I can be a patient person, but in some cases, enough is enough.

I’ve had a skeleton of a post about the Erlin Martial Arts Hall in Changhua sitting in my blog queue since 2017, waiting to be published. With little more than a dozen of these historic buildings remaining in Taiwan today, I figured that I’d hold off on publishing anything about this one until it was fully restored and reopened to the public.

My patience though, has sadly worn quite thin.

It got to the point that I thought if I keep waiting for Changhua County to get its act together, I’d likely be a senior citizen by the time they actually get around to restoring this building.

When I originally wrote an article about this Martial Arts Hall more than six years ago, I was still quite new to this whole blogging thing, and was likewise still new to my exploration of Taiwan’s historic buildings from the Japanese era. So, if I compare what I originally wrote years back to what I’m publishing today, it’s not even close.

This article should prove to be a much more well-rounded one that benefits from my years of experience and research on the topic.

That being said, while all of the text has been completely updated, I’m sad to say that the photos I’m sharing right now are the going to be the same as those I had prepared five years ago due to the fact that myself, nor anyone else has really been able to get many photos of the building in recent years.

Essentially, I’m publishing this article today to simply have the information in place for (what I sincerely hope) what will eventually become an updated version, which will be complete with photos of the fully restored building.

Until that happens, I’ll make use of some of the blue prints and designs of the building that have been published by the Changhua County Government to better illustrate some of the things I’m talking about. The work they have done researching the building and it’s architectural design is incredible, and without it, we would know very little about the building, so cheers to them for that!

For those of you who have been following my writing for a while, especially with regard to my Urban Exploration-related work, barriers don’t usually prevent me from getting the photos I need - Sadly though, in the case of this Martial Arts Hall, several factors that have combined to ensure that people like me aren’t snooping around. The most obvious is that building is completely locked up and a barrier has been erected around its perimeter to prevent anyone from getting too close to the historic building.

The other reason is that it is located next door to the Erlin Police Station, which has cameras watching the grounds. So, even though I found a way of getting around the barrier, I wasn't about to go snooping around while the police would be able to see me in plain sight from the police precinct.

So what exactly is the problem with the Erlin Martial Arts Hall and why have we had to wait for so long for it to get fixed up? Well, that’s a bit of a complicated issue, but I’ll do my best to explain it as briefly as possible.

To keep things simple, it’s all about money. Isn’t it always, though?

However, that’s a bit of a simplistic argument as to what’s going on here. As I mentioned earlier, the situation is a lot more complicated than that, and there is an ample amount of blame to be thrown around.

It would be easy to focus our indignation at the Changhua County Government, which as one of the nation’s most cash-strapped municipalities, has had trouble coming up with funding for the restoration of the heritage buildings within its borders - With so little cash to throw around, the county tends to spend it restoring buildings in the coastal town of Lugang (鹿港), one of the areas’s most popular tourist attractions - Obviously hoping that there will be a trickle-down effect that will help bring tourist dollars into the county.

The focus on Lugang obviously has been of great benefit to the people of Lugang, and its tourism sector, but the other townships within the county have more or less been left behind.

The blame here though cannot be placed solely on the local government as there are land ownership issues taking place here that have complicated the matter. Currently there are six land owners, who, in addition to the government own pieces of the land where the Martial Arts Hall is located.

Several years ago, the landowners got together and made an offer to sell the land to the government for NT $850 million (about $2.5 Million USD), which is an outrageous amount of money for the 400 square meter plot of land.

Link: 恢復二林武德殿風采 地主開價8500萬 (自由時報)

Unable to fork over so much of the public’s funds for the land, the Martial Arts Hall’s designation as a 'protected historic site’ ensures that the land owners are also handcuffed, and are unable to do any sort of construction on the land, making the issue a contentious one for all parties involved.

The only option at this point is for the landowners to sell the property to the government, but with the government refusing to pay the asking price, both parties have decided to just wait the other out to see who concedes first.

The most dangerous aspect of this financial stalemate is that if the landowners eventually get tired of waiting for the government to pay up, they may just enlist the assistance of local gangs to have the buildings burnt to the ground, which is something that has sadly become far too common as of late when it comes to historic and protected properties.

For those of us who care about these heritage buildings, the only thing we can do is continue being patient. However, as I mentioned earlier, I’ve grown tired of seeing this article sitting in my blog queue.

With all of that being said, on May 18th, 2023, a ceremony was held in front of the Martial Arts Hall marking the start of the restoration of the building, with several local figures in attendance. It seems like the saga of the Erlin Martial Arts Hall’s status has been resolved, and work will soon get underway to have it opened up as a cultural park, and tourist destination within the downtown core of the historic village.

Link: 彰化文化資產容積轉移首例 二林武德殿等20年今動工整修 (lian he聯合新聞網)

I will make sure to keep up with any of the updates regarding the hall’s restoration, and when it’s opened, I’ll be sure to make my way down to visit.

Before I start explaining the history of the Martial Arts Hall, it’s important to note that I’ve streamlined the way I write about these spaces.

In this article, I’m only going to focus about the history and architectural design of this specific building - So, in order to keep it shorter, I’ve removed some of the original elements that focused on the ‘general purpose’ of these Martial Arts Halls - Even though it should be fairly obvious that this building was once a space for practicing Martial Arts, the original intent and the significance of these buildings requires a bit more reading to understand the role that they played in communities across Taiwan.

To better explain all of that, I’ve put together a general introduction to Taiwan’s Martial Arts Halls, detailing their purpose, their history and where you’re still able to find them today.

If you haven’t already, I highly recommend reading that article before continuing.

Link: Martial Arts Halls of Taiwan (臺灣的武德殿)

If you’re up to date with all of that, let’s just get into it!

Erlin Martial Arts Hall (二林武德殿)

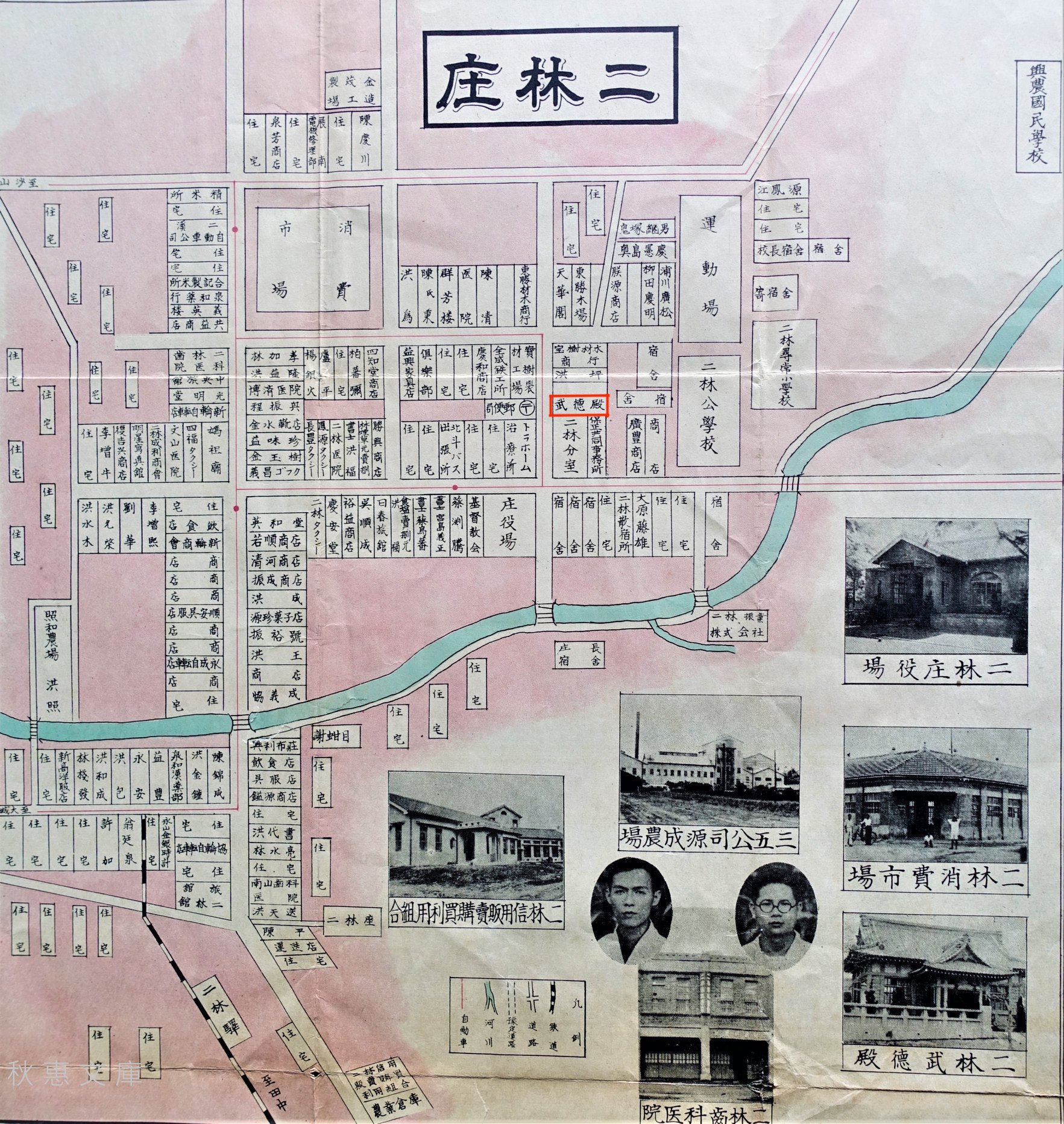

Unlike many of the other Martial Arts Halls that I have written about in the past, the Erlin branch is probably one of the few remaining Martial Arts Hall that requires an introduction to the town where it was constructed; Even for most locals, if you bring up the name ‘Erlin’ (二林), it’s unlikely that they’ll know where it is, and even more unlikely that they’ve ever been there. So, allow me start by explaining a bit of the geography of the area, which should shed a bit of light as to why a Martial Arts Hall was constructed there.

Known these days as Erlin Township (二林鎮), it’s the largest of Changhua County’s administrative districts, with an area of 92.8578 square kilometers. Erlin features a relatively small urban sprawl surrounded mostly by farmland, which is where the town’s economy has historically been focused. With massive rice, grape and dragonfruit fields, the area isn’t particularly known for its tourist crowds, so most people tend to pass through on their way to other destinations in the area.

Originally settled by the Tackay Tribe (二林社), a group of Taiwan’s Plains Indigenous peoples (平埔族), known as the Babuza (巴布薩族), the area is and always has been an important farming community throughout the history of human settlement on the island.

During the Dutch period, a considerable amount of trade between the Dutch and the Indigenous people took place between the two groups, resulting in the Dutch constructing berths for ships along the coast. However, after the expulsion of the Dutch by Koxinga’s forces, the situation remained more or less the same for the Babuza people, who maintained their control over the land from the late 1600s until 1895, as they continued their trade with the Han people.

All of that came to an end with the arrival of the Japanese, who quickly got to work at ensuring that they maintained complete control over the island, often with violent means of suppression, especially when it came to the indigenous people.

By the 1920s, ‘Jirin’ (二林街 / じりんがい), as it had become known to the Japanese was designated a township within Hokuto County (北斗郡 / ほくとぐん) within greater Taichu Prefecture (臺中州 / たいちゅうしゅう).

It was during this period that the Japanese had constructed numerous Sugar Plantations (糖廠) around the island, with the vast majority of them located within central and southern Taiwan where the temperate climate allowed for massive fields of sugar cane to be cultivated.

With over 3000 kilometers of sugar-railways across the island, Erlin just so happened to find itself located in one of the geographic hot-spots, and even though the factories were somewhat of a distance away, the town benefitted economically through the industry.

Much of Erlin’s urban development started during this period with the colonial government constructing a number of large administrative buildings, schools, hospitals and clinics, and modern markets within the ever-expanding downtown core of the town. In 1928, construction started on the Erlin Police Precinct (北斗郡警察課二林分室), located within the administrative district of the town, close to Erlin Public School (二林公校).

Located on a corner that shared an intersection with a hospital, the town hall and a long row of administrative housing, the police precinct would have been situated within what would have been considered the ‘Japanese’ area of town, with some separation from the local farming community.

In 1900 (明治33年), a few years after the Japanese took control of Taiwan, the first Martial Arts Halls on the island started being constructed, with the first branches in Taipei, Taichung and Tainan. Over the years, the ‘Taiwan Butokuden Branch of the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai’ (大日本武德會臺灣支部) slowly expanded across the island, but one of the key developments with regard to these buildings came in 1920 (大正9年), when the organization was given a directive (and more importantly funding) from the government to start construction on these buildings within each of Taiwan’s prefectures towns, villages and boroughs.

This resulted in the construction of about two hundred of them across the island (and in Penghu, too) between the 1920 and the early 1940s.

Of those two-hundred halls, thirty were constructed within Taichu Prefecture (臺中州), an area that spanned modern day Taichung City (臺中市) Changhua County (彰化縣) and Nantou County (南投縣). They consisted of two Prefectural Branches (支部), eleven town branches (支所), twelve borough branches (分會), two prison branches (刑務所) and three school branches (學校分會).

That being said, the area we know today as ‘Changhua County’ was only home to five branches: Lugang Martial Arts Hall (鹿港武德殿), Changhua Martial Arts Hall (彰化武德殿), Yuanlin Martial Arts Hall (員林武德殿), Beidou Martial Arts Hall (北斗武德殿) and Erlin Martial Arts Hall (二林武德殿). With the exception of the Martial Arts Hall in Lugang, which was constructed in 1911 (明治44年), the rest were constructed between 1930 (昭和5年) and 1933 (昭和8年).

However, one of the important things to remember is that even though a number of Martial Arts Halls were constructed across Taiwan during the early 1930s, not all of them were equal. As I noted above, the halls adhered to a hierarchical organizational structure which helped to determine their size, depending on their location and their function.

The Changhua Martial Arts Hall, for example was classified as a ‘city-level’ hall as it was constructed within Shoka (Changhua City / 彰化市 / しょうかし). A bit lower on the ladder would have been the Yuanlin and Beidou Halls, both of which were county-level (郡市級 / 支所), while the Erlin Martial Arts Hall would have found itself at the lowest level as a village-level branch (街庄級 / 分會).

Not only did these classifications help to determine the size of the buildings, but also the amount of money that would have been invested in their construction. According to historic records, the Changhua Martial Arts Hall was afforded a budget of ¥27,000, while the Erlin Martial Arts Hall had a budget of ¥7500. If we were to calculate these figures in the rates of the day, the construction costs would would be approximately ¥40.2 million ($290,000 US), and ¥11.1 million ($80,000 US) respectively.

Note: Calculating pre-war Japanese currency against today’s standards is somewhat of a difficult process given that most records only date back to the restructuring of the Japanese economy and inflation in the post-war period. To calculate the number above, I used the following formula: In 1901, corporate goods price index was 0.469 where it is currently 698.6, meaning that one yen in then is worth 1490 yen now. (217,000 x 1490 = 323,330,000)

Suffice to say, with a considerable amount of economic development taking place within Erlin in the early 1930s, the construction of the town’s Martial Arts Hall was a no-brainer for the local authorities. Construction on the building started in 1932 (昭和7年), at a time when the neighboring police precinct was still under construction. Located to the side of the police station, and close to the Erlin Public School, the hall, like many of its contemporaries was tactically located in a neighborhood where it could have the most effect. The building would serve as a training centre for the local police as well as providing instruction to the children as well.

Interestingly, despite both buildings being constructed almost simultaneously, the police station took a modernist approach to its architecture with an Art-Deco Baroque design. The Martial Arts Hall however, was a no-fuss traditional Japanese style building - and even though it is the smallest of all of the Martial Arts Halls that remains in Taiwan today, its architectural beauty is on par with the rest of them.

On August 4th, 1933 (昭和8年), the Jirin Budokuden (二林武德殿 / じりんぶとくでん), otherwise known as the ‘Erlin Martial Arts Hall’, officially opened for the instruction of Judo (柔道) and Kendo (劍道).

Initially the hall served as a space for the local police to hone their martial arts skills. However, as the Japanese became engaged in the Pacific War and the expansion of their empire, the colonial government in Taiwan instituted a policy of forced assimilation, known as kominka (皇民化運動), which forced the people of Taiwan to take Japanese names, speak only Japanese, and contribute to the empire through military service.

Taking effect in 1938 (昭和13年), the nearly two-hundred Martial Arts Halls across Taiwan played a major role in the assimilation process by promoting ‘Japanese Spirit’ (大和魂), ‘Martial Arts Spirit’ (尚武的精神) and ‘Patriotism’ (愛國的精神) and from then on, the scope of the instructors at the Martial Arts Hall expanded from simply training the police to providing classes to the general public and the nearby Public School as well. They were also tasked with planning speaking events that were meant to promote nationalist sentiment through the propaganda that was disseminated by the colonial government.

Nevertheless, the Second World War came to a conclusion less than a decade later, and as part of their surrender, the Japanese were forced to give up control of Taiwan (and any other territory gained through militarism).

Control of Taiwan was ambiguously awarded to the Republic of China, who sent a governor and military forces to Taiwan in 1945 (昭和20年) in order to set up shop. However, even though the Second World War had come to an end, the Chinese Civil War between the Nationalists and the Communists raged on. It was during this time that administrative control of Taiwan had become an authoritarian mess, resulting in an infamous event that would become known as the 228 Incident (二二八件事).

With the Communists establishing the People’s Republic of China in 1949, President Chiang Kai-Shek (蔣介石) was forced to flee to Taiwan with the remnants of his army, and anyone still loyal to the Republic of China.

The sudden influx of around two million foreign refugees created a housing crisis in Taiwan, and even though the Japanese had left all of their infrastructure intact, the first few years were a nightmare of governance.

Nevertheless, for the next half century, the Erlin Martial Arts Hall maintained its role as a Martial Arts training center with the Republic of China’s police taking over.

One of the areas that wasn’t entirely clear with regard to my research about the Martial Arts Hall is what happened when the Erlin Police Precinct was expanded in the early 1970s. What is clear is that when the expansion project took place, the lack of space in front of the hall caused some issues, so they ended up removing the ‘hafu porch’ that lead to the front door of the hall.

Digging a bit deeper, I discovered that the police station essentially expanded into an ‘L-shaped’ structure that completely blocked the Martial Arts Hall from view.

Even though the Martial Arts Hall remained as a training center for the police, it had essentially disappeared from the view of the general public for the next few decades after the expansion.

By 1999 (民國88年), the buildings utilized by the police in town were being reconstructed, so for a short time time, the Martial Arts Hall was used as an office space prior to their migration to a new building.

With the buildings that surrounded the Martial Arts Hall abandoned, it took a few years before the were demolished, thankfully, with careful consideration taken to preserve the condition of the hall, which had been recognized as a protected heritage property a few years earlier.

After being hidden from sight for almost four decades, the Martial Arts finally made its reappearance in 2008 (民國97年), but as mentioned earlier, its status remains a contentious one as it is a protected heritage property that just so happens to sit on land that is considered part private and part public.

This has understandably frustrated all of the parties involved, and is the main reason why the hall has yet to be restored, like so many of its contemporaries across the country. While I may be accused of a bit of bias on the subject, it really does come across as a missed opportunity for Erlin as the town has recently restored several other historic Japanese-era properties in the downtown area in addition to the promotion of its links to the historic sugar railway. These days there is more and more for tourists to see when the visit the area, so one would hope that at some point there will be a favorable solution to this stalemate.

Before I move onto the architectural design of the Martial Arts, I’m going to provide a brief timeline of events detailing the history of the hall.

Erlin Martial Arts Hall Timeline

1895 (明治28年) - The Japanese Colonial Era begins in Taiwan and the ‘Dai Nippon Butoku Kai was formed in Japan in order to instruct ordinary citizens in the various Japanese Martial Arts disciplines.

1900 (明治33年) - The first Martial Arts Halls start to appear in Taiwan with branches in Taipei, Taichung and Tainan.

1920 (大正9年) - A governmental directive is made to construct Martial Arts Halls in each of Taiwan’s prefectures, towns, villages and boroughs.

1920 (大正9年) - Due to the Colonial Government’s administrative redistricting plan, Erlin is upgraded into Jirin Town (二林街 / じりんがい), part of Hokuto County (北斗郡 / ほくとぐん) in Taichu Prefecture (臺中州 / たいちゅうしゅう).

1928 (昭和3年) - Construction on the Erlin Police Precinct (北斗郡警察課二林分室) officially starts with a budget of ¥17,000.

1932 (昭和7年) - Construction on the Erlin Martial Arts Hall with a budget of ¥7500 and is located next door to the police station.

1933 (昭和8年) - Construction on the hall is completed in July and the munafuda (棟札 / むなふだ) raising ceremony is held a month later on August 4th, marking the opening of the hall.

1936 (昭和11年) - The Colonial Government’s “Japanization” or ‘forced assimilation’ Kominka (皇民化運動) policy comes into effect in Taiwan.

1938 (昭和13年) - Jirin Public School’s Auditorium (二林公學校禮堂) is constructed and a number of ‘kominka’ events take place within, including Judo classes provided by the instructors from the Martial Arts Hall for the students of the school.

1945 (昭和20年) - The Second World War comes to a conclusion and Japan is forced to surrender control of Taiwan.

1949 (民國38年) - Chiang Kai-Shek and the government retreat to Taiwan and bring with them several million refugees displaced by the Chinese Civil War.

1972 (民國61年) - Due to the reconstruction of the Erlin Police Precinct, and a lack of space caused by a number of buildings constructed around the perimeter of the Martial Arts Hall, the traditional front porch in the front of the building is removed.

1976 (民國65年) - The ceiling within the building is reconstructed and modern lighting is installed within the interior.

1999 (民國88年) - Due to a lack of office space within the Erlin Police Precinct, the Martial Arts Hall starts being used as an administrative space for the local police.

2004 (民國93年) - The Martial Arts Hall is officially recognized as a Changhua County Protected Heritage Site (彰化縣歷史建築)

2007 (民國96年) - All of the buildings that were constructed around the Martial Arts Hall are carefully demolished, allowing the hall to be viewed by the general public for the first time in decades.

2023 (民國112年) - Restoration of the building is set to get underway with public funds allocated for the creation of a culture park with a focus on the Martial Arts Hall.

Architectural Design

Over the year or two, I’ve written about two of Taiwan’s other smaller Martial Arts Halls, the Taichung Martial Arts Hall (臺中刑務所演武場) and the Hsinchu Prison Martial Arts Hall (新竹少年刑務所演武場), which share a number of similarities with this hall with regard to its architectural design. Each of the three buildings were constructed in the early 1930s, and although two of them were used as extensions of the Japanese-era prison system, in a lot of ways the other two restored halls offer a glimpse into how the Erlin Martial Arts Hall might appear when it is restored. So, today I’ll start by describing their similarities and end with their subtle differences.

One of the defining characteristics of the early Showa-era, the architectural design of these Martial Arts Hall was at heart, traditionally Japanese, but there were also considered east-west fusion-style buildings (和洋混合風格). Constructed with a mixture of brick, wood and reinforced concrete, the hall was constructed during a period of the colonial era where the colonial government had learned through trial and error that any building constructed in Taiwan would have to be able to withstand earthquakes, typhoons and termites. This approach led to traditional Japanese-style buildings having to adapt to a bit of modernity in order to ensure their longevity.

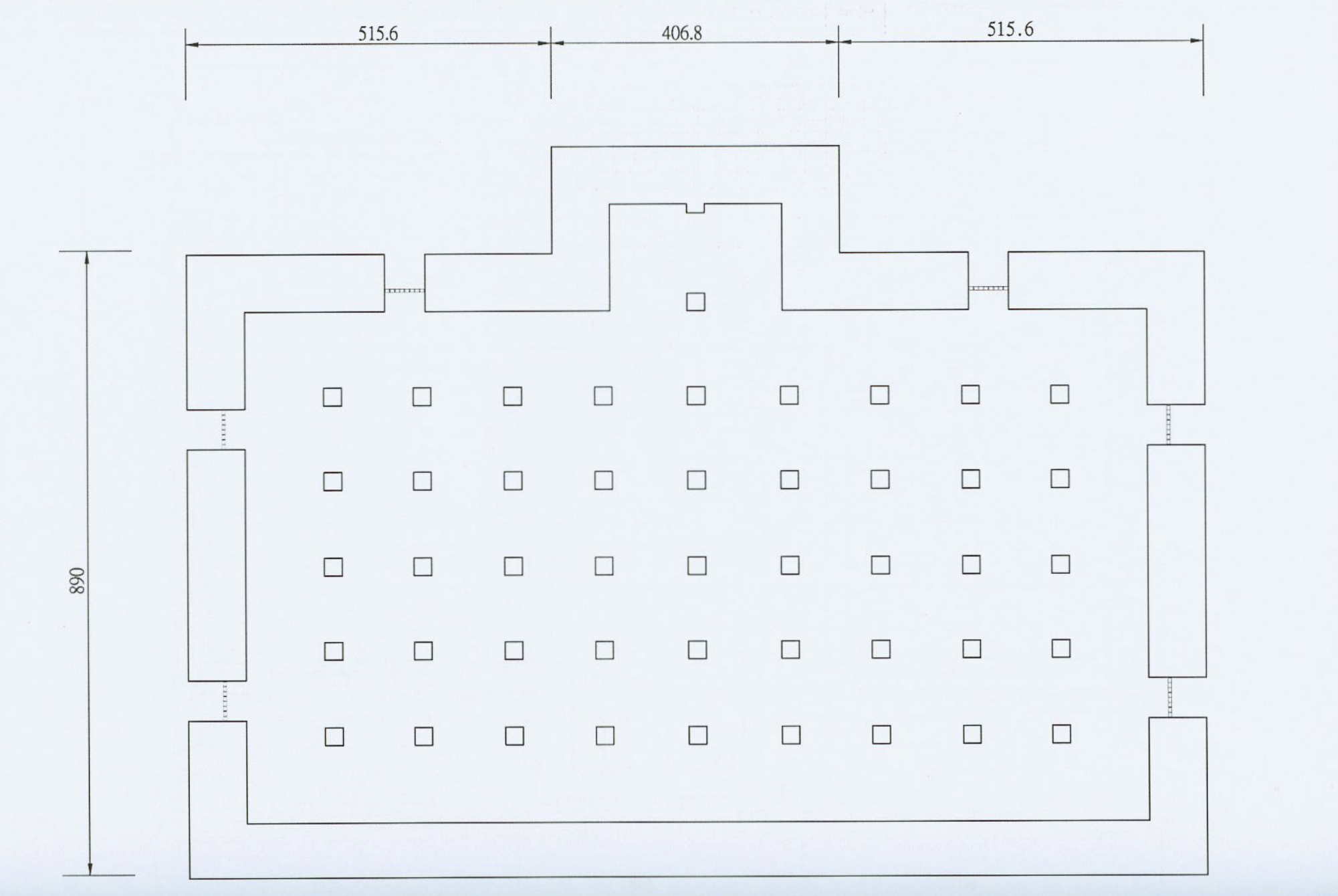

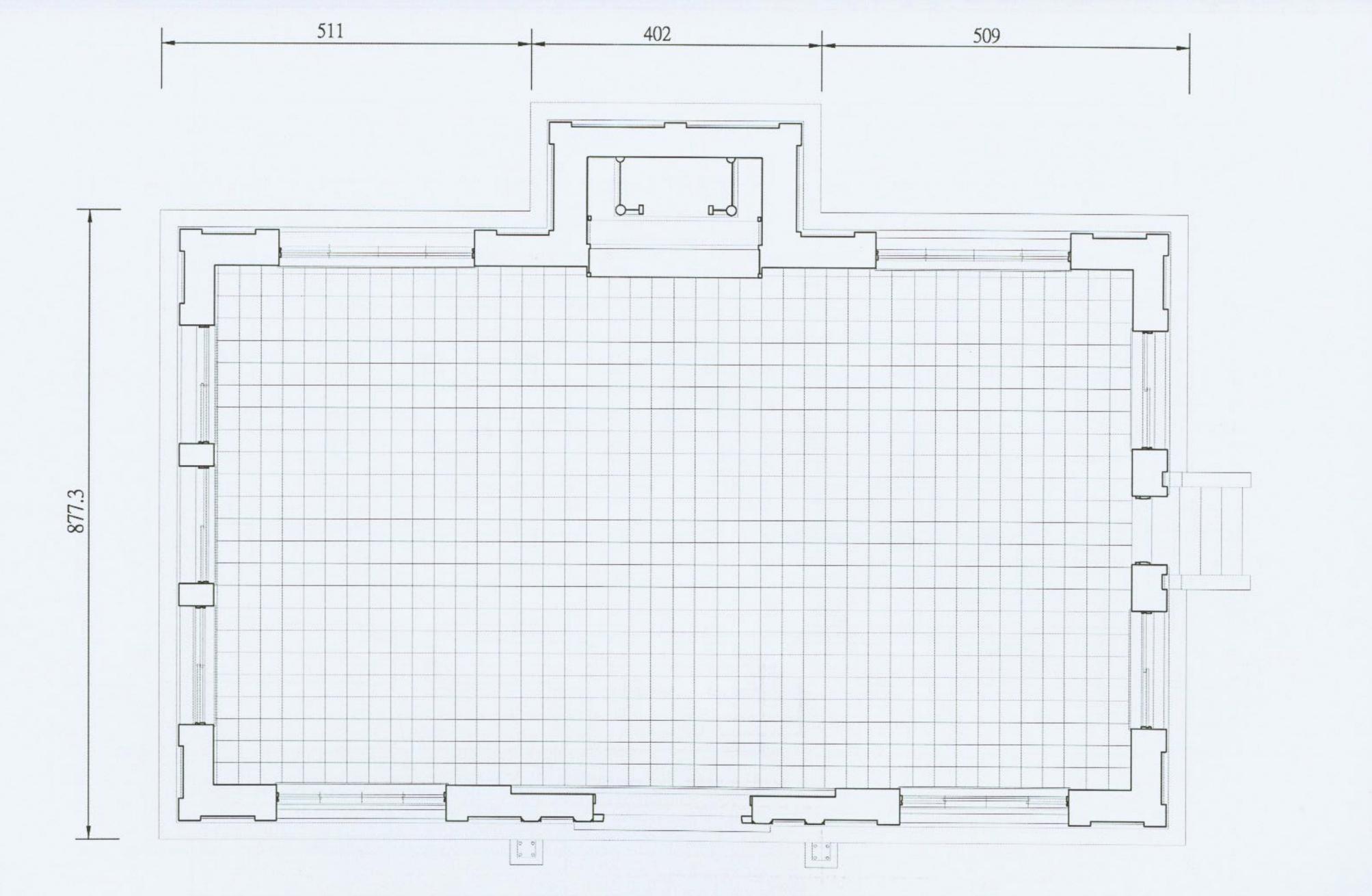

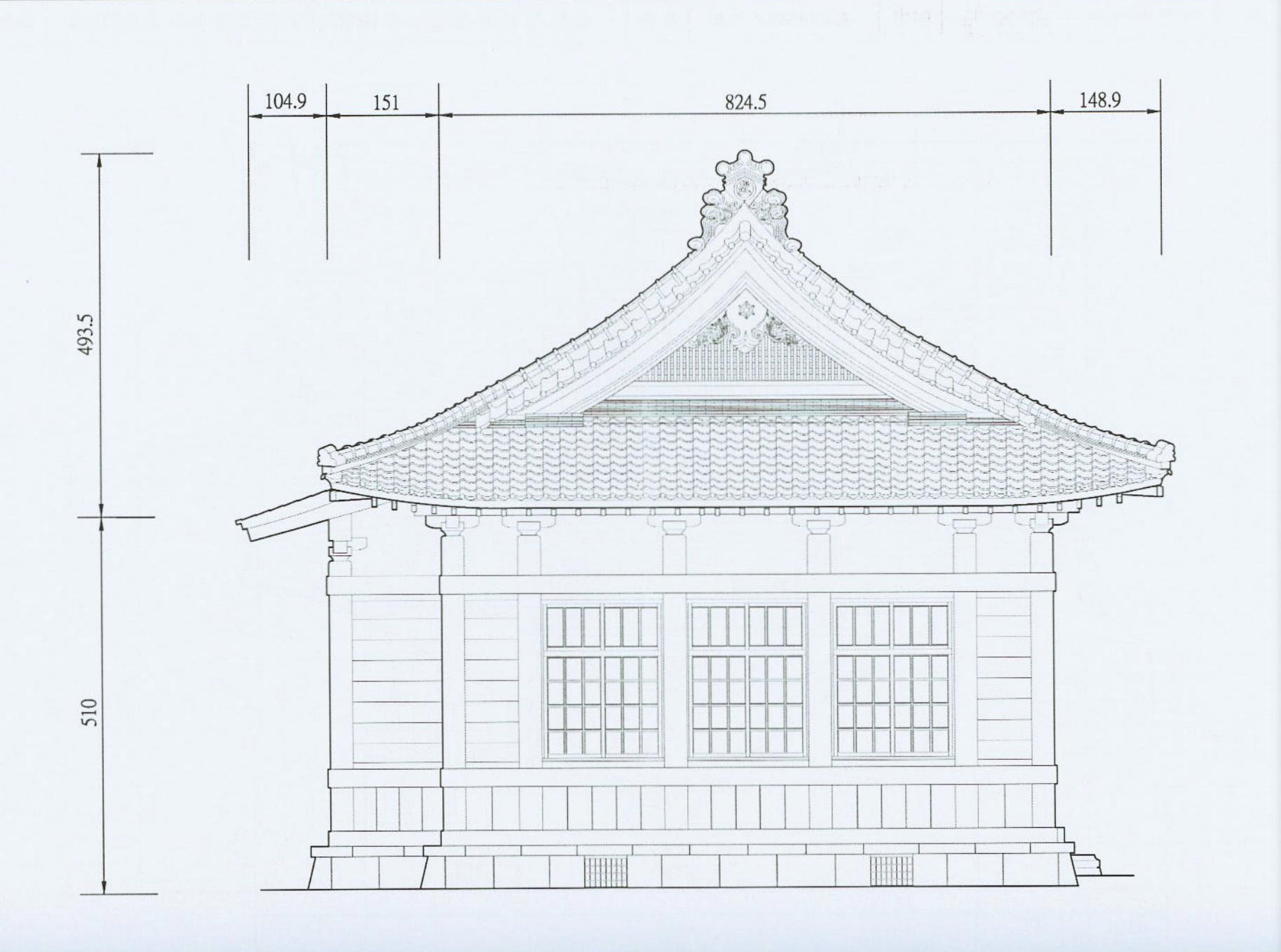

Nevertheless, keeping with tradition, the hall was designed using the irimoya-zukuri (入母屋造 / いりもやづくり) style of architectural design. I’m sure not a lot of you are very familiar with the term, so what that means is that the design features a variation of the ‘hip-and-gable’ roof. Similarly, the base of the building, known as the ‘moya’ (母屋) was constructed in a way that even though it is much smaller than the roof, it is easily able to support its massive weight.

Suffice to say, if you’ve ever seen a Japanese building with a roof that eclipses the size of the base by quite a bit, it’s very likely designed in the irimoya-style, or at least in one of its variations.

Similar to the two buildings mentioned above, the exterior of the building consists of washed stone, giving each of them their beige-like color. Likewise, given that these halls required bouncy floors, it was constructed with elevated footings that featured an intricate system of springs below the floor (彈簧地板), which allowed it to better absorb the shock of people constantly being thrown around while practicing Judo.

The elevated base featured a number of covered ventilation holes, which would have allowed people to climb under to repair any broken springs, while also keeping animals and termites out.

Despite being considerably smaller than the two halls mentioned above, another one of their design similarities is that the mixture of brick and reinforced concrete allowed for a number of large wooden-panel glass windows on every side of the building.

Even though access to the building has been blocked off, blue prints show that its design is essentially the same as every other Martial Arts Hall in Taiwan. The interior space was partitioned into two sides, with the west side reserved for Judo and the east side for Kendo.

Located in the center-rear of the room (directly facing the front door) you would have found a small space reserved for a shrine (神龕), and likely some decorative additions in addition to any trophies or awards won by members of the dojo.

Now, let’s talk about two of the most important design differences from this hall, and the two mentioned above. Both of which, I’m sure you’ll agree make this one considerably more beautiful than the other two.

First, let’s start out with the piece that’s missing, the front porch. Known in Japan as a ‘kurumayose porch’ (車寄 / くるまよせ) porch, it was essentially a beautifully designed covered-porch that opened up to the front door of the hall. This particular design feature is a popular style of design indicative of Japanese architecture dating back to the Heian Period (平安時代) from 794-1185. While these porches are more commonly associated with Japanese castles, temples, and shrines, its inclusion makes the building stand out a lot more thanks to its addition.

As is the case with this style of porch, it blended in really well with the roof, creating a beautiful 3D-like curvy design. Sadly, as I mentioned earlier, it was removed in 1972 to make way for the construction of a building in front of the hall. On the other hand, we’re actually quite fortunate (compared to the Hsinchu Prison Hall) in that there are both well-preserved blue prints and photos of this hall, which should make reconstructing the porch relatively easy when the time comes.

The most obvious design difference between the Erlin Martial Arts Hall and the other two is with the design of the roof - In this case, the roof is the more traditionally designed and aesthetically-pleasing of the three, giving the building a lot of character. Amazingly, after almost a century, and the demolition of the buildings that surrounded the hall in 2008, the roof remains in pretty good shape.

Expanding on my explanation of irimoya-design earlier, the iconic ‘hip-and-gable roof’ that comes with this design doesn’t necessarily mean that the roof of each building constructed in this style will always appear the same. Introduced to Japan in the sixth century, a number of variations have appeared over the years, making the specific shape of the ‘hip’ and the ‘gable’ important.

Link: Irimoya-zukuri (JAANUS) | East Asian Hip-and-Gable Roof (Wiki)

In this case we have a combination of kirizuma-zukuri (切妻造) and yosemune-zukuri (寄棟造), which is essentially a fusion of a ‘two-sided’ upper ‘hip’ section and a four-sided’ lower ‘gable’ section.

Looking directly from the front, the two-sided hip section of the roof, which is designed to look like the Chinese character “入,” or an ‘open book’, rises to its apex, and extends beyond the base of the building at the bottom. Supporting that part of the roof is the four-sided gable section below, which covers the base of the building and is where you’ll find the majority of the roof trusses that help to distribute the weight of the upper section and keep everything stabilized.

The shape of the roof however is not the only complicated part of its design. There are also a number of decorative elements that also play a very functional role. Using a diagram provided below, I’ll explain each of these important pieces and their purpose.

Hiragawara (平瓦 / ひらがわら) - A type of arc-shaped clay roofing tile.

Munagawara (棟瓦 / むながわらあ) - Ridge tiles used to cover the apex of the roof.

Onigawara (鬼瓦 / おにがわら) - Decorative roof tiles found at the ends of a main ridge.

Nokigawara (軒瓦 / のきがわら) - The roof tiles placed along the eaves lines.

Noshigawara (熨斗瓦 / のしがわら) - Thick rectangular tiles located under ridge tiles.

Sodegawara (袖瓦 / そでがわら) - Cylindrical sleeve tiles

Tsuma (妻 / つま) - The triangular-shaped parts of the gable on the roof under the ridge.

Hafu (破風板 / はふいた) - Bargeboards that lay flat against the ridge ends to finish the gable.

Link: 台灣日式建築的屋瓦 (空間母語文化藝術基金會)

Finally, two of the special features with regard to the roof and its decorative elements are the ‘onigawara’ end tiles, which are beautifully decorated with the Chinese character for ‘budo’ (武), which is a bit of a deviation from tradition, but makes the building more easily identifiable.

Likewise, within the triangular ‘tsuma’ (妻) on the east and west ends of the roof, you’ll find what is known as gegyo (懸魚 / げぎょ), which are simply decorative wooden boards in the shape of a ‘hanging fish’ that are used as charms against fire, similar to porcelain dragons you’ll find on the roofs of Taiwanese temples.

Unfortunately, with the restoration of the building yet to take place, the missing front porch, and the inability to gain access to the interior, it’s difficult to say much else with regard to the buildings architectural and interior design.

I might be beating a dead horse here, but I’m eagerly anticipating visiting the area again in the relatively near future to check out the fully restored building. Fortunately, as I mentioned earlier, the original blueprints and designs for the hall have been well-preserved, and there are also a number of historic photos of both the exterior and interior that will greatly assist the restoration team when the time comes. So I’m very much looking forward to the future of this hall, which should be a bright one!

Getting There

Address: No. 110, Section 5, Douyuan Rd, Erlin Township, Changhua County (彰化縣二林鎮斗苑路五段110號)

GPS: 23.899570, 120.369830

Erlin Village (二林鎮) is located in south-western Changhua County (彰化縣), close to the border with Yunlin County (雲林縣). Considered a relatively rural town, getting there through public transportation certainly won’t be as convenient as it would be for somewhere like Lugang (鹿港).

It is not impossible though, so if you don’t have access to your own method of transportation, you still have some options.

If you have your own method of transportation, I’m not going to spend too much time offering directions here. Simply input the address or the GPS coordinates provided above into your GPS or Google Maps, and you’ll have your route mapped out quite easily for you.

Public Transportation

While getting to Erlin might be a bit confusing for some, one of the best things about taking public transportation to the area is that the local bus station is located directly next door to the Martial Arts Hall.

There are, of course a number of options for getting to the area, but you’re probably going to have to use a combination of train and bus to get there more conveniently. Below, I’ll provide explanations for how to get to Erlin from each of the closest train stations.

Changhua Train Station (彰化車站)

From Changhua Train Station you’ll transfer to Yuanlin Bus (員林客運) bus #6713 or #6714. The shuttle bus doesn’t come that frequently, so you’ll want to be mindful of the time when you go.

From Changhua Station you also have the option of taking Changhua Bus #19 (彰化客運) directly to Erlin, but there are only ten departures per day, so, once again, you’ll want to keep track of the schedule, especially when you’re in Erlin so you won’t miss your bus back to wherever you’re headed.

Link: Yuanlin Bus #6713/6714 schedule | Changhua Bus #19 (彰化 - 二林)

Yuanlin Train Station (員林車站)

Located to the south of Changhua Train Station, your next option is to take the train to Yuanlin Train Station (員林車站) and from there taking Yuanlin Bus #6707 to Erlin. There are only a few shuttles every day, though, so this is probably not your best option.

Link: Yuanlin Bus #6707 (員林 - 二林)

Tianzhong Train Station (田中車站)

If you’re traveling north into Changhua, stopping at Tianzhong Train Station (田中車站) is one of your first options for getting to Erlin. From the station you’ll transfer to Yuanlin Bus (員林客運) bus #6709. However, the shuttle bus comes even less frequently than the option above, so you’ll want to be mindful of the time when you go.

Link: Yuanlin Bus #6709 (田中 - 二林)

Changhua High Speed Rail Station (彰化高鐵站)

Despite being named “Changhua” Station, the High Speed Rail station isn’t actually located within Changhua City, it’s located within Tianzhong Village (田中鎮). If you’re coming from a much further distance, the High Speed Rail is a pretty good option for getting to the area, but you’ll have to transfer from the HSR Station to a shuttle bus that takes you Tianzhong Train Station, and then you’ll follow the directions above and take Bus #6709.

Obviously, as it stands right now, I can't really recommend a trip all the way out to Erlin to see the Martial Arts Hall. There are of course a few other interesting tourist destinations in Erlin, but if you find yourself in Changhua, there are probably some better places for you to spend your time.

Hopefully though, at some point the ownership issues will be resolved and the government can start restoring the Hall to its original condition. When that time finally arrives, I'll make another trip down to check it out and will quickly update this article.

References

二林武德殿 (Wiki)

臺灣的武德殿 (Wiki)

武德會與武德殿 (陳信安)

二林武德殿 (國家文化資產網)

彰化-二林 武德殿 (Just a Balcony)

二林武德殿:日本武士精神的遺跡 (京築居)

失而复得的大唐建筑-台湾武德殿 (Willie Chen)

台灣武德殿發展之研究 (黃馨慧)

武德殿研究成果報告 (高雄市政府文化局)

二林武德殿調查研究暨修復計畫 (黃俊銘 / 中原大學)