If it weren’t already obvious enough, I’m a big fan of living in Taoyuan.

I take a lot of online abuse for being one of the city’s biggest proponents, but even though I do love other areas of Taiwan like Taipei, Hsinchu and Tainan, I couldn’t ever see myself actually moving to any of those places on a full time basis. I’d miss home too much! There is of course a long list of reasons why I love living here, but I’m not going to list all of them here today.

I will however be highlighting one of the areas I absolutely love visiting whenever I have some free time. Coincidentally, it is also the same place that most Taiwanese think about whenever considering coming to Taoyuan for the day - Daxi Old Street (大溪老街).

There has always been a healthy, yet contentious debate in Taiwan with regard to which “Old Street” or “Night Market” is the best, with most people claiming the one located closest to them is the best, but I think in the case of historic tourist streets, Daxi was crowned the undisputed champion long ago. Not only does the street feature absolutely beautiful art-deco baroque architecture, but it also serves up some pretty amazing food to visitors and offers daytrippers a number of other things to see and do, making a trip to Daxi one of the best day trips in northern Taiwan.

And yeah, I might be accused of playing favorites considering where I live, but I count myself lucky that I can simply ride my scooter over, park in an alley and go exploring whenever I feel like it, avoiding the weekend traffic and massive crowds of tourists.

I suppose you could say that one of the benefits of being a resident of Taoyuan is that I often get to see a part of Daxi that most of the weekend visitors miss. So while most people stick to the popular Old Street, known as “Peace Street” (和平街), there are a number of quiet alleys and lanes throughout the downtown core of the village that feature the same style of century old architecture, but are home to hip new cafes and restaurants.

The Taoyuan City Government likewise has invested heavily in the restoration of historic buildings in Daxi, which is helping to diversify tourism as well as providing people with an ever-growing number of things to see and do while visiting the area. Of particular interest (for me at least) are the restoration projects that have revived the Japanese administrative quarter of the town, which is as much a part of the history of the village as the historic old street itself.

Not only is Daxi home to one of Taiwan’s most beautiful Japanese-era Martial Arts Halls, there are also a number of other buildings within the village (and nearby as well) that have been beautifully restored and reopened to the public as culture parks - all of which allow people to learn more about the compelling history of this small, yet extremely important little village.

Today I’ll be offering a general introduction to some of these recent Japanese-era additions to the Daxi tourist scene.

In the future I plan to use this space to link to individual articles about each of these buildings, but that’s going to take a bit of time as there is still a lot of restoration work ongoing in the area.

But before I get into any of that, let me start by offering a brief introduction to Daxi and why the Japanese Colonial Era had such an impact on the small village nestled in the mountains of Taoyuan.

Daxi during the Colonial Era (日治的大溪)

During the Japanese-era, The Taoyuan City (桃園市) that we know today was merely just a district (郡) of what was known as Shinchiku Prefecture (新竹州 / しんちくしゅう). Located in the area south of Taipei, or Taihoku (台北州廳), Shinchiku Prefecture encompassed much of what we refer to now as Taoyuan-Hsinchu-Miaoli (桃竹苗), with the capital of the prefecture located in Shinchiku City (新竹市 / しんちくし).

As much of Taiwan had yet to really start development of anything larger than small settlements, the cities that we know today as Taoyuan (桃園), Zhongli (中壢), Zhudong (竹東) and Miaoli (苗栗) were simply classified by the Japanese administration as ‘districts’ (郡), and were essentially part of hierarchical subdivisions of the larger prefecture that could be further broken down into towns and villages.

Taoyuan County’s recent amalgamation into the supercity known as ‘Taoyuan City’ retains much of the original geographic boundaries found during the colonial era. That being said, the current city is divided up into thirteen “districts” (區) while the Japanese only used three: “Chuureki”, “Toen” and “Taike.”

The interesting thing is that within these Japanese-era “districts”, you’ll find each of the contemporary administrative districts that make up Taoyuan City today.

Chuureki (中壢郡 / ちゅうれきぐん), otherwise known as “Zhongli District” and included Zhongli (中壢街 / 中壢區), Pingchen (平鎮庄 / 平鎮區), Yangmei (楊梅庄 / 楊梅區), Xinwu (新屋庄 / 新屋區) and Guanyin (觀音庄 / 觀音區).

Tōen (桃園郡 / とうえんぐん), otherwise known as “Taoyuan District” and included Taoyuan City (桃園街 / 桃園區), Luzhu (蘆竹庄 / 蘆竹區), Dayuan (大園庄 / 大園區), Guishan (龜山庄 / 龜山區) and Bade (八塊庄 / 八德區).

Taikē (大溪郡 / たいけいぐん), otherwise known as “Daxi District” and included Daxi (大溪街 / 大溪區), Longtan (龍潭庄 / 龍潭區) and the mountain indigenous area we now refer to as Fuxing (蕃地 / 復興區).

Interestingly, the 1942 census (the final one taken during the Japanese era) reported that the population of the three districts of Shinchiku Prefecture mentioned above that make up what we know today as “Taoyuan City” was 288,740 - a fraction of the 2,245,059 people living here today.

The focus of this article however is on Shinchiku Prefecture’s district of Taikegun (大溪郡 / たいけいぐん), or what we refer to today as Daxi (大溪區). One of Taoyuan’s most popular tourist attractions, Daxi has long been a hotspot for Taiwan’s weekend travelers thanks to its beautiful Old Street, traditional Hakka culture, and of course its delicious food.

As I mentioned earlier, there are quite a few of these touristy ‘Old Streets’ in Taiwan, and one of the things that the vast majority of them have in common is that they date back to an era of prosperity during the Japanese colonial era, when Japanese architects were showing off their skill with contemporary art-deco baroque-style architecture. Daxi Old Street is no different and is highly-regarded throughout the country as one of the best preserved examples of the architecture of that era of Taiwan’s history.

It should go without saying that the history of Daxi as we know it dates back much further than the arrival of the Japanese in Taiwan.

Occupied several thousand years prior by Taiwan’s indigenous Atayal people (泰雅族), the area was long known as Takoham (大姑陷/大嵙陷) by those living along the creek that we refer today as the Dahan River (大漢溪). Then in the late eighteenth century, Han settlers started migrating to the area, helping to turn it into an important trading outpost. The early settlers made their riches extracting camphor and tea by way of the Dahan River and into Taipei via the Tamsui River (淡水河) where products would be sold and exported from the ports in Bangka (萬華), and later from Dadaocheng (大稻埕).

The history of Han settlement in the area, particulalry that of the Hokkien people (閩南人), who were forcibly pushed out of Taipei due to political and economic warfare between rival clans in the late nineteenth century, is certainly a juicy soap-opera-like situation that I highly recommend everyone learn more about.

Essentially, the events of the Ding-Xia Conflict (頂下郊拚) of 1853 helped to shape Taipei into the city it is today.

Links: Xia-Hai City God Temple (霞海城隍廟) | Qingshui Temple (艋舺清水巖) | Clashes in Monga a hundred years ago - Chronicles of the Gang Leaders of History (Digital Taiwan)

When the Japanese arrived in Taiwan in 1895, Daxi had already become a thriving town of merchants and traders, but that was a situation that would quickly change within a short period of time as the colonial government wasted no time getting to work on a network of railways around the island that would ensure a more efficiently and quicker transfer of goods than the rivers ever could.

By 1909 (民治42年), the west coast north-south mainline railway (縱貫線) between Taihoku (台北州) and Takao (高雄州) was completed and the need for river transport was pretty much nullified, dealing a major blow to the village as a major trading port. Fortunately, Daxi had more to offer than just its position as a trading port and the town made some changes that allowed it to maintain its role as an economic powerhouse. Continuing with the extraction of camphor, but also branching out into other areas with its production of tea, and the skill of local artisans in making handcrafted wooden furniture.

From the perspective of the Japanese authorities, Daxi was an extremely important village thanks to its ability to (safely) extract and transport camphor in addition to its production of tea, which surprisingly accounted for approximately seventy percent of Taiwan’s entire tea production at the time. So, even though Taikegai (大溪街 / たいけいがい) was considered a small ‘village’ within Shinchiku Prefecture, it had an established economic base and was a gateway to the mountains, which were instrumental in the colonial government’s plan for extracting Taiwan’s precious natural resources.

“Taikegun” (大溪郡), or Daxi District may have had its administrative district within Taikegai as mentioned above, but it was ultimately responsible for the administration of 577km² of land that likewise included neighbouring Ryutansho (龍潭庄 / りゅうたんしょう), and the mountain indigenous area (蕃地), known today as Fuxing District (復興區).

As an economic powerhouse, the colonial government dedicated a tremendous amount of resources in the area to ensure that the village’s economic vitality could continue. Thus, the government invested heavily in administrative infrastructure that included the construction of Administration Halls (役所), Post Offices (郵便局), Banks (銀行), Assembly Halls (公會堂), Public Schools (公校), Shinto Shrines (神社), Buddhist Temples (佛教廟), Police Stations, etc.

While the purpose of this article is to talk about the remnants of the Japanese era that can be found today in Daxi, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that even though the history of Daxi is long and complicated, the so-called Old Street that has become so popular with tourists only dates back to 1919 (大正8年), and almost everything that we see today is a result or influenced by the Japanese-era.

The Restoration of Japanese-era buildings in Daxi

Thanks to the leadership and foresight of the Taoyuan Cultural Affairs Bureau (桃園市文化局), there has been a revival in recent years with regard to Daxi’s Japanese-era history. The local government has invested a considerable amount of money in the restoration of many of these important historic buildings, and came up with a perfect way to put them to good use, highlighting an important part of what makes Daxi so special.

The Cultural Affairs Bureau officially inaugurated the Daxi Wood Art Ecomuseum (桃園市立大溪木藝生態博物館) on January 1st, 2015 (民國104年), a project that would emulate the Scandinavian concept of ‘integrating the local community with the preservation of cultural assets’ and today the museum encapsulates many of the historic Japanese-era buildings that have been restored in the historic administrative neighbourhood of the village.

Link: Daxi Wood Art Ecomuseum (Wiki)

In total, the ecomuseum is spread out across a network of buildings that includes the Japanese-era Assembly Hall, police and teachers dormitories, the Martial Arts Hall, and in the future will expand to include several more dormitories as well as a massive warehouse. Suffice to say, as time passes and the museum continues to grow, this space will likewise continue to be updated as well.

While the ecomuseum is primarily located within Japanese-era buildings, its important to note that the beautiful Lee Teng-Fang Historic Residence (李騰芳古宅) is also included in the list of buildings under the control of the museum.

Link: Official Daxi Wood Art Ecomuseum (桃園市立大溪木藝生態博物) - 中文 | English

I won’t go into detail to get into what you’ll find in each of the buildings exhibition-wise as I’ll leave that for future articles about those spaces, but as a “wood-art” ecomuseum, you’re safe to assume that you’ll find that quite a few of them proudly display the mastery that the people of Daxi have when it comes to woodworking, with displays of furniture, ornaments and other kinds of art.

I’m not personally too invested in that kind of thing, but there are fortunately also exhibits that focus extensively on the history of Daxi, and I could spend days checking them all out.

Without further adieu, here’s the list of remaining Japanese-era buildings and things to see while you’re visiting Daxi.

Daxi Assembly Hall (大溪公會堂)

As the only remaining building of its kind in Taoyuan, I’m happy to finally say that the former Daxi Assembly Hall has finally been brought back to life and returned to the public, for which it was dedicated to more than a century ago!

An important part of any large community during the colonial era, the Daxi Assembly Hall was constructed in 1921 (大正10年) and was a public meeting space and venue for local art and music performances. Constructed with a fusion of Japanese and Western-style architecture and construction methods, the hall is quite stunning in its design.

When the Second World War ended, the interior of the hall was renovated and it became a mansion for President Chiang Kai-Shek and his family when they were vacationing away from the capital. After his death, the hall was converted into the earliest ‘Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall’ (蔣公紀念館) and was opened up to the public for visits.

Not to be confused with the actual Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall (中正紀念堂) in Taipei, or his final resting place in nearby Cihu.

Today the hall has been split up into two exhibition spaces under the control of the Wood Art Ecomuseum, with the Wood Furniture Exhibition (木家具館) taking up the large space in the Assembly Hall while the Wood Life Exhibition (木生活館) is located within the extension on the side.

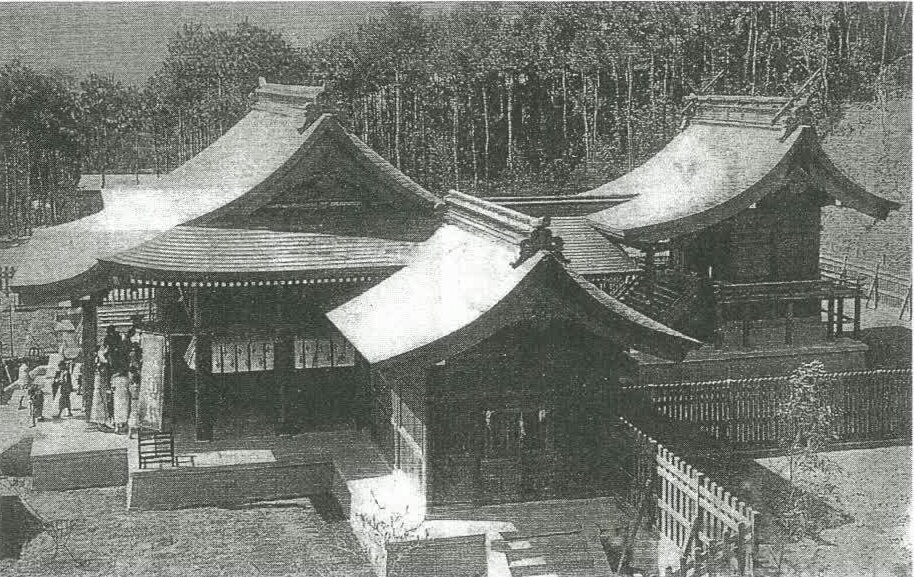

Daxi Shinto Shrine (大溪神社)

The Daxi Shinto Shrine (大溪社 / たいけいじゃ) was constructed in 1932 (昭和7年) and was located in the area where you’ll find the Daxi Park (大溪公園) today. Unfortunately the shrine was torn down in 1946 (民國35年, shortly after the arrival of the Chinese Nationalists.

Even though the shrine was destroyed, several pieces remain today, including the Walking Path (參道), Stone Lanterns (石燈籠), the Stone Guardian Lions (狛犬), and the original stone base where the Hall of Worship once stood.

Today you’ll find a several-layered tower constructed on the base of where the shrine once existed. If you climb to the top of the tower, you’ll easily be able to enjoy a nice view of the river basin and the historic Daxi Bridge that stretches across the river.

The area where the Shinto Shrine is located is well marked and you can easily walk over and check it out, it won’t take too much time.

Daxi Public School Principal’s Residence (大溪國小校長宿舍)

The Daxi Public School’s Principal’s Residence was the first of the Japanese-era dorms to open up to the public as part of the wood-art ecomuseum project. Known in Chinese simply as “Building Number 1” (壹號館), the building dates back to the 1920s and is a beautiful family-style dorm that would have been occupied by whomever was the administrator at the nearby Daxi Public School prior to the end of the war.

Today the building acts as an information centre for the Wood-Art Ecomuseum with exhibitions dedicated to the history of Daxi and woodworking in the area.

Daxi Martial Arts Hall (大溪武德殿)

The Daxi Martial Arts Hall is considered to be one of the most beautiful of the remaining Japanese-era Martial Arts Halls in Taiwan.

Constructed in a fusion of Western-Japanese style architecture, the building dates back to 1935 (昭和10年), and was used to help train the police and military who were stationed in the area in Japanese Martial Arts.

When the colonial era ended, the hall was repurposed as a police outpost for members of the Military Police who were charged with the personal protection of President Chiang Kai-Shek and his family when they were staying in the area until it was abandoned in 1999.

The hall has recently been restored and as part of the ecomuseum provides a large space for rotating exhibitions in addition to others that tell of the history of the building.

Link: Daxi Martial Arts Hall

Daxi Sumo Arena (大溪相撲場)

When the Daxi Sumo Arena was completely reconstructed within Daxi Park, I was a bit surprised.

During the Japanese era, Kendo and Judo were taught within the Martial Arts Halls (like the one I mentioned just above), few people however realize that sumo was something that was also practiced here - although to what extent, I’m not particularly sure.

Nevertheless, since the reconstruction of the Sumo Arena, several events have been held by the local government to bridge the gap between Taiwan and Japan with regard to the sport of sumo. While I doubt we’re going to see a resurgence in the (somewhat obscure) sport here in Taiwan, it is a pretty cool nod to the past that surprises most people.

Daxi Police Chief Residence (大溪警察宿舍)

The former Daxi Police Chief’s Residence located behind the former Daxi Police Station (Currently Daxi Civil Centre) and as one of the highest ranking public officials in the area, the dorm that was provided for the chief and his family was considered quite swanky for the time.

Constructed in 1901 (明治34年), the dorm has remained occupied for much of its 120 year history, but has thankfully been restored and is now known as the Craft Exchange Hall (工藝交流館) and will feature exhibitions meant to help educate people on the process of making wood-art and connecting Daxi’s expertise to the world at large.

One of the best things about this dorm is that it comes equipped with a beautiful front and back yard and is covered with trees, making the whole thing more like a mansion than a dormitory. You’ll also find a bomb-shelter next to one of those trees, although it isn’t open to the public as of yet.

Daxi Police Dormitories (大溪警察宿舍)

Another one of the Police-related dormitories, the building we know today as the Artists Building (藝師館) was once a dorm for members of the Daxi District Police (大溪郡役所警察宿舍), which I’d venture to guess were a bit higher in rank than the town police. Constructed in 1941 (昭和16年), the dorm was one of the later additions to the group of dorms in the area, but is a beautiful single family dorm space and was likely occupied by a high ranking officer and their family rather than a group of officers.

Today the space is dedicated to Daxi’s masters of wood-art and tells their story.

Kensei Shoco Department Store (建成商行)

Currently undergoing a process of restoration, the facade of the former Kensei Shoco Department Store will likely be completely repaired within the next year or so. That being said, the interior of the building had already been completely demolished, leaving only the beautiful facade left standing. I’m not sure what they’ll ultimately do with the interior space, but the facade is probably the most beautiful and the grandest example of the art-deco baroque design that you’ll find in Daxi, so the fact that its being restored is a great thing.

Daxi Well (大溪百年古井)

The century-old Daxi well, located in an alley between the Martial Arts Hall and the Kensei Shoco Department Store is one of the only (still-functioning) wells of its kind around Taiwan and it has recently been given a bit of attention with a Japanese-style roof covering. Even though this is an important antique, it also serves as a functional one as the local people continue to pump water out of it today!

Daxi “Six-Row” Police Dorms (六連棟宿舍群)

The most recent of the former police dorms to graced with a restoration project, the so-called “Six Row” dorms are located in an alley to the rear of the former police station and are surrounded by the Police Chief Residence and the “Four Row” dorms, mentioned below.

Unlike those dorms, which were constructed for higher level members of the police force, this cluster of buildings were all relatively smaller, each of which only offering about 60㎡ of space (18坪) to their residents.

That’s about the size of a small two-bedroom apartment in Taiwan today.

When the colonial era ended, like all the other dorms, these smaller residences continued to be occupied by members of the police force, but as time passed they were renovated and changed quite a few times which altered their original layout and design.

As the dorms are currently still undergoing their restoration process, I’m not as of yet sure how they will be used within the larger ecomuseum, but my guess is that they will focus on the lives of the residents of the post-colonial era, similar to the exhibitions you’ll find at the nearby military villages that have been restored.

Daxi “Four Row” Police Dorms (四連棟宿舍群)

Currently used as an exhibition space dedicated to the ‘history’ of Daxi (大溪人。生活與歷史), I’d have to say that these dorms feature what is probably my favourite of all of the exhibitions put on display by the ecomuseum. Thanks to the meticulous focus on the history and development of Daxi during the colonial era and after, you’ll find informative displays within each of the buildings and if you’re as interested in this stuff as much as I am, its likely that you’ll be able to spend a considerable amount of time inside!

Daxi Agricultural Warehouse (大溪食鹽肥料倉庫)

Dating back to 1942 (昭和17年), the former Daxi Salt and Fertilizer warehouse is a distinctive building in that even though it was merely a warehouse, it featured some pretty distinctive architectural styles. Constructed only a few years prior to the end of the Second World War, the warehouse has served a number of roles in the years since, but is now open to the public as an exhibition and venue space.

With over 830 square meters of interior space, the warehouse will be an extension of the Wood-Art ecomuseum and will serve a number of roles, but one would hope that it would become popular music venue, like the spaces at Huashan in Taipei and the old warehouses in Hsinchu park, for example.

The building has only been freshly restored though, so we might need some time to see what they’ve got planned for it!

Daxi Tea Factory (大溪老茶廠)

Constructed in 1925 (大正14年) by the Taiwan Agriculture and Forestry Company (台灣農林公司), the Daxi Tea Factory was an important staging point in the production of tea during the Japanese era, especially since as I mentionnd earlier, Taoyuan was at one point responsible for the production of over 70% of Taiwan’s total tea export.

The tea factory is a short distance from downtown Daxi, and you’d probably need access to your own means of transportation to get there, but as one of the first Japanese era buildings in the Daxi area to be completely restored, it has long been a popular tourist destination and was for quite some time one of the most popular Instagram photo locations in Taiwan.

Getting There

If you weren’t already convinced, there is quite a lot to see and do while in Daxi, and if you are making plans to visit the historic village, you obviously have quite a few options. For most visitors, the obvious destination is the historic Old Street, but now that all of these Japanese-era buildings have opened up within the same area, we’re blessed with even more to do.

That being said you’ll also find popular tourist destinations like the Daxi Tea Factory, Zhai-Ming Monastery, the Cihu Mausoleum, the TUBA Church and the Sanmin Bat Cave nearby. Unfortunately some of these destinations are only only accessible if you have your own means of transportation.

So lets talk for a few minutes about how to get to Daxi Old Street.

A bit of a reminder though, I’ve introduced quite a few destinations in this article, so instead of giving directions to every single location, I’ll use a base starting point, the Daxi Civil Affairs Office (大溪區公所), where you’re conveniently able to make use of public transportation as well as finding parking for your cars or scooters.

Address: #11 Puji Road, Daxi District, Taoyuan City (桃園市大溪區普濟路11號)

GPS: 24.99368 / 121.29696

Car / Scooter

If you have access to your own means of transportation, getting to Daxi shouldn’t be too difficult. Simply input the address or the coordinates provided above into your GPS and you’ll find yourself there in no time. While driving a scooter shouldn’t pose much of a problem for most visitors, even during the busiest times, driving a car is a completely different story.

The problem with driving a car is that there are often traffic jams and long waits for parking spaces on weekends as well as during national holidays, when the area is at its busiest.

Given how narrow the streets are within the downtown core of Daxi, parking near the Old Street can be somewhat difficult and it is very rare that you’d be able to find roadside parking. This means that the further you park away from the main tourist area, the cheaper it will be.

In order to help control the flow of traffic, there are a number of parking lots in the area that you’ll want to consider, each of which I’ve marked on the map above. The first two are probably the best options for parking as they are the largest and cheapest of the parking lots, but they will require a bit of a walk to the tourist area.

Qiaotou Parking Lot 橋頭停車場 ($50NT)

Yuemei Parking Lot 月眉停車場 ($50NT)

Ting’er Parking Lot 停二停車場 ($30/hour weekdays - $40/hour weekends)

Old Street Park Parking Lot 老街公園停車場 ($30/hour weekdays - $50/hour weekends)

Old Street Parking Lot 老街停車場 ($30/hour weekdays - $50/hour weekends)

High Speed Rail / Train

As I’ve already mentioned, the construction of the railway forced the people of Daxi to come up with new ideas for making money - That being said, it should be fairly obvious that there aren’t any railway stations in the vicinity of the village. You can however take a train or the High Speed Rail and conveniently transfer to one of the buses or shuttles that take tourists out to the area.

High Speed Rail (臺灣高鐵)

Take the Taiwan High Speed Railway to Taoyuan HSR Station (桃園高鐵站) and from there transfer to Taiwan Trip Shuttle Bus #501

Taiwan Railway (臺灣鐵路)

From Taoyuan Railway Station (桃園火車站)

From the Taoyuan Train Station you’ll want to transfer to Taoyuan Bus #5096 to Daxi.

From Zhongli Railway Station (中壢火車站)

From the Zhongli Train Station you’ll want to transfer to Taoyuan Bus #5098 to Daxi.

Bus

There are a number of options for taking the bus to Daxi either directly from the railway stations in Taoyuan or from Taipei. I’ll provide each of the buses that you can take below with links to where you can find the bus, their route map and their schedule.

Taoyuan Bus #5096 (Taoyuan - Daxi)

Taoyuan Bus #5098 (Zhongli- Daxi)

Taoyuan Bus 9103 (Banqiao - Daxi)

Taoyuan Bus #710 (Yongning MRT Station - Daxi)

Taiwan Trip Bus #501 (Taoyuan HSR Station - Daxi) 台灣好行大溪快線

Links: Taoyuan Bus (桃園客運) | Taiwan Trip Shuttle (台灣好行)

Gallery / Flickr (High Res Photos)

References

探討大溪老街的建築特色與時代意義 (李政瑄, 邱筱雅, 楊佳穎)

桃園市立大溪木藝生態博物館 (Wiki)