One of my on-going projects over the past few years has been visiting and writing about Taiwan’s Martyrs Shrines, and if you’ve been reading this blog regularly, you’re likely aware that I’ve been doing so for a very specific reason. By now, it should be fairly obvious that when I visit these shrines, it doesn’t really have nothing to do with the purpose of the shrines, which are essentially propaganda tools of an authoritarian regime that has little to do with Taiwan.

My motivation for visiting is a little easier to understand and to put it simply, the majority of these so-called ‘Martyrs Shrines’ in Taiwan today were once the home of a Japanese-era Shinto Shrine, and whenever you visit one of them, you’re often able to find traces of that era of Taiwan’s history.

To be fair, even though the Martyrs Shrines were a tool used by the Chinese Nationalists, the same could be said about Shinto Shrines, and the Japanese regime that controlled Taiwan for over five decades. Both are pretty good examples of how a foreign power attempted to forcibly convert the citizens of Taiwan into their loyal subjects.

I just so happen to think Shinto Shrines are much more interesting - I’m sure not everyone feels the same way, and thats completely okay.

I’ve already written extensively about these Shinto Shrines-turned-Martyrs Shrines, so today I’ll be continuing by adding another piece to the puzzle with the Keelung Martyrs Shrine, which was once home to the former Keelung Shinto Shrine.

As is the case with most of Taiwan’s other former Shinto Shrines, the Keelung Martyrs Shrine continues to retain elements of the original shrine. Unfortunately there is very little information available online about either the Martyrs Shrine or the former Shinto Shrine, so taking into consideration that it was one of the earliest and most important Shinto Shrines in Taiwan, I’m going to delve pretty deep into describing its history below.

Hopefully this article helps people learn a bit more about the shrine.

Keelung Shinto Shrine (基隆神社 / きーるんじんじゃ)

I know, I’ve probably already made this claim several times already about other Shinto Shrines in Taiwan (but I really mean it this time), the Keelung Shinto Shrine was one of Taiwan’s prettiest shrines!

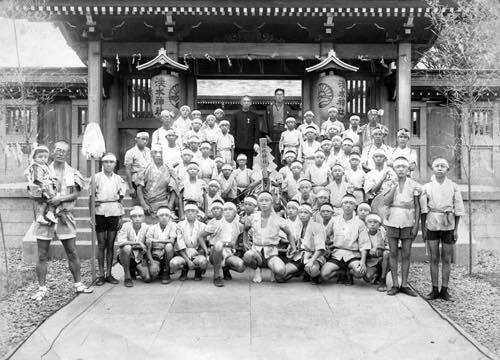

Dating back to 1912 (明治45年), the shrine was constructed as a branch of the Kotohira Shrine in southwestern Japan’s Kagawa prefecture (香川縣) - one of Japan’s most historic shrines, known for its patronage of the sea, ship transport and sailors.

Link: Kotohira-gu | 金刀比羅宮 (Wiki)

Originally named, “Keelung Kotohira Shrine” (基隆金刀比羅神社 / きーるんことひらぐう), that was changed three years later in 1915 (大正4年) to “Kiirun Jinjya” (きーるんじんじゃ), or the Keelung Shinto Shrine (基隆神社).

From the outset of the colonial era, Keelung, or “Kiirun” (きーるん) was one of the first areas in Taiwan where the Japanese set up official administrative agencies. This was in part due to the port, Taiwan’s northern-most, becoming instrumental in transporting people and supplies to the island, in addition to there already having an established, yet rudimentary railway link between the port and Taihoku (Taipei).

With that in mind, in the early years of the colonial era, there would have been a considerable number of Japanese nationals living in the area, (or stopping by while passing through) bringing with them their knowledge and expertise as well as their cultural and religious practices.

Prior to the construction of the Kotohira Shrine, a number of other Japanese religious buildings started to appear in the port area including the Jodo (淨土宗), Soto (曹洞宗) and Shingon (真言宗) Buddhist sects, in addition to a smaller Inari Shrine (稲荷神社).

Interestingly, even though Shintoism essentially disappeared when the Japanese left Taiwan, the Japanese Buddhist tradition took hold, and continues to shape the Buddhist experience in Taiwan today.

While there were a few small Shinto Shrines constructed in Keelung prior, none of them were large enough to take on the role of a ‘Guardian Shrine’ (產土神 / うぶすながみ), which meant that a larger shrine would have to be constructed in order to assist in maintaining a spiritual balance with all the development that was taking place around the port-city.

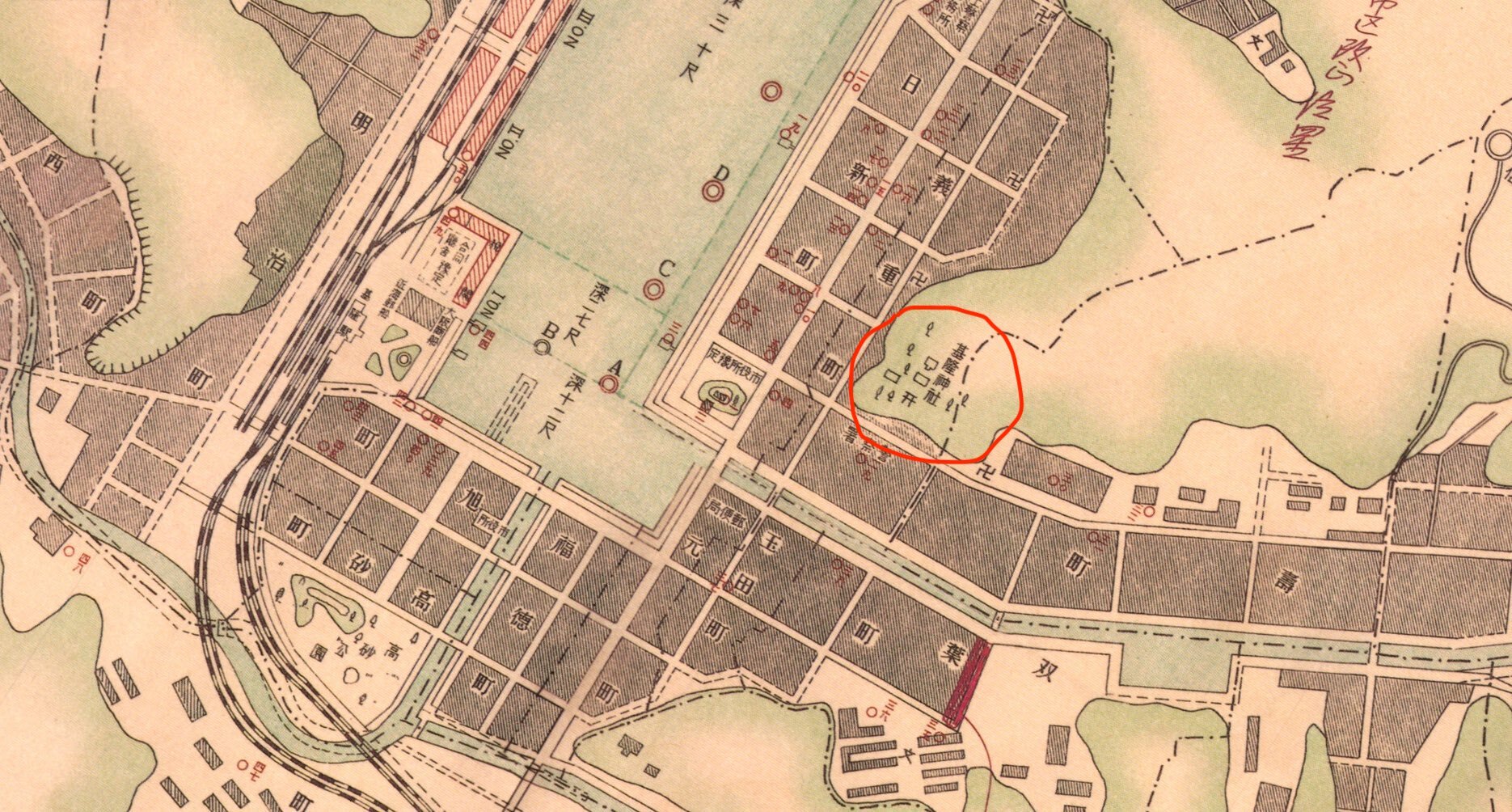

So, in 1903 (明治36年), a group of Japanese businessmen, and the technicians behind the construction of the Kiirun Power Plant (基隆發電所) initiated a campaign to raise funds for the construction of the shrine, which took until at least 1910 (明治43年).

Planning for the shrine however met with considerable difficulty as the location chosen for its construction was located on state-owned land and was reserved as part of the colonial government’s urban renewal plans (市區改正) for Keelung. The plan, which required mass land-expropriation sought to re-shape the city and modernize it by improving roads, electrifying the area, ensuring that there was proper sanitation and sewage and providing access to running water.

Similar urban renewal projects like this took place in every major city and town across the island, and are today still considered by many historians to be one of the most beneficial aspects of the period of Japanese rule, as these ambitious projects reshaped Taiwan’s towns and cities, improved quality of life, and were instrumental in Taiwan’s modern development. Today, the success of many of these development projects can still be felt across the country as many areas have maintained the original urban planning of the Japanese-era and expanded upon it.

Link: 臺灣日治時期都市計畫 (Wiki)

With the assistance of some powerful figures in the capital however, the application process to negotiate for the land was expedited within the Governor Generals office, but ultimately couldn’t be approved until the buildings that were previously constructed on the site were demolished, and the urban renewal was completed. In the meantime, fundraising and planning for the shrine continued and even though the application to build the shrine wasn’t ‘officially’ approved until 1911 (明治44年), the ceremonial ground-breaking ceremony was held a year prior.

It probably all sounds a bit confusing with the jumping back and forth, but there’s an important reason why they jumped the gun on the construction of the shrine before the application was formally approved.

This was because one of the founders of the shrine had to return to Japan to take part in a ceremonial ‘Bunrei’ (分靈) process in which a kami’s spirit is ‘divided’ and re-enshrined elsewhere. As mentioned above, the Keelung Shrine was originally meant to be a branch of the Kotohira Shrine, which means that they had to return to Kagawa Prefecture (香川縣) in Japan’s Shikoku Region (四國) to complete the process.

When the kami arrived in Taiwan in 1912 (大正元年), a ceremony was held to allow it to officially take up residence within the shrine, but by that time construction had only been partially completed with only part of the Visiting Path (參道) and the Main Hall (本殿) completed. This was due to the fact that even after several years of fundraising, the money raised for the construction of the shrine pretty much dried up, and was in competition with the various other fundraising campaigns taking place in the area - most notably for the construction of Kiirun Community Hall (基隆公會堂).

Likewise, as mentioned above, one of the original reasons for the construction of the shrine was to build a “Guardian Shrine” for the port city, but as it was initially constructed as a branch shrine, it couldn’t serve the same purpose as a typical Prefectural Level Shrine due to the rigid set of rules that governs Japanese Shinto Shrines.

This is especially the case as the enshrined deity, Ōmononushi (大物主命), the same deity enshrined at the Kotohira Shrine back in Japan wasn’t the major type of kami that you’d expect at a shrine of that rank, and it was likely that only people from that area of Japan would contribute financially.

To solve this problem, it was decided to change the name of the shrine to the “Kiirun Jinjya” (きーるんじんじゃ), or the “Keelung Shinto Shrine” (基隆神社) in 1913 (大正1年) in order to gain more support, and donations from local residents. As fundraising efforts continued, the Hall of Worship (拜殿) was completed that same year and a longer list of kami took up residence inside, including Amaterasu, the Three Deities of Cultivation, Emperor Sutoku, and Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa.

Unfortunately as construction on the shrine continued, disaster struck in 1914 (大正3年) when a typhoon blew through the area and destroyed parts of the shrine, forcing an expensive reparation and rebuild project that took place as the other parts of the shrine were still being built.

Given all of issues with fundraising, bureaucratic complications and typhoon damage, I guess it shouldn’t really surprise anyone that it took more than a decade to complete construction on the Keelung Shrine and have it fully opened to the public.

Located on a steep hillside on the east-side of the port, the shrine faces in the opposite direction of the ocean and even though purchasing the land proved to be difficult, it was essentially what you’d consider the ideal location for a shrine of this nature. It was not only close to the port, but the commercial and residential areas of the city as well, it was easy to access, and more importantly was also in an area surrounded by the natural environment.

If you weren’t already aware, Shinto Shrines are renowned for their impressive ability to blend in harmoniously with the natural environment around them, which shouldn’t really be all that surprising considering that it is a religion that worships deities related to nature. Similarity, the Shinto deities, or “kami” are almost always objects found in the natural environment such as animals, birds, rivers, mountains, trees, etc.

For the Shinto, the relationship with the natural environment is extremely important given that the earth can bring both blessing and disaster. It is thought that if the kami are worshipped adequately and in a responsible way, then they will bring good fortune to the world. If on the other hand they are disrespected or neglected, they will react violently or bring misfortune. Essentially, respect for the environment is one of the main tenets of Shintoism and the construction of these shrines never fails to keep that in mind. With over 80,000 shrines in Japan, Shintoism contributes to society providing ecological sanctuaries that can be enjoyed by all.

Before I talk about what you would have found at the Shrine while it was still around, lets take a few minutes to talk about the deities enshrined within:

Amaterasu (天照皇大神)

One of the children of the god and goddess of creation, Izanami (伊邪那美命) and Izanagi (伊邪那岐神), Amaterasu is one Shintoism’s most important deities.

Known more formally as Amaterasu-Ōmikami (天照大御神), she is the goddess of the sun and the universe, and is considered to be the mythical ancestor of the Imperial House of Japan.

Enshrined at the Ise Grand Shrine (伊勢神宮) in Ise, Mie Prefecture (三重縣), worship of the goddess is often directly linked to worship of “Japan” itself, known as “Japanese Spirit”, or Yamato-damashii (大和魂).

This in itself was problematic during the period when State Shintoism was one of the tools used to fuel the militarism of the era, but worship of Amaterasu far predates all of that insanity as she has been one of the most important Shinto deities for more than thirteen centuries.

Given that most Shinto Shrines in Taiwan would have been home to an Amaterasu shrine, this was one of the reasons why the Chinese Nationalists were so keen on destroying the shrines, given her links to the militarism of the early 20th Century.

The Three Deities Of Cultivation (かいたくさんじん / 開拓三神)

The “Three Deities of Cultivation”, consist of three figures known for their skills with regard to nation-building, farming, business and medicine.

The three “Kaitaku Sannin” are as follows:

Ōkunitama no Mikoto (大國魂大神 / おおくにたまのかみ)

Ōkuninushi no Mikoto (大名牟遲大神 / おおなむちのかみ)

Sukunabikona no Mikoto (少彥名大神 / すくなひこなのかみ)

While these deities are also quite common within Japan’s Shinto Shrines, they were especially important here in Taiwan due to what they represented. Given Taiwan’s position as a new addition to the Japanese empire, ‘nation-building’ and the association of a ‘Japanese way of life’ was something that was being pushed on the local people in more ways than one. Likewise, considering the economy at the time was largely agricultural-based, it was important that the gods enshrined reflected that aspect of life.

Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa (北白川宮能久親王)

Prince Yoshihisa, a western educated Major-General in the Japanese imperial army was commissioned to participate in the invasion of Taiwan after the island was ceded to the empire.

Unfortunately for the Prince, he contracted malaria and died in either modern day Hsinchu or Tainan (where he died is disputed), making him the first member of the Japanese royal family to pass away outside of Japan in more than nine hundred years.

Shortly after his death he was elevated to the status of a ‘kami’ under state Shinto and was given the name “Kitashirakawa no Miya Yoshihisa-shinno no Mikoto“, and subsequently became one of the most important patron deities here in Taiwan, as well as being enshrined at the Yasukuni Shrine (靖國神社) in Tokyo.

Link: Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa (Wiki)

Coincidentally, sharing part of the same mountain as the former Keelung Shinto Shrine, you can find a monument that was erected in memorial for the Prince Yoshihisa. The monument isn’t really all that well advertised, but it wasn’t (completely) destroyed when the Chinese Nationalists took control of Taiwan. It was however completely defaced and the Chinese characters that were written on the front of the monument have been filled in with cement.

That being said, the monument is another one of Keelung’s many Japanese-era structures that continue to exist and if you’re interested you should definitely take some time to visit.

Japanese Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa Monument (北白川宮能久親王紀念碑)

Address: #68, Alley #122 Zhongchuan Road, Keelung City (基隆市中正區中船路112巷68號)

Emperor Sutoku (崇德天皇)

The inclusion of Emperor Sutoku as one of the kami enshrined at the Keelung Shrine was certainly an interesting and somewhat obscure choice, given his role as one of the Three Great Onryo of Japan (日本三大怨霊).

Emperor Sutoku (崇徳天皇/すとくてんのう) was the 75th Emperor of Japan, reigning from 1123 to 1142 during the Tenji (天治), Daiji (大治), Tensho (天承), Chosho (長承), Hoen (保延) and Eiji (永治) Periods.

Although his reign as Emperor spanned a period of nineteen years, his time in power was considerably shorter given that he officially came to the throne at the age of three - This left the country governed under the stewardship of his father, Emperor Toba (鳥羽天皇), until Sutoku came of age.

It’s unclear when that actually happened, but the Eiji era (1141 - 1142) when the Emperor was 22 years old would become the most eventful, and final years of his reign.

Considered a “bastard”, Sutoku was not well-liked by his “father”, Emperor Toba, who was forced to abdicate the throne when Sutoku was just three years old. Unfortunately for Sutoku, his true father, former Emperor Shirikawa (白河天皇) died in 1129 leaving Toba with a firm grip on the reigns of power.

The story of Emperor Sutoku is ultimately a sad tale that involves a life of alienation, emotional abuse and coercion resulting in his being forced to adopt Toba’s bastard son (in a situation similar to his own), early retirement, a failed attempt at retaking the throne and banishment to a distant province to live his life as a monk.

Sutoku passed away in 1164 having lived his final years as a monk, but after being disposed and humiliated, it is said that he was full of bitterness and rage. Prior to his death, legend has it that he bit off his own tongue and wrote holy manuscripts with his own blood, which he then sent back to Kyoto, imbuing them with his hatred for the imperial court.

But by that time he was already persona-non-grata and was largely ignored.

When he passed away, a series of strange events occurred, with storms, plagues, fires, droughts and earthquakes all taking place in the capital and resulted in a civil war that ended the dynasty.

This is how Sutoku became known as one of the “Nihon San Dai Onryo”, or the “Three Great Demons of Japan,” along with Sugawara no Michizane (菅原道真) and Taira no Masakado (平将門).

According to Japanese folklore, an “onryo” (怨霊) is a kind of “yokai” (妖怪),or a demon that is considered to be a wrathful or vengeful spirit capable of causing harm to the world in an attempt to exact revenge against their enemies. This isn’t something that people in Japan really joke about, and as recent as 2012, Sutoku was blamed for an earthquake that took place in the Kanto region after an NHK drama depicted his transformation into a demon.

Links: The Peculiar Life of Emperor Sutoku (Yabai) | Sutoku Tenno (Yokai)

So why was Emperor Sutoku enshrined at the Keelung Shinto Shrine?

Well, in 1868 (明治元年), the first year of Emperor Meiji’s reign, it was commanded that Sutoku be enshrined as a kami at the Shiramine Shrine (白峯神宮) in Kyoto, which was seen as his return to the capital and an attempt to sooth the country’s most vengeful sprit.

Shintoism is a complicated polytheistic religion with a myriad of deities hailing from both natural and supernatural world. Given that there are so many deities, it shouldn’t surprise anyone that there are those that are ‘good’ and those that are ‘bad’ in an attempt to better explain how the world works.

Kami are generally divided by their “mitama” (魂), or their ‘spirits’ into “Nigi-mitama” (和魂 / にきたま) and “Ara-mitama” (荒魂 / あらたま), essentially positive and negative. In the latter case, the “nigi-mitama” are often blamed for natural disasters, droughts, food shortages, war and suffering. So, in order to avoid misfortune, it is important to deal with any negative energy through pacification rites and worship.

This is why Emperor Meiji brought the remains of former Emperor Sutoku back to Kyoto and placed them within a shrine dedicated in his honor. Given the centuries of havoc brought on by the rage and bitterness of Sutoku, it was thought that bringing him back to the capital to give him the proper burial rites of an emperor would help to ease his path into becoming an honourable spirit.

Okay, so once again lets get back to the Keelung Shinto Shrine.

Why would they enshrine one of Japan’s most vengeful spirits within the important port city?

If that isn’t clear already, the pacification of these negative spirits is an important ritual for maintaining the safety and security of society. The inclusion of Emperor Sutoku within the Keelung Shrine was an attempt to ensure the safety of the port, which would have been one of the busiest in Taiwan at the time. It was especially important at the time because Emperor Meiji had only started the pacification process of the negative spirit a few decades prior to the construction of the shrine, and if more people worshipped him, less terrible things would happen.

Ōmononushi (大物主命)

Similar to the Three Deities of Cultivation mentioned above, Ōmononushi-no-kami (おほものぬし) is another one of Shintoism’s most important deities. Known literally as the ‘Great Thing Master’ or the ‘Great Spirit Master’, he is likewise considered the god of nation-building, agriculture, business, medicine and brewing.

More importantly in this case however, Omononushi is known as a patron spirit for seafarers.

Dating as far back as the ‘pacification’ and development of the earth, the mythology of Omononushi was told as far back as 712CE in the Kojiki (古事記), but you’ll also find mention of him in other important books like the Shoki (日本書紀) and the Fudoki (風土記).

So, even though he serves the same purpose as the gods mentioned above, his importance and power in the scope of Shintoism far exceeds them.

Link: Ōmononushi (Wiki)

Architectural Design

The Keelung Shrine was constructed on a steep hillside and was beautifully layered with the traditional “Visiting Path” rising up not just one steep set of stairs, but two, culminating with the ‘Main Hall’ located on a third layer to the rear of the Hall of Worship.

With this in mind, you’ll have to take into consideration how much effort it took to shape the land into the various layers for the construction of the shrine, as well as the genius it took to construct a drainage system that would allow rainwater from the mountain above to flow down the mountain, without causing any structural damage to the shrine.

As the largest shrine in the Keelung area, the shrine would have featured all the bells and whistles of a typical Prefectural Level Shrine (縣社) and consisted of the following:

A Visiting Path or “sando” (參道 /さんどう)

Stone Lanterns or “toro” (石燈籠/しゃむしょ)

Stone Guardian Lion-Dogs or “komainu” (狛犬/こまいぬ)

Shrine Gates or “torii” (鳥居 /とりい)

A Sacred Fence or “tamagaki” (玉垣 / たまがき)

An Administration Office or “shamusho” (社務所/しゃむしょ) 50坪

A Purification Fountain or “chozuya” (手水舍 /ちょうずや) 1.5坪

A ‘Mikoshi Storehouse’ or “shinyosha” (神輿舎 / しんよしゃ) 3坪

A Hall of Worship or “haiden” (拜殿 /はいでん) 300坪

An Offertory Hall or “heiden” (幣殿 / へいでん)

A Main Hall or “honden” (本殿/ほんでん) 110坪

A massive cannon (戰利砲)

What we know about the architectural design of the shrine today comes from a combination of the layout that remains today, and the assistance of historic photos and records.

Starting with the ‘Visiting Path’ (參道), there was a large Shrine Gate (一の鳥居) on ground level. You’ll still find a shrine gate in the same spot today, but it has since been converted into a Chinese-style gate. Once you passed through the gate you’d be met with two large stone-guardian lion-dogs (狛犬) standing on pedestals on either side. The stairs that led up the hill to the shrine were laid with concrete and both sides featured stone lanterns (石燈籠) that were set up on pedestals.

Once you reached the top of the first set of stairs, you’d find a second Shrine Gate (二の鳥居), and then an open space where there was an Administration Office (社務所) and a Purification Fountain (水手舍) on its right.

And (from the 1930s on), a giant twenty-eight ton cannon on its left.

The path would have continued to the right of the Administration Office where you’d reach a third Shrine Gate (三の鳥居), with two giant stone lanterns, and a much wider set of stairs that led to the second level. When you reached the top of this set of stairs you would have found the final Shrine Gate (四の鳥居), and two smaller Stone Guardian Lion-Dogs (狛犬) on the left and right side - both of which still exist today.

Often appearing as a male and female, the ‘komainu’ are only distinguishable only by their facial expressions, with the male “a-gyo” (阿型) having an open mouth and the female “un-gyo” (吽形) having a closed mouth. The male guardian is located on the left and the female on the right. If you look closely on their pedestals on the bottom you’ll discover that they date back to 1917 (大正8年), and the names of the people who donated them to the shrine. The fact that both of them continue to exist today in itself is somewhat of a miracle.

Link: Komainu Lion Dogs (Japan Visitor)

Once you pass through the shrine gate you would have been met directly with the beautiful ‘Hall of Worship’, otherwise known as the ‘oratory’ or the “haiden” (拜殿). The hall was constructed in an architectural style reminiscent of the Maidono Hall (舞殿) at the nearly 1400 year old Yasaka Shrine (八坂神社 / やさかじんじゃ) in Kyoto.

Link: Yasaka Shrine (Japan Guide)

Elevated off of the ground on a concrete base, the architectural style of this Hall of Worship allowed it to stand apart from many of the other shrines around Taiwan in that it was an open-air building designed in the seihoukei haiden (正方形拝殿) style. Held up with a network of pillars around the perimeter of the building, it featured a beautiful Irimoya-zukuri (入母屋造) hip-and-gable roof and given that it was an open-air building, it featured an enclosed Offertory Hall or “Heiden” (幣殿) connected via a passageway at the rear.

<PHOTO>

Based on historic photos of the shrine, it appears that the overall design of the hall was likely constructed using the “ishinoma-zukuri” (石の間造) style that allowed both the Haiden and the Heiden to be connected by a passageway known as “ishi-no-ma” (石の間). This would have been an instrumental design feature that allowed the main building to maintain its open-air design as well as distributing the weight of the massive roof with the help of the network of pillars.

It was also pretty important for the elaborate shape of both of the roofs as the larger roof on the front part of the building featured the ‘four-sided’ Irimoya hip-and-gable roof, while the smaller Heiden building to the rear featured a two sided kirizuma nagare-zukuri (切妻流造) gable-style roof, creating a three-dimensional flowing design.

One of the interesting things about the old photos of the shrine were the purple curtain/banners (御神幕) that surrounded the open-air sections of the Hall of Worship. Each section featured a crest that was used to represent Taiwan’s Shinto Shrines (臺灣神社徽) consisting of a combination of the Taiwan Crest (台字徽 / たいわん) and the fourteen-petal chrysanthemum flower, known as the kikumon (菊紋).

<PHOTO>

For a look at some of the absolutely beautifully designed crests used in Taiwan during the colonial era, check out the website linked below which features descriptions for quite a few of them.

Link: 日治臺灣主要都市市徽一覧

Finally, to the rear of the Hall of Worship, there was another steep set of stairs that led directly to the Main Hall or the “Honden” (本殿), which was off-limits to the public. Elevated above the rest of the shrine, the Hall of Worship was where the deities were enshrined and would have only been accessible to the priests who lived and worked at the shrine.

The small building featured a beautiful kirizuma-zukuri roof (切妻造), which is best described as a roof that looks like ‘an open book placed with its face down, or like the Chinese character “rù” (入).

<PHOTO>

In 1934 (昭和9年), the Keelung Shinto Shrine was updated into a Prefectural Level Shrine (縣社) under the Governor General’s Office policy to ensure that there was a shrine in every borough, town and city in Taiwan (一街一庄一神社). As mentioned above, as part of the celebrations for its upgrade in status, the shrine was gifted a giant cannon.

When the Colonial Era ended in 1945 (昭和20年), the Keelung Shinto Shrine, like many of the other larger Prefectural Level Shrines was converted into a Martyrs Shrine (忠烈祠) by the Chinese Nationalist Government.

The cannon was then moved to a park further up the mountain and parts of the shrine started to change. Ultimately the vast majority of the shrine was torn down in 1969 (民國58年), and a Chinese-style shrine was constructed in its place.

The Keelung Martyrs Shrine (基隆忠烈祠)

After that long-winded deep dive above about a Shinto Shrine that doesn’t even exist anymore, it would be understandable if you’ve read this far and you’re asking yourself:

“What exactly is a Martyrs Shrine?”

That’s okay - I’ve visited quite a few of these shrines and I still find myself asking this question.

To put it in simple terms, Martyrs Shrines in Taiwan are more or less war memorials for the fallen members of the Republic of China Armed Forces.

There are over twenty of these shrines throughout Taiwan (including the outlying islands), each of which with has interesting history, but is a history that doesn’t necessarily ever relate to anything to do with the Martyrs Shrine itself.

Its also important to note that these shrines actually have very little to do with “Taiwan” as the majority of the ‘martyrs’ worshipped in the shrines were soldiers who died during the various conflicts in China from the founding of the Republic of China in 1912 until the 1950s.

That being said, even though the ‘Republic of China’ has been at peace for several decades, if a member of any branch of the Armed Forces passes away in the line of duty, they are also afforded the respect of becoming a martyr.

If you’d like more detail about these shrines, I recommend taking a few minutes to check out my post about the National Revolutionary Martyrs Shrine, which explains the purpose of these shrines.

I suppose the key thing to understand about Taiwan’s ‘Martyrs Shrines’ is that of the twenty or so that exist in the country today, the vast majority of them are located on the site of a former Shinto Shrine.

Some of which still retain bits and pieces of their original design and layout, but have been altered to reflect their new roles while others have been completely torn down and rebuilt. The Keelung Martyrs Shrine is no different as it is located on the site of the former Keelung Shinto Shrine, and even though most of what once stood on this site has been torn down, it continues to retain much of its original layout with a few little surprises here and there.

As I’ve already done several in the past with these articles about Taiwan’s Martyrs Shrines, I’ll explain the current shrine by following the path of the original Shinto Shrine so that you can better understand what currently exists on the site and what used to be there.

Before we get into that though, let me first explain the short history of the shrine.

When the Second World War ended with the Japanese Empire’s surrender to the Allied Forces, one of the conditions of their defeat was that they had to relinquish control of the areas they conquered in the decades leading up to the war. This included areas in Korea, Manchuria, China and Taiwan, among others. Having to surrender control of these areas was certainly a major blow to Japan, but none of them could have ever compared to the loss of Taiwan, which was Japan’s most treasured colony.

Control of Taiwan was ambiguously awarded to the Republic of China and when the Chinese Nationalists arrived here, they were gifted with an island that was developed far better than that of the rest of China. That being said, they inherited a population of people who resisted their rule and who (for the most part) considered themselves Japanese citizens, or had no interest in being ruled by another foreign power. This resulted in protests, massacres and what would become known as the period of White Terror (白色恐怖), where the island was ruled with an iron fist for decades.

Link: White Terror | 白色恐怖 (Wiki)

Back in China, Chiang Kai-Shek and his Chinese Nationalists found themselves on the losing end of the Chinese Civil War, which eventually forced him to relocate the government to Taipei, bringing with him millions of people and a large portion of China’s priceless national treasures.

Even though Taiwan was pretty well-developed at the time, the sudden influx of more than two million Chinese refugees put a major strain on the island’s infrastructure, in addition to putting the refugees at odds with the local population.

The Chinese Nationalists having suffered through a terrible war against the Japanese back at home during the Second World War, figured it was better to simply get rid of any Japanese cultural symbols in order to ensure a quicker transition to Chinese Nationalist rule.

This meant that the majority of Taiwan’s more than two hundred Shinto Shrines would have to be demolished. That being said, many of the larger Prefectural Level Shrines were a little too nice to be simply torn down, so a few of them were saved from being torn down by being converted into Martyrs Shrines, which replaced one regimes cultural symbol with a culture symbol of another regime.

The Keelung Shinto Shrine was one of the lucky Shinto Shrines that was able to escape wanton destruction and for more than two decades only a few minor details were changed to better reflect the change in regime.

In the late 1960s however, the international political situation started to shift and countries started to formally recognize the People’s Republic of China, which had shut its borders to most of the world after 1949 to better facilitate their ‘Communist’ revolution. One of China’s pre-conditions for the establishment of formal ties was that countries had to respect its position on the situation regarding Taiwan.

With a sudden loss of its seat in the United Nations and international relations in tatters, the government of the Republic of China in Taiwan acted immaturely in its response and burned quite a few bridges in the process. When the Japanese government signed their own Joint Communiqué with the PRC in 1972, the government here in Taiwan responded by tearing down even more of the island’s Japanese past, which included many of the remaining Shinto Shrines.

The Keelung Shinto Shrine ended up being one of the shrines that got demolished, and in 1969 (民國58年) construction started on a replica of a Northern-Chinese Palace style (中國北方宮殿樣式) designed replacement.

That being said, the construction process was pretty half-assed and even though the main shrine was completed in 1972, much of the site remains to this day a ‘work in progress’ and has suffered through long periods of neglect.

Suffice to say, annual numbers place the number of people who visited the Shinto Shrine in 1933 at more than 83,000 people. Given how so few people actually visit the shrine these days, it would be hard to imagine that more than 83,000 people have visited since 1972.

Shrine Gates (鳥居 / 牌樓)

Once home to four Japanese Shrine Gates, otherwise known as “Torii”, the Martyrs Shrine currently features two beautiful Chinese-style “Pailou Gates” (牌樓) on street level, and just as you reach the Martyrs Shrine.

While the street-level gate acts as a gate to the Martyrs Shrine, it is officially the pedestrian entrance to Zhongzheng Park (中正公園), which takes you up the path to the shrine and beyond to the beautiful trails on the mountain park that overlooks the port.

The gate has a beautifully decorated red ‘roof’ with two multi-coloured ridges below, and is easily 20 meters high, making it a very noticeable while walking down the street.

The second gate further up the path is the official Martyrs Shrine Gate (忠烈祠牌樓), and following tradition includes three passageways, a multi-layered roof, and plaques with Chinese calligraphy on both the front and back. Strangely, gates of this kind at other Martyrs Shrines around Taiwan feature similar plaques, with a number of ‘revolutionary’ phases, but they it seems like they were a bit lazy with this one as the three plaques on the front and back are exactly the same.

On both sides you’ll find the largest plaque in the centre that reads “Martyrs’ Shrine” (忠烈祠) with the words “成仁” (chéng rén) and “取義“ (qǔ yì) above the left and right archway, which translate as ‘to die for a good cause’ and ‘to choose honour over life’ respectively.

Visiting Path (參道)

The Visiting Path to the Martyrs Shrine is one of the pieces of the Shinto Shrine that was never really affected, like the rest of the shrine. The original path retains much of its century-old elements and if you’ve ever visited a Shinto Shrine in Japan, it should be easily identifiable.

Starting from ground-level, the path to the shrine is a two-sided stone set of stairs with a railing in the middle and pedestals on both sides. The pedestals were once home to shrine’s Stone Lanterns, but they’ve all since been removed or destroyed. Once you reach the top of the first set of stairs you’ll discover an open section of land where the Shinto Shrine’s Administration Building once existed.

From there, the stone path continues to the right where you’ll reach a second set of steep stairs where you’ll see the second Shrine Gate at the top. Near the base of the stairs you should take a look at the base of the green hill where you’ll see the reinforced cement base that was constructed along with the Shinto Shrine to prevent landslides and help with water drainage.

When you reach the top of the second set of stairs, you’ll find a set of the original Stone Lion-Dog Guardians on both the left and right side, both of which have amazingly survived since they were gifted to the Shinto Shrine in 1918 (大正8年).

Hall of Worship / Martyrs Shrine (拜殿 / 忠烈祠)

Interestingly, the current Main Hall of the Martyrs Shrine building was constructed on the exact location of the original Shinto Shrine, and continues to use the original base to elevate it off of the ground that was constructed for the Shinto Shrine almost a century ago.

The architectural design of the building however has changed considerably.

Constructed in the Northern-Chinese Palace style, the shrine follows a similar architectural design as many of the other Martyrs Shrines around Taiwan in that it has beautiful red pillars around the perimeter of the building that help to hold up an elaborate two-layered roof.

Between the first and second layer of the roof you’ll find a horizontal plaque in the centre that reads “zhōng liè cí” (忠烈祠), or “Martyrs Shrine” and below that you’ll find another that reads “zhōng liè qiān qiū” (忠烈千秋), which is translated literally as “The Loyalty of the Martyrs.”

On the apex of the roof you’ll find the circular star of the Republic of China, one of the iconic images of the Chinese Nationalist Party. The blue and white star hasn’t really aged well though, and is both fading and falling apart, much like the Chinese Nationalists themselves.

I can’t really tell you much about the interior of the building as like many of the other Martyrs Shrines around the country, its not open to the public very often.

The thing about these shrines is that they’re not the same as the typical temples or shrines that you’ll find all around Taiwan, and it is actually very uncommon for people to just randomly show up to pray.

The Martyrs Shrines serve their purpose as war memorials (and propaganda tools) for the former authoritarian regime, which is why you’ll rarely find many visitors.

Main Hall / Martyrs Hall (本殿 / 烈士堂)

The last section of the Martyrs Shrine is somewhat of a recent addition, but is located in the beautiful space where the Shinto Shrine’s Main Hall (本殿) was once located.

When the Shinto Shrine was torn down and the Martyrs Shrine was constructed in its place, the area that was once home to the Main Hall became home to a shrine to the glorious dictator, President Chiang Kai-Shek. Unfortunately, statues of the murderous authoritarian don’t seem to be very popular in Taiwan these days and they have a hard time keeping their heads attached to their neck.

The statue of CKS ended up being defaced so many times over the years that the people in charge of the shrine just removed it entirely and replaced it with a “Martyrs Hall”, something that the vast majority of people who visit the area tend to miss.

Given that I know quite a bit about the architecture of Shinto Shrines, it was always obvious that if I walked around to the rear of the Martyrs Shrine that there would be a path to where the Main Hall would have been located.

In this case, the path to the Main Hall, an extension of the “Visiting Path” mentioned above would have been off-limits to the public, while the Shinto Shrine was still in existence, but today is pretty much open to anyone who wants to check it out.

This path though, is absolutely beautiful.

Constructed with cement, the path is yet another steep set of stairs that bring you up above the roof of the Martyrs Shrine below. The entire area is tree-covered and is harmonious with nature, just like a Shinto Shrine should be.

The path was so beautiful that I made sure to take a rare photo of myself walking up it!

When you get to the top of the path you will notice a large open space on the mountain where they’ve now constructed a small, but beautiful “Martyrs Hall” (忠烈堂), which like the shrine below is pretty much always closed to the public.

In front of the hall you’ll find two trees that were planted on either side of the building and date back to the Japanese era. The trees have had over a century to grow and now they’re pretty large and help to add to the natural surroundings of the area.

If you visit the Martyrs Shrine, I can’t recommend enough that you walk around to the rear of the building to check out this area as I find that its probably the most important and was once the most sacred area of the shrine.

Getting There

Address: #278 Xin-er Road. Zhongzheng District, Keelung City (基隆市中正區信二路278號)

GPS: 25.131410 121.745610

Keelung, unfortunately isn’t the easiest city to get around, especially if you’re new to the city and aren’t really familiar with the public transportation. That being said, most of the popular tourist attractions are conveniently located within the downtown core of the city meaning that if you visit, you can easily access most of what you’ll want to see on foot.

Adding to the difficulty in getting around, Keelung doesn’t currently have access to YouBikes, GoShare, iRent, or Wemo, which means that if you prefer to get around on bike or scooter, you’ll have to rent one from one of the rental shops near the train station, which is much more expensive than those services listed above.

Similarly, if you have access to a car, I don’t really recommend driving it around Keelung as the city is cramped and parking can quickly become an issue, especially with all the one-way streets and the traffic congestion.

If you plan on visiting the city, I recommend simply taking the train and walking around.

You can reach most of what you’ll want to see within 10-20 minutes of walking, which is considerably shorter than the time it will take you to find parking and walking to wherever you want to go from there!

The Keelung Martyrs Shrine is a short walk from the railway station and is just across the bridge from the popular Miaokou night market (廟口夜市). As mentioned above, the Martyrs Shrine is located on the base of a mountain, which features quite a few temples and tourists attractions, so a visit to the shrine should probably also include the short walk to the peak where you’ll be able to enjoy some really amazing views of the Keelung cityscape.

If you follow my advice and walk, getting to the Martyrs Shrine is rather straightforward - Walk straight down Zhongyi Road (中一路) until you reach Aisi Road (愛四路) where you’ll turn left and cross the Japanese-era Jinji Bridge (基隆十二生肖橋). From there, continue walking straight until you reach Xin-er Road (信二路) where you’ll find the gate to the Martyrs Shrine on the right, directly across from a large fire station.

While you’re in the area, it should go without saying that you should check out the night market, but don’t forget to visit Zhongzheng Park (中正公園), which is a short walk up the mountain from the Martyrs Shrine, in addition to the Maritime Plaza (海洋廣場) and some of the other tourist spots in the area.

A visit to the Martyrs Shrine certainly won’t take that much time out of your day, but given that this is a spot that has played a pretty big role in the development of the city, its probably worth a bit of your time before you move on to your next destination!

References

臺灣神社表 (Wiki)

臺灣日治時期都市計畫 (Wiki)

忠烈祠 (基隆舊夢綠都心中正公園)

忠烈祠 - 基隆神社遺跡 (Tony的自然人文旅遊)

日治時期基隆神社的興建與昇格之研究 (陳凱雯)

歷史之鏡 基隆忠烈祠,走訪台灣史蹟 (微笑台灣)

基隆忠烈祠:日本人走後 神社去了哪裡?(雨都漫步)

History of the Keelung Martyr’s Shrine (Keelung for a Walk)

兩個時代的傳承 -忠烈祠與神社 (ARCGIS)

日治時期臺灣各級神社的選址與社域的空間特性 (陳鸞鳳)