the 'Third Generation Xikou Bridge’, authorities decided instead to call it the ‘Xinxikou Suspension Bridge’ (新溪口吊橋), which is just the romanized pinyin version of “New Xikou Bridge,” which if you ask me is a bit of a head-scratcher. If it were up to me, I would have taken the opportunity to just rename it completely to better reflect the Indigenous community that it serves, but apparently no one thought about that.

Nevertheless, where the bridge does reflect the Atayal Indigenous community is in its color scheme and the designs along the sides. Likewise, the side opposite of Jiaobanshan currently features a Tribal market (溪口部落市集廣場), where you can sample some local cuisine (mixed in with typical night market fare) as well as stalls set up to sell arts and crafts, allowing the local community to benefit from the increased tourism in the area.

In Mandarin, the bridge is known officially as a hammock-style suspension bridge (懸吊式吊橋), in engineering terms, its technically an ‘underspanned suspension bridge’ in that it is anchored deep into the ground on both sides with cables spreading out (in a hammock-like fashion) across its underbelly, with the deck raised on posts above. With this type of bridge, visitors are better able to enjoy the beauty of the natural environment without a bunch of cables getting in the way, but it is a less stable engineering style that does allow for a bit of rocking back and forth when people are walking across the bridge.

As an extension of the Jiaobanshan Park, which attracts quite a bit of weekend and holiday tourist traffic, most people visiting the bridge are going to do so from that side of the river. Jiaobanshan however is located on a plateau high above the river, so there is a bit of a nature hike involved if you’d like to cross the bridge.

The tree-covered walk is a nice one, but there are quite a few stairs, so once you walk down and cross the bridge, it’s actually really great that there’s an Indigenous market on the other side where you can buy some snacks and drinks before heading back up the hill.

When the bridge first opened to the public a few years back, it was so popular that an online reservation system had to be set up to ensure that long lines of cars wouldn’t be clogging up the narrow mountain highway. Thankfully, some of that popularity has died off as time has passed, so if you are visiting the area today, you shouldn’t have much problem checking out the bridge.

Oh, and before I finish, I should probably let you know that if the weather is cooperating on the day of your visit, you’re going to be rewarded with some pretty spectacular mountain landscapes with the beautiful turquoise Dahan River (大漢溪) flowing below. You may notice that I’m sharing photos from two different visits to the bridge. On my first visit, the bridge was closed (due to COVID protocols), and the river below was pretty much empty due to a massive drought that we were having at the time. I was much luckier on my second visit as the bridge was open, the weather was perfect and the river was flowing beautifully.

If you have the opportunity to visit, I hope you’re lucky enough to go on a beautiful day!

Hours: Wednesday - Monday (8:00 - 15:30)

Admission: $NT 50 per person.

Website: 新溪口吊橋 (Facebook)

Getting There

Address: #8 Zhongshan Road, Fuxing District, Taoyuan. (桃園市復興區澤仁里中山路8號)

GPS: 24.814489, 121.350792

The great thing about bridges is that they connect two sides of a river, right?

Well, that’s ironically also the confusing thing for a lot of tourists who want to visit this bridge.

You can access this bridge from either the Jiaobanshan (角板山) side, or the Xikou Tribe (溪口部落 / Hbun Rahaw takan) side, with a list of pros and cons for both. For anyone taking public transportation to the area, you’re going to be forced to visit the bridge from the Jiaobanshan side, which features the steep walk down a set of stairs to the bridge mentioned above, something you’ll have to repeat when you’re done.

On the other hand, if you have access to your own means of transportation, you have the option of starting from the opposite side of the river, but parking on that side is more expensive, and spaces are limited, so you may end up having to wait in line on weekends.

That being said, parking within the Jiaobanshan area can often be difficult to find and expensive as well.

If you’re driving a car or scooter you have the choice of parking anywhere within Jiaobanshan and walking the rest of the way to the bridge. If you choose to start from the other side, you’ll have to pass by Jiaobanshan and continue along the Northern Cross-Island Highway (北橫公路), crossing the Fuxing Bridge (復興大橋) into Luofu Village (羅浮), where you’ll make a right turn onto the famed “Roman Road” (羅馬公路) on your way to the Xikou Tribal area, finally stopping at the Xikou Tribe Cultural Square (溪口部落文化廣場).

The address here is different than the one provided above, so to make your way to the bridge on the opposite side, I recommend inputting this address into your GPS or Google Maps:

Address: #59-1 Xikoutai, Fuxing District, Taoyuan (桃園市復興區澤仁里4鄰溪口台59-1號)

Public Transportation

If you don’t have access to your own means of transportation, there are a few different bus routes that you can take from the Daxi Bus Station (大溪客運站) to get to the area. In each case you’ll take the bus from Daxi all the way to the Fuxing Station (復興站) within Jiaobanshan Village and from there you’ll walk to the trail that brings you to the bridge.

For those of you unfamiliar with the Daxi area, you’ll also have to find public transportation to get to the bus station there. There are a number of options for taking the bus to Daxi either directly from the railway stations in Taoyuan or from Taipei. I’ll provide each of the buses that you can take below with links to where you can find the bus, their route map and their schedule.

Taoyuan Bus (桃園客運) #5096 (Taoyuan - Daxi / 桃園 - 大溪)

Taoyuan Bus (桃園客運) #5098 (Zhongli- Daxi / 中壢 - 大溪)

Taoyuan Bus (桃園客運) #9103 (Banqiao - Daxi / 板橋 - 大溪)

Taoyuan Bus (桃園客運) #710 (Yongning MRT Station - Daxi / 永寧捷運站 - 大溪)

Taiwan Trip Tour Bus (台灣好行) #501 (Taoyuan HSR Station - Daxi / 桃園高鐵站 - 大溪)

Links: Taoyuan Bus (桃園客運) | Taiwan Trip Shuttle (台灣好行)

The Xinxikou Suspension Bridge is just one of a long list of interesting tourist destinations within the Jiaobanshan area in addition to nearby Xiaowulai (小烏來). If you find yourself in the area on a day-trip, I highly recommend you stop by to check out the bridge, which (if the weather is cooperating) can be a beautiful experience. You’ll want to make sure to check out some of the other cool places to visit while you’re in the area, and I recommend you take some time to try some of the Indigenous fried mushrooms and peach smoothies when you’re in town!

I’ll have quite a bit more about the area over the next little while, so watch this space if you’re interested in what the area has to offer!

References

新溪口吊橋 (桃園觀光導覽網)

溪口吊橋 (Wiki)

溪口吊橋 (國家文化記憶庫)

新溪口吊橋‧站在台灣最長的懸索橋欣賞大漢溪谷的風光 (旅遊圖中)

【桃園】復興-羅馬公路:溪口台部落 (湘的部落格)

臺灣國定古蹟編纂研究小組 (National Historic Monuments of Taiwan)